College students turned out in droves to vote for Bernie Sanders. Among voters under the age of 30, Sanders won about as many primary votes as Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, and Ted Cruz combined.

‘Under 30’ and ‘college student’ aren’t the same group. Some college students are over 30, and many people under 30 aren’t college students. But there’s a lot of overlap. We also know that voters, as a group, have a higher socioeconomic status than non-voters. It stands to reason, then, that college students make up a healthy portion of the under 30 vote.

My own Iowa caucus site sits on a college campus. While the site covers both student and non-student neighborhoods, it overflowed with Sanders supporters. He won 77% to Clinton’s 23%. Nothing was more obvious than the age difference between the two camps. And, despite attempts to label Sanders a candidate for only white people, he carried the under 30 vote nationally across all racial groups.

Local elections are a different story. Turnout is low among basically all ages everywhere across the country. But it’s really low among young voters.

Given the facts about who votes, you’d expect turnout to be very low among young people who don’t go to college and relatively higher among those who do. And turnout is low among those who don’t go to college, in both national and local elections. College students, though, don’t behave quite as expected. They do often vote in national elections but don’t vote in local elections.

Why is that?

Iowa City Council Elections

I’ll approach this issue by looking at the recent city council primary in Iowa City, where I live. I’ll draw lessons from Iowa City that I believe apply elsewhere, particularly in midwestern college towns like Ames, Lincoln, Bloomington, Madison, and Urbana-Champaign.

Turnout in city council elections in Iowa City is usually low. In the last decade, it ranged from 10% to 22%. The recent primary was no exception, clocking in at about 9%. That’s a bit on the low end, but this was a primary for a special election. If anything, it wasn’t quite as low as it could’ve been.

But there’s low turnout and there’s low turnout. College students dominate 4 of Iowa City’s 24 precincts. For anyone local to Iowa City who’s following along, those are IC-03, IC-05, IC-11, and IC-19. Several other precincts have large student populations, but no others have student supermajorities.

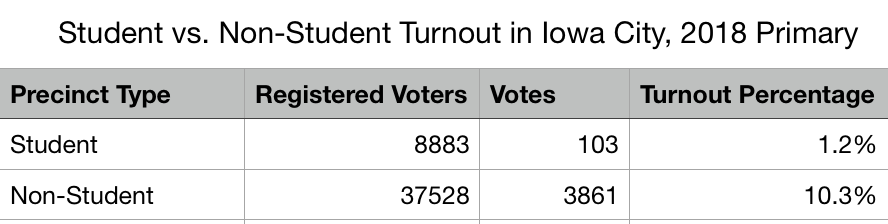

What happens when we compare those 4 precincts to other 20? This is what happens, Larry.

Note: All data can be found with the Johnson County, Iowa Auditor’s Office.

As I said, turnout was low everywhere. But non-student precinct turnout was about ten times higher than student precinct turnout. Literally only 103 people showed up to vote in the four student-dominated precincts. Poll workers were playing the Maytag repairman.

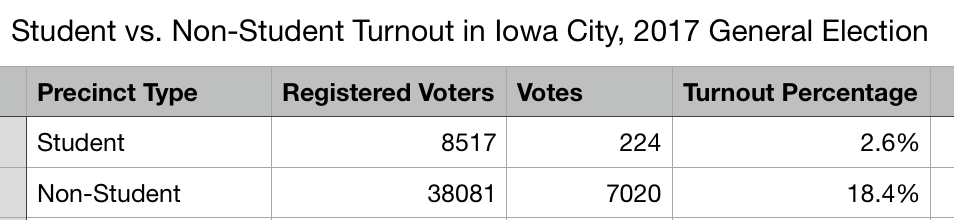

And to show this is no special election fluke, here’s the same data from the last November general election.

This is roughly the same proportion: close to a ten-to-one turnout advantage of non-student precincts over student precincts.

One quick note is that these data do not include early voters, who made up about 10% of the electorate. But I’m not too worried about that. Early voting is generally not more common in student precincts than in non-student ones. And there’s even a decent chance these data understate the difference between students and non-students. Some students live in non-student precincts and probably drag down the turnout numbers in those.

