There’s been a lot of interest lately in the question of whether we need a socialist party in the US. Perhaps to put this in a way people might ask it: Do we need a socialist party in our time, and, if so, what would it look like? In one sense, it’s a surprising question. We have a socialist party in the US! In fact, we have lots of them.

A Socialist Party?

How many? Let’s find out. Here’s a list of socialist parties in the US, at least parties big enough to have both a wikipedia entry and a website.

African People’s Socialist Party

All-African People’s Revolutionary Party

American Party of Labor

Bread and Roses

Communist Party USA

Communist Party USA (Provisional)

Freedom Road Socialist Organization

Freedom Socialist Party

New Afrikan Black Panther Party

Party for Socialism and Liberation

Peace and Freedom Party

Progressive Labor Party

Revolutionary Communist Party, USA

Socialist Action

Socialist Alternative

Socialist Equality Party

Socialist Labor Party of America

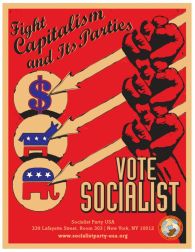

Socialist Party USA

Socialist Workers Party

World Socialist Party of the United States

Workers World Party

What a lot of socialist parties we have! And you think we need another one? OK, I get it. Whatever it is you’re calling for, it’s not more of that. I suspect we’ve got enough of those kinds of parties. And while some of these groups do good work on the ground, many are just splinter groups from others. Some are probably just a couple people in a basement. Splinter groups divide for arcane doctrinal reasons at best and petty personalities and egos at worst. Maybe what we need is a different kind of socialist party. Or so proponents of the idea seem to think.

I’ll bite. Let’s talk about what a 21st century socialist party should be.

A Party Surrogate?

I read an article recently in Catalyst called ‘A Socialist Party in Our Time?‘. Jared Abbott and Dustin Guastella argue we need a party surrogate. Here’s the basic idea. Election law in the US is complicated and drawn across all 50 states and hundreds of local jurisdictions. The mishmash of laws and structures makes it nearly impossible for a third party movement to build a sustainable base and gain victories. The few times it’s happened in US history tended to be more than a century ago, when the law wasn’t quite as onerous, and during periods of major social upheaval.

Furthermore, the internal structure of the Democratic Party makes it difficult to take power from the inside. Democratic Party members don’t directly elect party leaders like Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer in the way that, say, UK Labour Party members directly elected Jeremy Corbyn. Local party structures are more open to outsiders, but they’re relatively powerless. These things complicate working class efforts to push the Democratic Party in a more positive direction via the use of democratic processes.

The solution? A party surrogate! Abbott and Guastella conclude from these difficulties that a party surrogate is the best way to accomplish electoral change.

What’s a Party Surrogate?

A party surrogate is a mass member organization that depends on working class small donors. It’s not a union. Nor is it solely a political party, but it runs candidates both within Democratic primaries and as independents in other cases. It focuses on elections, but it also supports mass movements, strikes, issue-based campaigns, et al. It provides financial support to candidates taking on the Democratic Party establishment, and it holds candidates accountable to socialist priorities through its mass member base. Eventually, the party surrogate replaces the Democratic Party or turns it into something socialists can support.

That’s the basic idea, anyway. Are there more details? Sure, and there are quite a few. Check out the Abbott and Guastella article to read more about those. They go into the details of what’s wrong with the Democratic Party, operationally, why it’s difficult to take power through it, and what the party surrogate can do to help its candidates and hold them accountable.

Problems with the Party Surrogate Model

I think we need to be more creative about how we think about a socialist party on the US left. From narrow workerist organizations to Maoist splinter groups to just becoming Democrats and hoping for the best, the US left has created a graveyard of failed electoral organizing strategies. And so, I liked the party surrogate models for proposing an idea with at least some freshness.

In that spirit, I’ll lay out some problems and issues with the model that I mean to be constructive rather than destructive. I think there are some good idea we can use from Abbott and Guastella.

The Electoralist Assumption

The party surrogate is, first and foremost, an electoral group. Abbott and Guastella repeatedly claim that power is won electorally, but this is much more assumption than considered view. And even if power is won electorally, that doesn’t mean elections are a first step. Rather than immediately jumping into electoral politics and structuring mass movements around candidates, we might build mass movements, win victories, and structure candidates and elections around those movements.

Dropping the electoral first attitude and switching to a movement first attitude would also go some distance toward solving the key problem of politician accountability. There’s a lot we can do right now in terms of mass mobilization, especially via email and text message, but we’re a long way away from the point where we can collectively hold candidates accountable. Consider, for example, Elizabeth Warren’s decision to abandon Medicare for All as a core priority. The left-leaning groups endorsing her, like the Working Families Party (which I’ll discuss below), have done nothing to hold her accountable. In fact, the WFP continues pretending it didn’t happen. Thus, even sympathetic groups haven’t solved this key electoral problem.

The Party Surrogate’s Base

Who’s going to join the party surrogate? Leftist intellectuals or liberal bubble dwellers? Or union leaders? Abbott and Guastella say it’s low wage workers. I’ve discussed this group in some detail in the past, but the key point here is that this is a group with some overlap with the working class, but at other times distinct issues. To some extent, that’s fine. It helps us avoid organizing around only the most well-off members of the working class.

