Bernie Sanders lost in 2016. Cathy Glasson lost in 2018. Glasson is a Sandersista. Sanders is, well, the Sandersista.

Sandersistas have pursued many strategies since Bernie’s loss, with Cathy Glasson representing an electoral route. Sanders looms large over this strategy, endorsing candidates and providing support through organizations like Our Revolution. Doing things like organizing tenants’ unions and organizing against ICE represents an alternative strategy.

My readers won’t be surprised to find that I think there’s more potential to build popular power in the latter than in the former. Readers also already know I don’t think highly of electoralism as a central component of leftist strategy.

But elections are not totally hopeless, and they may provide lessons.

The Cathy Glasson campaign provides me with a convenient point of departure. One, I’m an Iowan. I saw the campaign literature, followed the press coverage, and know people who volunteered with the campaign.

Two, Glasson’s campaign is representative of how this strategy has gone, particularly in the Midwest. Successful candidates like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have gotten more national press, as winners tend to do. But, e.g., Cathy Glasson, Abdul El-Sayed, and Pete D’Alessandro are more typical. Sandersistas usually lose, and often lose badly.

What lessons can we learn from the Cathy Glasson campaign? That’s my topic here.

The Cathy Glasson Campaign

Cathy Glasson shares a lot with fellow Sandersistas. She’s new to electoral politics. Her background is primarily in popular organizations and organizing. She’s a nurse and Service Employees International Union (SEIU) leader. In that regard, her background is less technocratic and more popular than even other Sandersista politicos.

Glasson campaigned under the label ‘bold progressive.’ The center of her campaign was the ‘Holy Trinity’ of Sandersista politics: a $15 minimum wage, universal health care, and free (community) college.

How did Glasson do?

