It’s one thing to say we need a social democratic party – or socialist party – in the U.S. It’s quite another to say who its members will be.

But plenty of leftists think they’ve got it down. The story goes something like this. First, we organize around a social democratic platform: Medicare for All, a $15-20/hour minimum wage, free college and cancellation of student loan debt, housing for all, a Green New Deal, et al. Then, we use the strength and momentum from the social democratic program to push for more. We directly challenge the basic capitalist structure of ownership and control.

Sure, the plan has its problems and pitfalls. For example, do we organize within or outside of the Democratic Party? But most leftists endorse it in its broad outlines. For a couple of recent examples among many, see Bhaskar Sunkara’s book The Socialist Manifesto and Nathan J. Robinson’s book Why You Should Be a Socialist.

I do think the plan’s proponents underestimate the difficulty of finding a constituency for a social democratic party. They heavily rely on appeals to the materials interests of the U.S. working class, but those interests – and the size of the working class to which they appeal – are shakier than they think.

A Dilemma for a U.S. Social Democratic Party

Let’s think about this in the form of a dilemma. The U.S. left wants to build a mass member based social democratic party. And it wants one that’s relevant and competitive at the national level. To do so, the party can base its mass membership in the working class or in other groups.

But in the current political environment, the left can’t have both a relevant and competitive social democratic party and a working class base. If they choose a working class base, their party won’t be large enough to be relevant and competitive. And if they choose a base grounded in other groups – white collar workers, young professionals, et al. – the party won’t be social democratic.

We’ll look at the two horns of the dilemma in turn.

A Working Class Base?

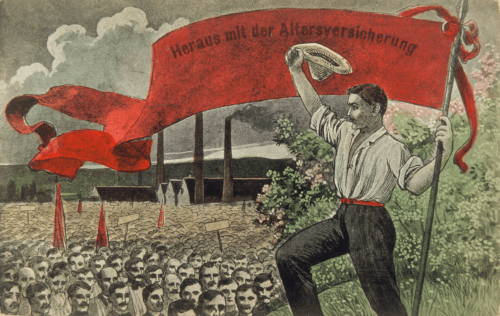

In a recent article in Catalyst, Loren Balhorn writes about the history of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). The SPD’s membership declined at a particular historical junction. As it transitioned from a working class party to a white collar party, those numbers declined. Intuitively this suggests all it needs to do to regain its strength is to re-situate itself as a working class party. Right?

Wrong. The transition was as much effect as it was cause, as Balhorn points out. The SPD’s working class base declined in both number and financial and political clout as it was decimated by neoliberal capitalism. It could no longer sustain a major national political party, and the SPD reacted accordingly.

The same story repeats in places like the UK. The decline of the Labour Party’s traditional base of industrial workers led it to move to white collar workers and young professionals. And in the U.S., the Democratic Party – while never a social democratic party and never a predominantly working class one – certainly had more of a working class member base in the 1960s and 1970s than it does now.

Too Small

In the current political environment, there aren’t enough politicized working class people to make up a major national party. The American workplace itself is de-politicized and rife with corporate ideology – from your standard ‘bootstrap’ happy horseshit to the more formal, pseudo-intellectual fare like Lean production or Agile. The party would be too small.

The deeper question is whether there are enough working class people of any kind – whether politicized or de-politicized. Perhaps there’s a hidden base of working class people ready to be politicized by current events or an educational program? I’ll return to this question later. For now, I’ll point out that yes – there are lots of people working precarious jobs not organized by a union contract. And there are white collar workers with titles like ‘manager’ or even ‘director’ who are really just rank-and-file workers being paid, in part, in inflated job title.

But putting together a coalition like that one requires hard work and organizing. The ‘political party’ part probably comes near the end of the timeline, not the beginning.

Bernie Sanders 2020

I’ll eventually have more to say about the Sanders 2020 campaign and why it didn’t work. But for now, I’ll note that the Sanders campaign was premised on taking this horn of the dilemma. He wanted to put together a broad base of young people and working class voters, especially Latinx working class voters.

Sanders gave it a great shot, but it didn’t work. His campaign showed the need for political education and movement building first, and elections later.

A Non-Working Class Base?

And then there’s the other horn of the dilemma: finding a different base. We know it’s possible for centrist or center-left coalitions to win elections on a base of white collar workers and young professionals. It happens all the time: Gerhard Schröder in Germany, but also Antti Rinne in Finland, Stefan Löfven in Sweden, et al. Even in the U.S., Barack Obama rode a similar coalition to victory in 2008 under the banner of ‘Hope and Change.’

But none of these governments were social democratic ones. While some of them made liberal gains in social policy, all endorsed and deepened neoliberal capitalism. From the perspective of the left, each one failed.

The 2020 Elizabeth Warren campaign pushed this route to its limit. She did so analogously to how the Bernie Sanders campaign pushed the other route to its limit. Warren ran a progressive campaign with a base of college educated people in white collar employment, often quite lucrative employment. But she encountered two problems. One, she failed to gain traction outside of this narrow base. And two, her policies weren’t social democratic, either. She – probably in part because of her non-working class base – pushed at the boundaries of progressivism without crossing over into the territory staked out by the left as its electoral ground.

What is to Be Done?

Let’s return to the large groups of Americans working in rank-and-file employment but who aren’t typically considered ‘working class’: part-time educational workers, baristas, rideshare employees, other gig workers, non-profit workers and lower ranking ‘managers,’ health care workers, et al.

These kind of workers never comprised the base of a working class political party. Most aren’t unionized. Many don’t vote at all. Most don’t organize on or off the job. The left can’t just release a platform – or candidate, or party – in front of them and expect them to sign on. It’ll take a lot of organizing and movement building to put such a social democratic party together.

And even that – by itself – won’t be enough. Addressing the concerns of these workers requires integrating into the conversation different cultural backgrounds and the fact that the workers are disproportionately black or Latinx. They’re mostly women. And they’re mostly tenants rather than homeowners. And they’re still not an actual electoral majority.

Putting all these things together requires detailed, complicated conversations about all aspects of life. It requires a social democratic vision that’s actively anti-racist, anti-sexist, pro-tenant, et al. And those features must be strong enough – and accessible enough to people not steeped in social justice jargon – that we can use it to build practical alliances with others: white collar progressives sympathetic with our goals, middle income black and Latinx people, et al.

This kind of work not only goes beyond one party or one campaign, it doesn’t come from above.