I get a feeling of uncanny accuracy when I read In the Dream House. Not because I’ve ever been in an abusive relationship. I haven’t, and I hope things stay that way forever. It’s because the road – both geographical and description of place – looks so familiar and yet so far away.

Carmen Maria Machado wrote the book, and she wrote it about her relationship with an abuser who’s part of writing communities in Iowa City. Their relationship spans the U.S., but it mostly spans the distance between Iowa City, Iowa and Bloomington, Indiana.

I live in Iowa City, and I used to live in Bloomington. 6 years of the former followed by 12 years – and counting! – of the latter. Setting aside a year in Minneapolis, I’ve lived half my life in these two places.

People and Places

I recognize the characters in the book. Sometimes literally. Machado draws her central support network from two housemates I’ve met in person. They’re good people.

Machado never names her abuser in the book, but I know who she is. Probably anyone connected to Iowa City’s cultural scene who’s read the book knows who she is. We’ve spoken a few times in passing, but we’ve never been friends or even acquaintances. I’ve never met Machado herself, but she’s a familiar Iowa City character: moved here for a reason, joined various intellectual social networks, achieved her purpose, and then moved away.

Everything else about the book is familiar to me. The descriptions of Iowa City as a place: its frat bros, its writers, its networks of support and denial. The descriptions of Bloomington as a place: its sharp division between town and gown, its status as oasis in the middle of Republican Indiana, its disjointed politics.

More than anything, I recognized the road between Iowa City and Bloomington. Machado travels the road again and again – crossing Illinois, arriving in the dream house, heading back again. The desolate stretches stand out, phantom gas stations announced on highway signs but never quite within reach.

Belief and Support

When people talk about sexual assault in 2020, they often ask us to ‘believe women.’ The entire discussion takes place under a debate around belief and the reliability of testimony: Should we believe this account? Is this person’s testimony credible? And so on.

These questions aren’t unimportant. To say to a person that you believe them can be a powerful form of support. But I want to nudge readers a bit from the epistemological turn and ask them instead to focus on the notion of ‘support.’

I believe Machado. At a minimum, I think she’s fully sincere and that she suffered harms. It’s in the nature of both memoir and memory that the story’s told by a full person with a context. If Machado’s abuser wrote a truthful version of the story from her perspective, I’m sure it’d differ in some particulars. But I think the basic account would be the same.

I always start from a place of giving credence to someone reporting they were abused, but those reports aren’t infallible. It’s a presumption of truth, not a final judgment. Some of what pushed me from presumption to judgment – to a settled position that Machado is right – was her clear and truthful description of Iowa City, Bloomington, and the journey between them.

The point? Belief can be a form of support, but it’s not the only form. It’s usually not even the most important one.

It Follows

When I watched the horror film It Follows, my first thought was it showed a form of support for victims that acted very independently from belief. Haven’t seen it? Here’s the idea: an evil spirit follows and tries to kill a person. That person can only dodge the spirit by having sex with someone and passing it along. But a person can never quite shake the spirit. If it kills its target, it moves along to the previous person. And so, people have to keep having sex to continue passing it along. They hope the next person keeps passing so the spirit never makes it back to them.

It’s an obvious HIV/AIDS allegory, but let’s set that aside. Instead, let’s look at it from the perspective of a friend of the victim. Your friend reports this story, and asks for your support.

Would you believe her? Surely not, at least not literally. There’s no such thing as evil spirits that chase and kill people. But the friend still needs support. I hope I’d be a good enough friend to provide that support.

In It Follows, the belief question is secondary to the support question. The main character’s friends don’t really believe her at first, but they unfailingly support her anyway. They stay with her. They help get her to safety. And, eventually, after they see the spirit is real, they help her defeat it. Maybe. It’s a horror film, and so the film leaves open the possibility the spirit isn’t totally gone.

In the Dream House

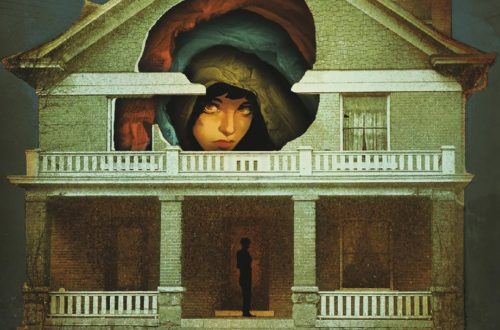

Much of the story takes place in the dream house, as the title suggests. In the dream house in Bloomington, that is. Machado’s abuser lived in Bloomington for much of the relationship, while Machado herself lived in Iowa City. Many facets and features are in the dream house, but one of them is that it’s the abuser’s house.

I started by describing the experience of reading Machado’s book as an uncanny one. Uncanny because while it rang true, it’s noticeably different from my own experiences in relationships and in Bloomington and Iowa City. I’ve seen plenty of relationships and houses in Iowa City, many that look, on the surface, like the ones Machado reports. But it’s been an overwhelmingly happy experience for me.

I think Iowa City is the best place to live, and Bloomington might be the second best place, and so it’s heartbreaking to see someone experience these places as ones that carry so much pain. And both my partner and I carry a deep appreciation for the home – especially the older home – as a place of comfort and joy. To see the home as a place of fear is similarly heartbreaking.