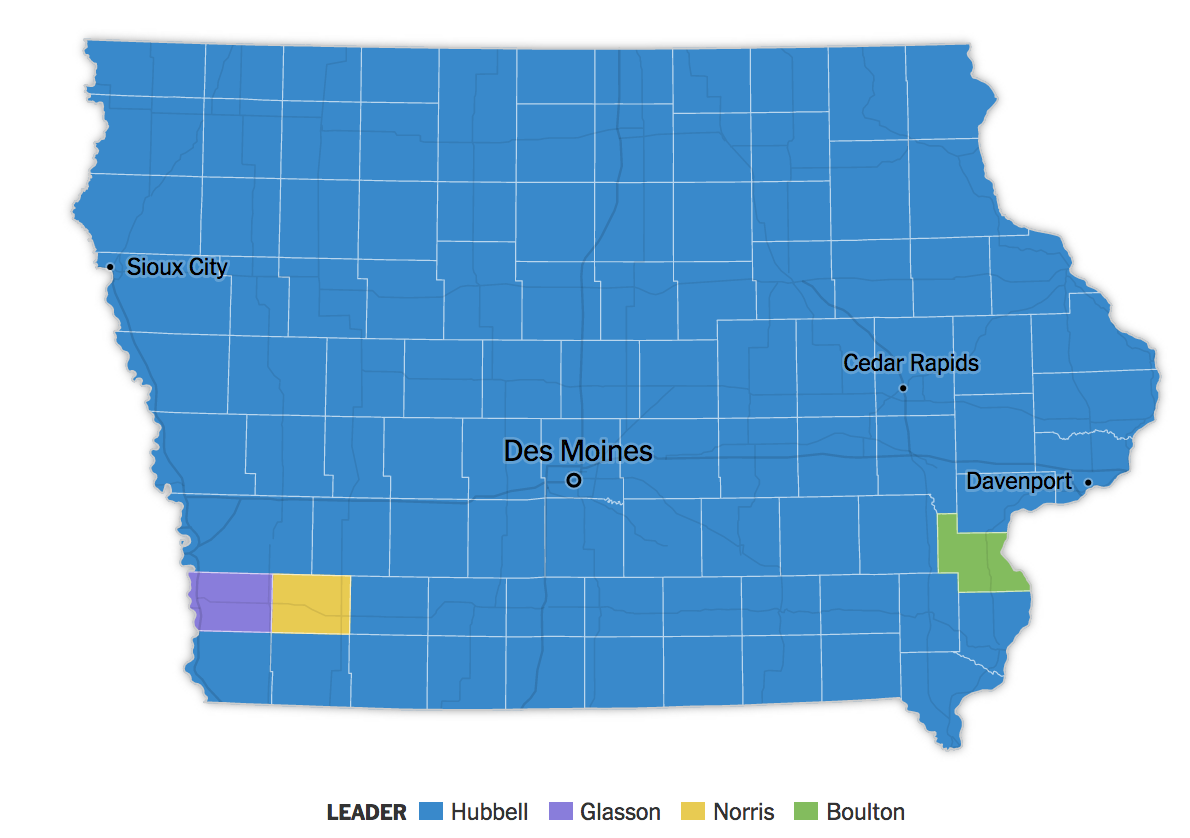

There’s no way to sugarcoat this. She did poorly. Very poorly. She won only 1 of Iowa’s 99 counties. Glasson lost urban and rural areas. She lost wealthy and poor areas, Democratic and Republican areas. Glasson was losing when she announced her candidacy. She was losing before her chief progressive rival (Nate Boulton, who I’ll say more about below) crashed and burned. And she was losing after he crashed and burned. Glasson got annihilated.

Take a look at the map.

Source: New York Times

It’s not just the sheer scale of the thrashing, but the circumstances behind it. Fred Hubbell, a generic, technocratic, centrist Democrat, won. Hubbell ran primarily on the strength of his experience as a business executive. He argued that he can become a successful chief executive of the state.

The CEO defeated the bold progressive, 55%-20%.

Why Did Glasson Lose?

Cathy Glasson supporters offer two theories on why she lost:

1. Hubbell raised and spent far more money than Glasson. He swamped the state with his campaign cash and crowded out all rivals. Had Hubbell not held a large monetary advantage, Glasson would’ve gotten her name out and won.

2. Organized labor was divided against itself during the primaries. Had organized labor united around Glasson, she would have won.

Organized Labor Unity…

We can make relatively short work of (2). In one sense, it’s a trivial claim. Yes, had everyone united around Glasson, she’d have won. OK. But this is true of every candidate. Indeed, if everyone supports you, you win. Surprise!

Examined more closely, (2) is a serious misdiagnosis. Politically, most labor unions in Iowa that endorsed candidates endorsed Nate Boulton, not Cathy Glasson. The only union that gave significant political support to Glasson was her own union, the SEIU. The SEIU not only supported Glasson, it paid for about 85% of her campaign.

This has provoked charges that Glasson’s campaign was more about the political positioning of the SEIU in Iowa than about actually electing Glasson as Governor of Iowa. I know one person interviewed for the story I linked in the previous sentence, and I trust his judgment on these issues. And so I think these charges have some merit, but I’ll set this issue aside. It goes much further into SEIU inside baseball than I’m interested in going in this post.

…and Social Movement Organizations

Glasson did have significant support from non-union organizations, but the vast majority of this support came from national progressive groups, not Iowa-based groups. Internal to the state, the Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement was the only large non-union organization to work for Glasson’s election.

The point is that if anyone had a claim to the mantle of organized labor unity, it was (pre-scandal) Boulton. Boulton became an unacceptable candidate after three women reported that he groped them. But the endorsements rolled in well before that, so this wasn’t a factor in the original decision making process.

More broadly, it’s not clear that even a totally united front of Iowa organized labor had enough power to defeat Hubbell. Organized labor has lost significant strength in both the state of Iowa and in Iowa Democratic politics.

Political Fundraising

So much for (2). How about (1)?

There’s a certain truth to (1). Hubbell did raise and spend far more money than anyone else. He outraised Glasson and Boulton by about 5-to-1. And we have good reason to believe spending money correlates with winning.

I can also lend some anecdotal support to (1). Hubbell saturated Iowa with campaign literature. Others didn’t. I received campaign spam and phone calls from Hubbell for weeks leading up to the June 5 primary. The reason, of course, is that Hubbell had the cash on hand to do this. Others didn’t. For relatively low information voters, Hubbell dominated the limited time they spend on elections.

