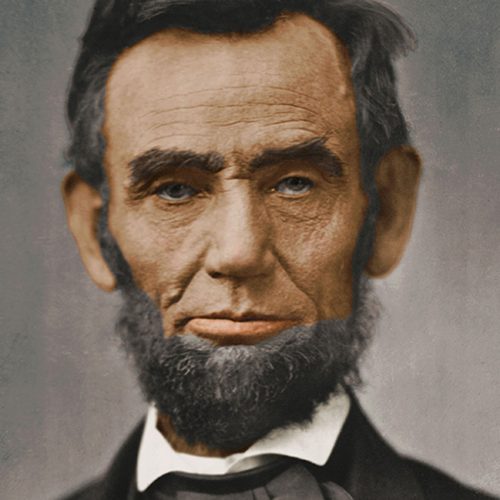

In On Writing Well – his classic guide to writing nonfiction – William Zinsser quoted Abraham Lincoln on politics and morality. In his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln said:

It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their break from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we not be judged.

Zinsser approved of the quote. I suppose I can’t argue with Zinsser. He didn’t just write the book on writing, he also wrote the book on spring training.

But quotes like this make people nervous. Especially activists who center their politics on issues of identity. Many think that to separate politics from morality is to excuse the worst behavior. Their political dial holds no setting between moral politics and libertarian permissiveness, moral relativism, or apologism.

Class Politics and Morality

I don’t like that dichotomy. I think the left would be better off replacing morality as a motivator. And I think it should do so without lapsing into the other side.

Why? A couple of reasons. First, I think morality drives people far less than many leftists think it does. Just about every introductory leftist text begins with a moral appeal. Maybe it does it by appealing to ‘human rights.’ Or maybe it does it by appealing to outrage over the behavior of bosses or landlords, et al. But all these things fall under the general heading of ‘moral appeals.’

This appeals to specific political sectors, notably people who already identify as politically progressive. Far from a way to attract new people to the left, I think moral appeals tend to reach the already converted. Focusing on morality is helpful for driving leftists to action, but it doesn’t win many converts.

Second, morality doesn’t drive me, personally. I get the pragmatic value of using moral appeal to stoke outrage and action. But class politics drive me, not moral politics. I think working people and tenants can and should unite to promote their collective interests. If there’s a morality here, it’s one that’s internal to – or the servant of – class politics.

The Challenge

And so, the left faces a challenge. Can we appeal to class politics so effectively that we no longer need the moral appeals? Do we really need to start every book and speech with a list of capitalist or landlord outrages?

Can we – and this is perhaps the greatest challenge – explain to new leftists why we should overthrow capitalism even if workers and tenants are treated relatively well by their bosses and landlords? Because, as socialists know (or should know), even the well paid worker suffers from alienation and exploitation. Even the tenant paying a low rent pays the landlord for a good that should be free.

Slavery is a moral outrage. And I obviously limited my options in using it as a lead example. Any objection to slavery likely involved moral appeal. But class politics do provide us with tools. Notably they provide us with the tool of ‘primitive accumulation.’

And so, even in extreme cases class politics have options beyond moral appeal. If the left can use those options, it’s golden. We can expand our audience and build a bigger base.

William Zinsser, Again

Zinsser didn’t praise Lincoln’s quote for its content. He loved its style. Lincoln assumed with his audience a shared familiarity with the King James Bible. The quote above drips with references to it. The same couple of sentences include ones to the Book of Genesis and the Gospel of Matthew.

Zinsser included a second Lincoln quote on the same page. Most leftists approve of this one. Lincoln said the Civil War should continue:

…until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’

And so, Lincoln didn’t take ‘moral relativism’ too far.