We’re well into spring these days. What are you reading? My list this month is a nice eclectic mix of sci-fi, historical fiction, political science, and hot topics in politics.

I hope you enjoy!

Norman X. Finkelstein – I’ll Burn That Bridge When I Get To It

It’s fair to call this book heavy – both in physical size and topics. What holds it together is Finkelstein’s wide-ranging condemnation of identity politics, inclusive of both the right and the left.

As always, the fight over what the term ‘identity politics’ picks out is half the battle. For Finkelstein, movements practice identity politics when they fight both amongst themselves over how to define the core identity (e.g., ‘black,’ ‘woman,’ and so on) and also with other groups over representation in the world of politics and economics.

As far as it goes, I agree with Finkelstein that that sort of identity politics isn’t so great. But, as I’m sure readers know, there are better kinds of identity politics.

Much of the book comes at the reader in the form of takedown after takedown. He goes after figures such as Robin DiAngelo and Ibram X. Kendi with aplomb, and he’s correct about their work far more often than he’s incorrect. Any reader who accepts those authors at face value should take a look at his critiques.

That said, other remarks come off as weird or unfair. And some of this distinctions, e.g., Obama as playing identity politics but Bill Clinton as not doing so, are particularly egregious.

Finkelstein himself, of course, was himself a major victim of unfair ‘cancel culture.’ Phony charges of antisemitism in his case. And he provides a thorough and thoughtful discussion of academic freedom in the second half of the book. I might not agree with every point he makes, but he makes his points carefully and in a well reasoned manner.

In short, the book is insightful at times and cringe at others. And it desperately needs an editor. Removing unnecessary block quotes alone could trim 75-100 pages from this book.

Marc J. Hetherington and Jonathan D. Weiler – Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics

A couple of political scientists set out in 2009 to use the concept of authoritarianism to explain the polarization found in U.S. politics in the 1990s and early 2000s. A decade and a half later, this project will seem either prescient or quaint to most readers.

Hetherington and Weiler show a strong relationship between authoritarianism and certain partisan political debates of the early 2000s (e.g., same-sex marriage). I suspect these relationships still hold today. And, perhaps, even more so now than then.

But a key problem with this book is that, first, ‘authoritarianism’ is a squishy idea, at best. The authors themselves do acknowledge this, of course. But I suspect it’s so squishy that it fails to hold together in a meaningful way. The authors don’t have a good story for why ‘authoritarianism’ persisted for decades as a common (majority, even!) trait in a society that itself isn’t authoritarian by a comparable definition.

In short, I think the authors use ‘authoritarian’ to describe something we often can’t pry apart from ‘traditionalism.’ And while there’s still something interesting about partisan polarization along a traditionalism axis, the main framework the authors use isn’t really doing much explanatory work. Their thesis reduces, I think, to the claim that the U.S. is a traditionalist society with a growing body of non-traditionalists. This has sparked a backlash among traditionalists, who have concentrated in the Republican Party.

Indeed. That sounds familiar from the 2016-2024 years. But, again, I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader whether that thesis is prescient or quaint.

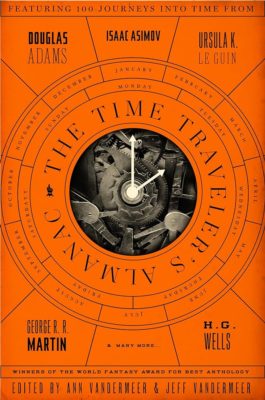

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer (eds.) – The Time Traveler’s Almanac

So, the VenderMeers deliver a collection of time travel stories. A huge collection of stories, clocking in at over 900 pages.

To help the reader, they carve the broader landscape of stores into four types. These types range from experiments to politics to paradoxes to messages sent into the past or the future. And while the focus is obviously on sci-fi stories, a few delve into fantasy territory. The stories also cover a time period stretching from the late 19th century to today.

In good news, I found in this collection lots of stories worth reading. And the editors do a nice job bringing together diverse perspectives, both in terms of the authors and kinds of stories represented. I discovered a few new authors, and I read a story from my favorite sci-fi author that I hadn’t previously read.

In less exciting news, I though the collection was simply too big. A few stories don’t even really fit into the ‘time travel category.’ And, overall, I though the VanderMeers could’ve trimmed the collection to about 700 pages without losing much of note.

On the whole, readers interested in time travel can find lots of great reads here. But they might want to pick and choose a bit among the stories.

Gore Vidal – Lincoln/1876/Empire

I’ve written about Vidal’s Narratives of Empire series previously. And for a few months, I’ve been making my way through the middle novels. In terms of chronology, these books cover the Civil War years through the height of the formal U.S. Empire in the early 20th century.

Lincoln serves as a contrast to 1876 and Empire in some ways, though the latter novels build on the former in others. None of the books feature a main character, though Charles Schuyler (from Burr) moonlights as one in 1876. And John Hay nearly plays the role, in a mirroring way, as young man in Lincoln and elder statesman in Empire.

As for his style, Vidal portrays larger than life politicians somewhat distantly. Nowhere does he do this more effectively than the portrayal of Abraham Lincoln himself, who, perhaps more than anyone, embodies the clever realpolitik Vidal attributes to the greatest U.S. statesmen.

This comes out in each of the novels. In Lincoln, most obviously, in Honest Abe’s banter and wit that cover over hardboiled politics like no other. In 1876, the story centers on a (twice) stolen election – once by the exclusion of black voters in the South and a second time by the Republican opponents of the anti-Reconstruction whites – that exposes the ironic anti-democratic realities of the U.S. on its centennial. And in Empire, it all comes together as the U.S. transitions into an Empire with the 1898 occupation of Cuba and the Philippines.

Once again, as with Burr, I can’t speak to the historical accuracy of anything in Vidal’s fictional account of U.S. history. But he tells the story in a way that helps the reader see deeper truths.

While I’m going to take a little break after the fourth novel, I have to say I’m loving the series.