The problem with (1), though, is that Glasson supporters overestimate the extent to which the Democratic primary electorate supports the Sandersista Trinity. Iowa Democratic primary voters aren’t an especially Sandersista-leaning group. And insofar as they are, they’re from segments of the Sandersista movement that don’t find Glasson especially appealing.

Demographics in Iowa

Your generic, most common Democratic primary voter in Iowa is white, over 50 years old, and middle to upper-middle income. Most aren’t current college students or college graduates. The vast majority already have health insurance. Most are either retired, make above $15 per hour, or are intentionally out of the workforce. You can probably get some of these people to support the Sandersista Trinity. But it’s not a quick or easy sell. It takes great skill and organization.

If Glasson had more money, she’d have probably done a bit better. A bit. Hubbell still would’ve won. Candidates like John Norris and (pre-scandal) Nate Boulton would’ve benefited far more from additional funds. Norris, in particular, was a better ideological fit to a broader range of primary voters.

There’s a similarity between this and my criticism of the claim that Trump’s base is the ‘white working class.’ For whatever reason, people have great difficulty understanding that the people who vote are systematically wealthier than the people who don’t vote. Campaigns adjust accordingly. Voters adjust accordingly. Campaigns adjust accordingly. And so on, in a feedback loop of increasingly wealthy voters and increasingly shitty politics. The people you see struggling in everyday life aren’t representative of the people who vote on Election Day.

Again, Why Did Glasson Lose?

Contrary to the views of most Glasson supporters, I think she lost for 3 main reasons:

1. Glasson was ideologically out of step with most Iowa Democratic primary voters. She advocates policies well to the left of most of the actual voters.

2. The Glasson campaign wasn’t grounded in sufficient political education and grassroots organizing of the electorate. The organizing and union infrastructure needed for the spread of Sandersista and/or leftist politics weren’t in place in Iowa.

3. Glasson did not make a compelling case to enough voters for the Sandersista Trinity as a basis for state-level policy. This is probably in large part because her campaign was mostly funded and staffed by one union. While the SEIU has an unusually large amount of gender and racial diversity, as well as good politics, one union is still too narrow for a statewide campaign. It leads to groupthink and lack of ability to speak to those not already on board. A single union, no matter how diverse, will never be diverse enough for a statewide campaign.

Who Voted for Glasson?

To her credit, Cathy Glasson wasn’t totally unaware of these issues. She knew about the problem of the establishment-loving electorate, and she knew she could never win over that electorate. Her campaign goal was to expand the electorate. In this, Glasson is the quintessential Sandersista. This is the goal of practically every such candidate, as well as Sanders himself.

It’s no easy feat to pull off. Most of these candidates don’t. Glasson didn’t. The ones who do pull it off usually have a little help from background political conditions in addition to mere ideology. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez won, in no small part, due to the fact that her opponent was a centrist white man representing a heavily Democratic Latinx district. Glasson had none of those background factors working for her.

I’m not above a little bragging, everyone. When Glasson entered the race, I predicted she had practically no chance of winning. For most of the campaign, her support sat around 5-10%. After the Boulton scandal, I predicted she’d rise to about 20% of the vote, but still go down in flames. In fact, she did go down in flames with exactly 20% of the vote.

In the messy world of political predictions, I’ll gladly accept this as a surprisingly accurate one.

Composition

But I was wrong about the composition of Glasson’s voter base. I figured Glasson would put together a reduced version of the old Sandersista coalition. I’m talking here about college students, disaffected 2008 Obama backers now in their late 20s and 30s, and wealthy white ‘progressives.’ I figured she’d do best in Black Hawk (Cedar Falls), Johnson (Iowa City), and Story (Ames) Counties. I figured she’d do OK in Des Moines and Cedar Rapids. And then lose very, very badly everywhere else.