There are a couple of complications, though. First, some members of the low wage sector are actually pretty well positioned in terms of class. Consider, for example, struggling small business owners or small-time landlords. But, more importantly, there are troubling political trends and tendencies among many members of the ‘precariat’. Without the support of mass organizations like tenants unions, labor unions, and community groups, many low wage workers are susceptible to snake oil salesmen like Andrew Yang and bad idea like UBI.

As a result, low wage workers are an important part of any socialist party, but they probably can’t be the sole base of a party. If we’re thinking about who to organize, we need a broader base than this.

Movementism/Electoralism Dichotomy

A key part of Abbott and Guastella’s assumption is that they lump any alternative to electoralism into the boxes of ‘movementism’ or cult/sectarian organizations. The term ‘movementism‘ has a contested history on the left, to put it mildly. But as they’re using it, it basically means people who join one group after another without having any kind of central political goal or strategy to reach it. They take Occupy Wall Street as a key example of a movement where a lot of people joined and showed enthusiasm, but where there was no sense of where we’re going or how to get there.

I’m not going to respond by defending what Abbott and Guastella criticize, at least not completely. But I think they’re too dismissive of the insights of movements like OWS. And I think they’re wrong to posit electoralism as the only way of filling out a goal and strategy. Many groups that people think are directionless actually do have direction, but that direction is toward things that don’t come to mind for many people. Sometimes it’s fighting capital locally, through things like anti-eviction or anti-wage theft campaigns. Sometimes it’s fighting capital via a less obviously direct route, such as anti-ICE or anti-police brutality campaigns.

Models for a Socialist Party

Since this all gets a bit abstract, I want to run through some examples of what a US socialist party might look like. I’ll start with one I think Abbott and Guastella very much overlook in their article.

Working Families Party

Abbott and Guastella discuss examples, several of which are US-based groups. But they don’t have anything to say about the Working Families Party, which surprised me.

Why?

The WFP is the closest thing we have to what they advocate. It’s an organization of working class, low wage, and intellectual members, organized as a coalition of unions, non-profits, and advocacy groups. It charges $10/month for members, so it’s a group funded directly by small donors. How does the WFP operate? More or less exactly how a party surrogate is supposed to operate on the Abbott and Guastella model. They run candidates through fusion tickets, run candidates on their own, and endorse Democrats where applicable. They pursue the regional strategy Abbott and Guastella advocate, focusing on states like New York that make it easier for party surrogates to operate.

The problem? It’s not a particularly successful model, at least not so far. The WFP has improved as of late, diversifying its leadership base and improving its endorsements. But the group has a long history of endorsing bad Democrats in the pursuit of power. And its history is really more one of an advocacy and email mobilization group than a group organizing to push for working class power.

Among other poor decisions, the WFP endorsed Joe Crowley against Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, even though several groups to its political right endorsed AOC. And it endorsed Andrew Cuomo for Governor, a decision he repaid by trying to severely damage the WFP. In the 2020 presidential race, it endorsed Elizabeth Warren over Bernie Sanders. While not as egregious as the others, it’s also clearly the wrong choice. The underlying problem with the WFP and WFP-like groups is that there are powerful incentives to do things like this in order to curry favor with the Democratic Party.

Labor Party

Some people don’t know we had a Labor Party in the US! I mean, we’ve had several. But I’m talking about the Labor Party founded in 1996. There’s something of a vague consensus on the US left that this was a good idea that wasn’t carried out well. I’ll dissent from that and argue that it was probably a bad idea and turned out about as expected. On this topic, I’d highly recommend reading Jacobin’s 2015 interview with Mark Dudzic.

Dudzic argues pretty directly that the Labor Party was too narrowly focused on elections and didn’t center mass movements and organizing in the ways it should’ve. Since this time, much of the mainstream labor movement has gone back to lobbying the Democratic Party or trying to browbeat it into doing what labor wants. I’d add to this that its base was far too narrow. And narrow in multiple respects. It was centered on particular sectors of the existing union movement, the people already organized. It didn’t have a solid base among the unemployed, the underemployed, low wage workers outside of the union movement, tenants, identity-based groups, or anyone else who ought to be part of a broad coalition of those hit by capitalism.

Farmer-Labor Party

On this note, I’ll briefly mention the Farmer-Labor Party. Not as a national model, because that’s not what it was. It was a party based in the state of Minnesota. And it united two different groups, agricultural workers and industrial workers, who faced similar issues at the end of World War I.

This model worked in a particular time and place. And it united together two typically separate groups around a set of concerns that arose at a particular point in US economic development. As an example of coalition-building, it works really nicely. The problem, of course, is that the coalition behind a socialist party must be much broader than this. But we can learn lessons from Farmer-Labor.

An Anti-Capital Party as Socialist Party?

Finally, I’ll leave you with my own thoughts on what a socialist party should look like. Some of those thoughts shouldn’t be surprising. I’ve dispersed them throughout this post. And so, I think a socialist party should be a mass movement organization first and an electoral organization only carefully and secondarily. I think we should focus a socialist party very closely on organizing people through one-on-one conversations and movements against local and regional manifestations of capital. In that, we have a lot to learn from the book No Shortcuts by Jane McAlevey.

But, finally, the base of a socialist party is a coalition of many different groups hit hard by capital. Working class people? Yes. Low wage workers? Also yes. The unemployed and dispossessed? And…yes. Also, tenants, immigrants, black and Latinx people even in the middle classes who face the worst of racism and xenophobia, et al.