Hello everyone, and welcome to the second reading list of 2025! Deep in the Iowa winter, I’m staying warm with some books. And I hope you are, too.

I wrote last month about philosophical counseling, and I’m doing a bit of themed reading around that. Beyond this, I’ve found some interesting politics and fiction.

How about you?

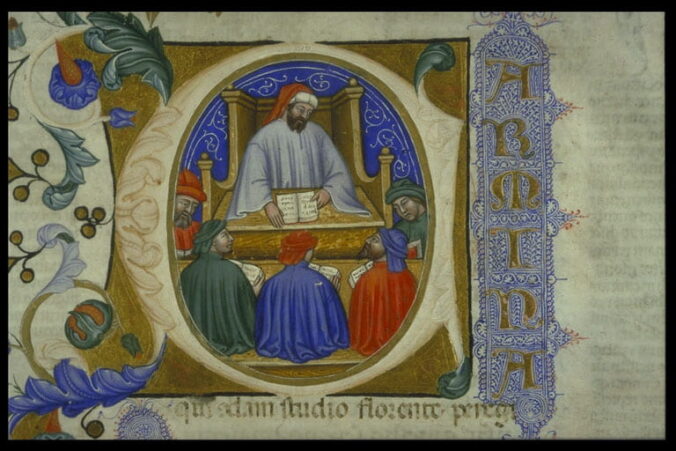

Alain de Botton – The Consolations of Philosophy

In this compact, quick read, Alain de Botton uses the ideas of six philosophers to offer consolations on everyday worries. From Socrates on unpopularity to Epicurus on poverty and Nietzsche on life’s difficulties, he brings these old philosophers to life on issues of concern in the 21st century.

Readers might bring skepticism to the table here, but I think it works well. I’m also thinking about similar work in the area of philosophical counseling. So, I found it a useful book.

However, this isn’t a scholarly work. And I could find plenty to pick at. But in the broad outlines, the book has a lot to offer people. Who couldn’t use a reminder not to get worked up about the idle opinions of others? Who couldn’t use a reminder to take a hearty attitude in the face of frustration or unrequited love?

Alain de Botton shows how the ‘wisdom of the ancients’ can work for us.

Lyta Gold – Dangerous Fictions

As a regular Current Affairs reader, I’ve encountered Gold before, and I had high hopes for this book. A great essayist takes on the role of fiction in our moral panics? Sign me up!

And Gold delivers.

She covers an impressive range of topics, turning in a well-argued work around a tough theme. More importantly, Gold questions an assumption shared by both the far right and political progressives.

What assumption is that? Namely that fiction is powerful. Gold doesn’t exactly deny the power of fiction, however. Rather, she challenges us to show cases where it exerts a causal force on the world. And she convincingly argues for the rarity of that event. In the end, only politics and class struggle do the work.

Fiction, for Gold, serves more as a proxy for those underlying forces. Her discussion of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop serves as a useful illustration. The left likes accusing the Workshop of serving as a vehicle for CIA manipulation of world politics. While Gold finds some evidence of this, she sees its actual role as an early harbinger of our cultural trend toward navel-gazing autofiction and the exaggerated importance of ‘stay in your lane’ politics. She also complicates our tendency to directly connect fictional characters to politics through, among other things, a discussion of the X-Man characters.

Finally, her nuanced and careful discussion of Gamergate stands out as another highlight. Rather than a flash in the pan, the Gamergate controversy turned out to be a cultural harbinger in many ways.

Les Leopold – Wall Street’s War on Workers

In this compact and clear book, Les Leopold – co-founder and executive director of the Labor Institute – looks at mass layoffs, the harm they do to communities, and the politics that create a financialized capitalism in which they flourish. Along the way, he serves up lessons to liberals and progressives.

As Leopold shows, mass layoffs hit working-class rural areas the hardest. And as they hit, these voters shifted from Democrats to the GOP in the 1990s and beyond. Moreover, Leopold shows extensive evidence that those voters don’t hold regressive views on social and identity issues.

Leopold reasonably concludes that these voters moved to the GOP due to economic backsliding and the lack of a secure future under neoliberal capitalism. They watched as Democrats supported the trade deals and corporate deregulation that gutted their communities. As Leopold puts it, Democrats could win them back with a progressive populist message. Millions of them vote GOP despite holding liberal social views.