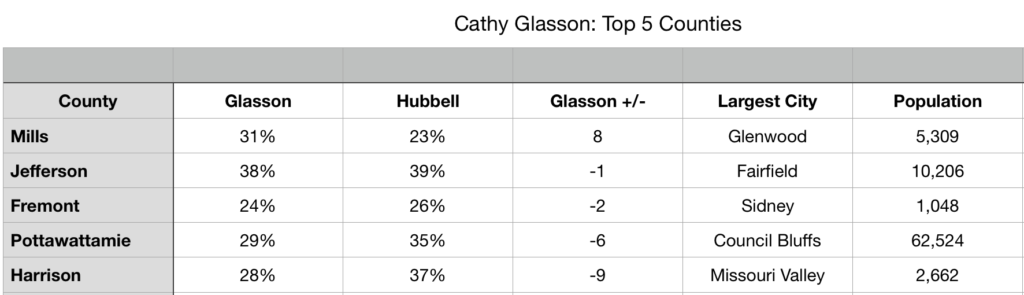

However, I was wrong about this. That’s not Glasson’s voter base after all. Black Hawk, Johnson, and Story Counties were not among her best counties. She performed horrendously in both Des Moines and Cedar Rapids. All of her best counties were in rural areas of the state, particularly areas where low wage work dominates.

Here’s a table showing Glasson’s best counties.

This is mostly a table of rural counties that aren’t full of college students or wealthy white progressives. Only one county contains a city among Iowa’s top 10, and that city is #9 (Council Bluffs). What they are full of, though, is low wage workers, disaffected voters, and working class liberals and leftists who feel that no one represents them.

So, who voted for Glasson? Very few wealthy white progressives. Probably a few college students, though far fewer than voted for Sanders in 2016.

Glasson’s base was probably low wage workers, particularly those who live in rural areas and small towns. If nothing else, that’s interesting. It’s a group of people who haven’t engaged heavily in electoral politics in a long time.

Lessons

I think there are a few lessons we can learn from the Cathy Glasson campaign:

1. Electoral politics are not a good short-term strategic focus for the left. The pool of potential leftist voters is both too narrow and too shallow for short-term electoralism to bring results.

2. We need background work on organizing and political education. For two reasons. One, to build more supporters, and, two, to provide current leftists with a deeper understanding of the hows and whys of building movements.

3. In its current form, the best thing electoral campaigns do is bring a wide range of people together to share ideas. A consistent theme I’ve found in speaking with Glasson volunteers and staffers is that they met people doing interesting organizing work outside of electoral politics. People working on the Fight for $15. Working to fight ICE and fight alongside immigrant families. And so on. But we don’t need an electoral campaign to meet people doing good work. We need to make our wage, immigration justice, et al. campaigns more engaging, so that people spend more time on those than they do on electoral work.

4. Broad coalitions win statewide. One union isn’t enough, nor is one union plus some SMOs. The dilemma for some candidates is that they think broader coalition-building may require them to dilute their policies. At the moment, that’s maybe true. The solution is to engage in political education and organizing aimed at creating both broader and deeper support for leftist political ideas. When there are more of us, we don’t have to dilute our campaigns.

5. There’s a lot of potential to organize with low wage workers, both in electoral campaigns and in campaigns around wages, wage theft, racial justice, immigrant justice, and other issues. The interest is there.

You don’t see it. Glasson motivated the very people who refused to vote in the last Presidential election. Many of the very Demexit, disenfranchised, and Independent votes we most need and yet fail to motivate. It was unwise to choose a lieutenant gov candidate on the ticket that removes a held Dem seat in the legislature and at the likely expense of losing the particularly fragile votes Glasson brought to the primary polls. I fear another Reynolds term if Hubbell does not make a very, very sincere effort to reach out to those voters. I also see his campaign failing to reach out to the potential Black voters in Johnson County if he doesn’t show up at Soulfest this weekend after an effort to reach out to his campaign on the importance of it several weeks ago.

What the Dem candidates, IDP, and DNC continue to fail to realize is that they need to stop working so hard to please blue dog Dem votes they already have in the bag and, instead, work their asses off to personally, in person, court the potential disenfranchised Dem, Demexit, & left-leaning Independent votes that have repeatedly shown they will not show up to the polls for anything less.

I think we clearly agree on one thing: motivating left-leaning and independent non-voters was a big part of Glasson’s goal in the campaign. She did some of that, which is why she did well in some of the rural and/or forgotten counties. But she didn’t do nearly enough of it to win the primary, and I tried to give a few reasons why above.