College Students and Local Elections

I’ll get to the point. I think the primary explanation for college student non-voting is that students don’t believe they have any material interests at stake in local elections. They don’t think they have any skin in the game. In this, students have a lot in common with non-student young people and working class people.

The power of this explanation is that it also accounts for why college students do often vote in national election. Non-student young people and working class people have low participation rates in both national and local elections. But for students, there’s a yawning chasm between national and local elections. The reason is that students have material interests at play in national elections, and these interests are obvious to them. Non-student young people and working class people, by contrast, are heavily marginalized by both national and local politics. No one is fighting for them anywhere.

I think this explanation is also true to student experiences. Many, probably most, students moved to their college town from somewhere else. Many, probably most, students plan to leave town within 5 years of arrival. Take a student from Mason City, Iowa who’s a 21 year old junior in college at the University of Iowa. Suppose, further, that they’re hoping to take a job in Chicago or Minneapolis after graduation. This student most likely believes they’ve got no real stake in, say, voting a 4-year term to a city council candidate or even a 2-year term to a state legislator.

Alternative Explanations

Organizations looking at the issue of student voting tend to propose much more comprehensive explanations. The Knight Foundation, for example, cites a variety of issues. This includes media coverage, lack of understanding of government, skepticism about government, local civic pride, and identification of polling location. The full report is worth reading, but I find it a bit scattered.

The trouble with these more comprehensive explanations is that they tend to assume that students are wrong to believe they don’t have material interests at stake in local elections. Better media coverage, better education, civic pride, and polling information will work only if students actually have material interests involved that they just don’t know about. They need to be, so the Knight Foundation line goes, told about their interests.

I’m much less confident in any of that. Sure, better advertising will probably bring a few more students to the polls, particularly given the catastrophically low 1% turnout rate. But how many? 3%? 5%?

I suspect, on the contrary, that students are correct in taking themselves not to have a stake in local politics. And that, ultimately, this is the reason college student turnout is unlikely to rise to a point anywhere near non-student turnout in the near future. At least, not without serious structural changes in local politics.

Solutions

Students aren’t averse to local issues and local organization. I’ve been personally involved in umpteen student organizations, and other organizations that had many students as members. College students are no worse than anyone else at figuring out what they have a stake in. They’re no worse than anyone else at organizing around common interests. If anything, students might be even better at some of this.

For the most part, then, the organizing work that students are doing is more important than voting. And so, to some degree, the kids are alright. There might be less of a problem here than meets the eye.

But, if people really do want students to vote in local elections, they need to create political systems and political realities that encourage student voting. They need to give students a stake.

To be clear, I’m not talking about things like having a special seat for students on city councils. Or having student representatives sit in on legislative meetings. That’s the kind of hokum that sounds good, but it’s not really grounded in anyone’s material interests.

Nor am I talking about students running for office, though I certainly have no objection to students doing this. There was a student candidate for city council in both of the elections in the tables above. This had zero positive impact on student turnout in those elections. Merely having a student on the ballot is insufficient to show that students have a stake in the outcome.

What would need to happen is something a bit more creative. What are local mayors, city councils, and/or state legislators doing to advance student interests? And not just hypothetical future interests, but student interests now. Are they working on public housing proposals? Are they fighting for universal healthcare, free college, loan forgiveness for existing student loans, better mental health services, support for victims of sexual assault, anti-racist policies, restrictions on use of police to issue fines to students, and other issues relevant to students?

If not, why the fuck would students vote for them, anyway?

Special Bonus: When Students Vote in Local Elections

I’ve argued in this post that students don’t vote in local elections because they don’t believe they have a stake. I’ve also argued that, in fact, most probably really don’t have a stake.

But what if they did have a stake? Would they recognize it? Would they vote?

It turns out we have a pretty good case in Iowa City. In 2007, there was a measure on the ballot called Public Measure C. This ballot measure would’ve banned everyone under the age of 21 from being on the premises of bars after 10pm.

Students had an obvious stake in this. And they voted en masse. In that election, 3717 people in the four student precincts I identified above either requested an absentee ballot or voted on election day. That’s 3717, compared to 103 (this year’s city council primary) or 224 (last year’s city council election).

It’s obvious enough that college students aren’t always allergic to voting. They’re allergic to voting when it’s not worth their time.