While this is all well and good, I think Leopold runs into trouble when offering an explanation for mass layoffs. He opposes structural explanations to political ones, arguing that Reagan and Clinton era deregulation better explains mass layoffs than forces such as the rise of finance capital, automation, and international competition. But I see little reason to oppose those stories to one another. Underlying economic realities made the political realities more likely to occur.

Finally, Leopold lays out a political vision for the future. This includes building unions, labor centers, and third-party politics. It also includes rolling back deregulation and legislating greater worker control over businesses, thereby reducing incentives toward mass layoffs.

Samhita Mukhopadhyay – The Myth of Making It

A former editor at Teen Vogue delivers this book about the workplace and its false promises. Mukhopadhyay warns us that even in the heart of progressive culture, the workplace still offers only false, empty promises for fulfillment.

Sounds promising enough.

In the first half of the book, she offers a standard, competent history of the workplace and marginalized identities. She begins the story in the 1960s, but she covers in greatest detail the period from the Obama presidency through the Covid pandemic. Particularly timely is her focus on the limits of DEI.

The second half delves deeper into the pandemic years, focusing heavily on her personal insights. It’s here that we find the major positives and negatives of the book.

Mukhopadhyay ultimately wants to put herself on the side of workers, but she often conflates workers with mangers in white-collar orgs. But as a middle manager herself, she has real insights into their role in companies. She knows all too well that they serve as barriers to communication between leaders and workers.

On the whole, Mukhopadhyay doesn’t break any new ground. But her ultimate answer to the problem of trying to have it all – try to organize while also changing one’s mindset – is a pretty good one. And I credit her for telling an old story in a fresh way, connecting with readers with lots of personal examples.

Lyndsey Stonebridge – We Are Free to Change the World

Stonebridge wrote this book as a biography of Hannah Arendt, told through an exploration of Arendt’s philosophical ideas. But it’s really a hybrid book, neither fully biographical nor fully intellectual. She synthesizes the two forms and tries to apply the lessons to today’s world.

The story follows Arendt from a young Jewish girl in Germany to a refugee fleeing Nazi Germany to an established older American. It follows her from college student in a fiery romantic relationship with Martin Heidegger to an elder philosopher and writer who rekindles an intellectual friendship with the very same Heidegger. Over the years, Arendt continuously renews her theme of human freedom, defending it against imperialism, antisemitism, and totalitarianism.

In one of the more interesting strains of thought – and one directly relatable to today’s world – Stonebridge brings out Arendt’s complex views on Israel and Zionism. Arendt skillfully balances compassion for survivors of antisemitism with the knowledge of the problems that the creation of Israel would bring. And in another, Arendt analyzes how power recedes into the background in democratic societies. We are instead expected to perform for others in public – to approach others on the basis of our identities and private lives. We see, of course, that this is even more accurate in 2025.

More than anything, Stonebridge makes Arendt relatable. Even when she’s unable to apply Arendt’s specific ideas, the reader gets a sense of what the world was like for Arendt herself. And insofar as that succeeds, the reader can try doing the application on their own, without the need of help from the author.

Brandon Taylor – The Late Americans

This book reeled me in because it’s an Iowa City story. Taylor, once a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop (kind of a theme this month!), sets this story in and around Iowa City’s writing spaces. The characters float in and around the Iowa City arts scene. They argue in class, work in downtown Iowa City, hit the Ped Mall and familiar bars, and so on.

The book starts off promising enough, with the early lead character – the poet Seamus – coming off as a recognizably Iowa City figure. And then the story moves slowly toward increasingly less interesting subculture figures, culminating in characters like Fyodor – a local Russian meatpacking worker – who simply don’t exist in Iowa City.

Taylor writes the characters as an ensemble cast moving in and out of the story. He ends it with most of the characters – notably absent the original lead – taking a road trip out of town. This approach allows Taylor to tell a variety of distinct, but overlapping, stories.

Some work better than others. The stories of Seamus, Ivan, and Goran work reasonably well. The story of Fatima – largely ignored for the first 200 or so pages of the novel – is promising, but woefully underdeveloped.

In the end, I think the novel needed a lot more work. Perhaps it would’ve worked better as a short story collection.

Leave a Reply