Welcome to the final reading list post of 2022! Don’t worry, there will be more in January 2023. But there won’t be any more this year. So what have I been reading at the end of 2022? Read on to find out. And, as always, let me know what you’ve been reading.

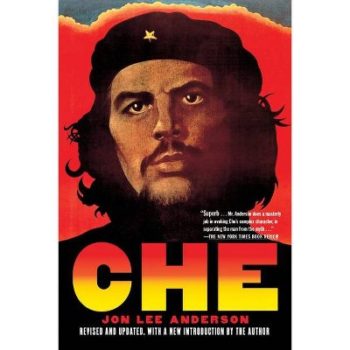

Jon Lee Anderson – Che

Readers might recall Che Guevara’s diaries about a motorcycle trip across South America from the September 2022 Reading List. This full life biography of Che expands on that material quite a bit.

Anderson positions himself as neither enemy nor full ally to Che. This allows him to evaluate Che’s life without the bias of either the anti-communist or the Che acolyte. That’s rare enough.

And he puts those skills to good use. He traces the broad arc of Che from carefree youth to hardened anti-imperialist and guerrilla fighter. Anderson puts it best in the book’s final pages: “Che’s unshakable faith in his beliefs was made even more powerful by his unusual combination of romantic passion and coldly analytical thought. This paradoxical blend was probably the secret to the near-mystical stature he acquired, but seems also to have been the source of his inherent weaknesses – hubris and naïveté.”

These traits drove Che and led him to both victory and defeat. They still lead people to adore him. Even decades later when I began my own activism, one could find plenty of Che admirers in activist groups.

Emily Guendelsberger – On the Clock

Guendelsberger goes out and gets three low-wage jobs. She looks at life through the lens of workers left out of the shiny, white-collar job market the U.S. advertises as its main economic force. Readers might think this sounds a lot like what Barbara Ehrenreich did in Nickel and Dimed. And they’d be right. Guendelsberger takes up a similar project.

But she puts a novel spin on it. For one, she chooses jobs from today’s tech and process improvement economy. Those jobs include picker at an Amazon Fulfillment Center, call center work, and McDonald’s worker.

Each workplace presents its own spin on scientific management. Amazon pays better than the other two, but it tracks her movements with authoritarian zeal and pushes her to her physical and existential limits. The call center and McDonald’s demand endless emotional labor. McDonald’s pits workers and working-class customers against one another in endless battles.

Guendelsberger also does a nice job integrating the science of physical and emotional abuse into her personal account. This allows her to paint a more complete picture of having one’s every movement and minute controlled by a money-making machine.

Robert Heinlein – The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

This isn’t the first time I’ve read this book, one of the best known novels from one of the best known sci-fi authors. Readers thinking about picking it up should do so for that reason alone – that it’s one of the best known novels from one of the best known sci-fi authors.

But for anyone looking for more reasons, I’ll say that it’s a classic study of revolutions and how they function. Heinlein was a libertarian, so perhaps that’s not your cup of idea. It’s certainly not mine. But it’s a great story, well told. Pick it up.

Bandy Lee (ed.) – The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump

In this edited volume, Lee puts together the voices of a couple dozen psychologists and psychiatrists to examine Donald Trump’s behavior and warn the country about the state of his mental health and its impact on the U.S.

Readers familiar with these professions will notice an obvious problem. They tell its practitioners not to do this. Psychiatry enshrines the principle in the form of the Goldwater Rule. This rule instructs psychiatrists not to diagnose public officials they haven’t examined as a patient.

As a result, much of this book reads like a series of (mostly bad) arguments for why its authors aren’t violating the Goldwater Rule. At other times, it reads like a series of attempts to carve out Trump as an exception to the Goldwater Rule. Given that they named the rule after a U.S. presidential candidate, it’s hard to see how that move works.

Though these things loom over the book, the essays do have some value. Authors point out real concerns with Trump. One does a nice job reviewing her work with patients who felt anxious after Trump’s 2016 win.

But the core project just doesn’t work. Having mental health pros point out concerns is perfectly fine. But having them diagnose Trump with mental disorder – while also qualifying that they’re not really diagnosing him – is no good. Many authors – myself included – have shown how using diagnostic labels as a weapon can do real damage in the world. This book was a bad idea, and it shouldn’t have been published.

Michael J. Sandel – The Tyranny of Merit

Sandel – a political philosopher – delivers here an argument against the ideal of meritocracy. He argues not only that society fails to live up to meritocratic ideals, but also that meritocracy itself is a bad idea.

How so? First, Sandel points to the damage it causes. Politically, for example, it led to the backlash of Brexit in the U.K. and Trump in the U.S.

Second, he argues that a meritocratic society would not be a just society. It wouldn’t even be a good place to live. Meritocracy, according to Sandel, harms both privileged people and the downtrodden. In privileged people, it produces emotional stress and anxiety. And, of course, it does material harm to others.

As far as it goes, Sandel writes clearly and writes well. But as a leftist, I have to raise the usual problems with these liberal accounts. Sandel uses basic principles of justice to write about social ideals and the just society. But all this mostly ignores facts about the way society and social systems actually work. It ignores who can change it and how change happens.

For a routine example of this, one can have a good classroom discussion about the moral question of whether luck-based talents justify inequality. Sandel even gives plausible, well argued answers to these questions. But none of this engages with the fact that a capitalist system will put these talents – whatever their origin – to use in gathering profits. That’s what capitalism does, and to change it is to reject capitalism.

And so, like much of what happens in analytic political philosophy, Sandel often writes parallel to the actual world.