Sociologists Michael McCarthy and Mathieu Hikaru Desan recently sketched out their response to the class reductionism debate. Their approach lines up rather nicely with the one I took in a post and article. But they also make conceptual space for views I think we can see floating around in various forms. I want to take a look at one such view: class constructivism.

I’ll start by saying a word about how McCarthy and Desan lay out the conceptual space. And then I’ll move on to sketch out class constructivism. While few views completely fit into the class constructivism camp, I think we can find appeals to something like it within common perspectives in both DSA and the broader left.

McCarthy and Desan on Class Reductionism

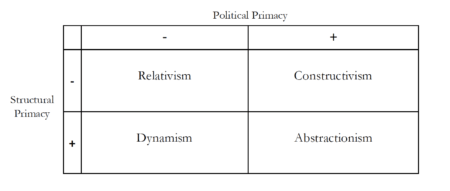

As McCarthy and Desan put it, class reductionism amounts to the claim that class holds primacy over various identity categories. They distinguish between two types of primacy of class: structural and political. The structural primacy of class amounts to the claim that it plays a fundamental role in determining the basic structure of society. The political primacy of class claims only that class ought to play a more fundamental role in political mobilization and activism.

Structural and political primacy correlate loosely to what I called in my own article ‘explanatory priority’ and ‘political practice and movements,’ respectively. My work also addresses historical priority and lived experience, which McCarthy and Desan do not address directly. But they’d probably see the former as relevant to structural primacy and the latter as relevant to political primacy.

So why do they distinguish between structural and political primacy? They sketch out four possible views of class reductionism that come from plotting the two kinds of primacy together on a map. Here’s what that looks like:

In the rest of the paper, the authors argue, not implausibly, that criticisms of class reductionism mostly target Class Abstractionism (i.e., the claim that class has primary over identity categories in both the structural and political sense. They argue instead in favor of Class Dynamism. This is the view that while class has structural primacy over identity categories, it might not have political primacy.

I won’t address all those issues here, but I think they’re on the right track. My own view is probably a form of Class Dynamism. But, in line with the title of this post, I want to address the top right quadrant of the graphic.

Let’s talk about Class Constructivism.

Class Constructivism

So, the graphic above says a bit about Class Constructivism. It amounts to the view that class holds political primacy over issues of identity or culture. We should build our political movements or tendencies on the basis of class or economic language and formations. But the class constructivist holds an ambivalent or even negative attitude toward the idea that class has structural primacy.

Some readers might find that surprising at first glance. After all, ‘traditional’ Marxists derived the political primacy of class from its structural primacy. That is to say, they claimed that because class acts as the fundamental force, we should focus on it in our politics. Workers of the world unite, and all that.

Class Constructivism takes a different path. Its defenders take seriously the turn away from grand narratives in sociology, social theory, and also in the actual practice of politics and organized labor. And away from Marxist grand narratives specifically. And so, they drop the idea that class functions in the fundamental explanatory role structural primary would hold.

However, they still want to prioritize class in their politics. They think the language of class – specifically its grasp on universalism – can unite people together into a political program. It can do so even in an otherwise ‘postmodern’ world that no longer features universal political formations.

Who Holds Class Constructivism?

So, who holds such a view? McCarthy and Desan cite the theorists Laclau and Mouffe, specifically. And they cite ‘left populism’ more broadly. They think the view traces to a post-Marxist turn in left theory in the later 20th century.

Perhaps that’s right. I’m not an expert on Laclau and Mouffe. But I do think McCarthy and Dean correctly include in the category of Class Constructivism various kinds of ‘left populism’ that talk about class without anchoring it in the kind of social theory that places class in a fundamental explanatory role. Occupy Wall Street – with its “we are the 99%” language – fits well into this camp. It provides a way of talking about ‘class’ in a way that includes almost everyone and replaces Marxist notions of class with vague appeals to income and wealth inequality.

I think we also see Class Constructivism in the social democratic political framework of A. Philip Randolph. While his views about structural primacy seemed complicated and unsettled, he clearly prioritized a class approach to politics.

Finally, I think we can see Class Constructivism in organized labor and labor based political activism in the U.S.

Organized Labor and DSA

And it’s within organized labor that I think Class Constructivism finds some of its most interesting – and most problematic for the left – expressions. I pointed out in an earlier post that DSA organizes around core issues rather than people or classes. It builds into this a kind of political primacy of class, where the org focuses on economic issues, broadly construed. In that sense, it aligns quite well to Randolph and also to what we see in the nuts and bolts operations of organized labor.

Organized Labor

In its earliest days, organized labor had a powerful core of revolutionary unionism. We saw that with various Marxist and anarchist labor traditions, e.g., the IWW. But today most unions express the (often narrowly tailored, and usually short term) interests of their members. They rarely work toward a deeper vision for working class success, and they rarely even commit to a viewpoint about the structural primacy of class. They obviously center class in their own labor politics, but they don’t typically reach beyond those politics.

In fact, this is true both of the mainstream labor movement and various ‘dissident’ and more leftist labor formations, such as Teamsters for a Democratic Union.

I should clarify the claim I’m making here. I’m not claiming that unions – mainstream and dissident traditions alike – fail to speak to concerns other than the salary and benefits of their members. In fact, many do. They negotiate for quality and comfort of work, more time off, and so on. Nor am I claiming that they don’t involve the community in their struggles. Segments like Labor Notes and Jane McAlevey explicitly advocate for this. And many unions do it.

Rather, my point is that mainstream labor – and most ‘left’ and ‘dissident’ labor traditions other than the IWW – still decline to commit to any actual view about the deeper structure of society and the need for revolutionary change. Let alone a vision for a deeper, united working class and how to get there. Instead, they use class focused formations and language to bring unions and community members together to achieve specific wins in specific workplaces.

DSA Labor

The lack of commitment to the structural primacy of class and the need for revolutionary change make things difficult for a group like DSA in its efforts to work within organized labor. DSA Labor bears the brunt of these difficulties.

Why? There’s a tension at work. DSA focuses on strike support and networking with dissident labor leaders. These efforts have been productive. Strike support can help DSA members think of themselves as also members of a ‘multiracial working class’ (in DSA jargon). Networking can help put DSA on the map of labor orgs. It helps them see us as good partners.

But even when these efforts succeed, they rarely make existing unions more revolutionary or more socialist. It rarely helps DSA recruit union members to our org. To do those things, DSA should focus more on direct organizing of new unions that do include the structural primacy of class and a vision for a deeper working class politics.

DSA and Class Constructivism

This all takes us back to the language of ‘Class Constructivism’ that McCarthy and Desan lay out for us. Much of organized labor, and by extension many DSA Labor campaigns, build around class constructivists visions. But those visions run into limits.

As I’ve argued in my own work on class reductionism, these visions lead us to overlook situations where gender, race, and other identities rise to the surface of our politics. And so, we must supplement our organizing with a politics focused specifically on issues of identity. By, say, holding directed outreach for members of marginalized groups.

But second, and more important in this post, we have to acknowledge that organized labor – even left-leaning dissident labor traditions – still mostly fail to see the structural primacy of class. This limits labor’s power to ever live up to its revolutionary potential.

A good DSA Labor campaign makes space for solving that problem.