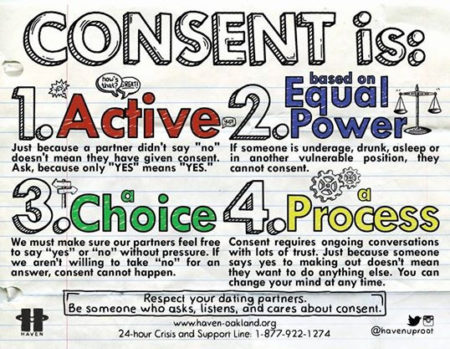

By now I’m sure many of us know that the choices we make are far more complex than popular debate suggests. Almost everyone agrees on the need for consent, on at least some notion of ‘consent.’ But whether and how we consent – and what kind of consent we need – remains less clear.

I might approach these issues in a million ways. But here’s one way. I recently re-read a blog post on Feministing. The post covered a 2014 study in Psychology of Women Quarterly on gender and choices about body hair. It turns out that a woman’s decision to remove (or not remove) body hair is a pretty complicated one. In particular, the social pressures involved cloud the matter of whether and how women consent and make choices.

Body Hair and Choice

So, both the blog post and study point out that women have choices about body hair removal. In most cases, they can shave their armpits or legs. Or they can not do those things. For that matter, men (and non-binary people) have the same choices. Simple enough, right?

Not quite. In fact, the study shows that many woman spend a lot of time navigating the complexities involved in these choices. Why? The study reveals that many people (often most people) hold default expectations about what women choose on these matters.

This means that anyone who goes against the grain (no pun intended) on these matters takes on a certain amount of risk and struggle. Often quite a bit of struggle. And so, there’s a strong imbalance in choices. For women, it’s simply much easier to conform to social expectations on body hair. It’s much easier to shave and avoid having to constantly explain yourself to others.

Beyond this core base of the study, the Feministing points out relevant intersections, particularly among trans and/or black women. Since trans women face additional pressure to ‘pass’ as their identified gender, they face extra headwinds against nonconformity. And some black women report extra social pressure to conform to norms about body presentation that they identify with white people.

Gendered Choices

So, it seems to me we can extend many of these points to a wide variety of gendered choices. How many women report the ‘choice’ to change their last name at marriage? And how many do so in order to avoid having to endlessly explain a difference choice to family members who disagree or won’t understand? How many people ‘choose‘ monogamy because it’s the default and it’s much easier to find partners who assume it? And so on.

These questions don’t have easy answers. I’m not looking to claim that social expectations invalidate people’s choices. Choosing to change one’s name at marriage, et al., can be fine. But we do need to acknowledge that the world puts its thumb on the scales in ways that can distort and muddy issues of choice and consent.

Default Expectations

Finally, in thinking about this topic, I returned to thoughts from my philosophy days and first book. In that work, I stressed the importance of default expectations to how we navigate and think about the world. As I presented it, a ‘social practice’ involves some default way of inhabiting the world.

But this is hardly static. In fact, our ways of inhabiting the world change over time. Sometimes it changes too slowly to notice right away. But it affects us, and it changes both how the world treats us and what we expect from it. In a recent post, I even took up an example of this phenomenon – the feminization of work.