Hello, and welcome to the second edition of the 2023 reading list series! It’s still winter in Iowa. And I’ve been reading a wide variety of things as of late. Only 4 books in this edition. But they cover everything from Roman history to the history of philosophy to American history to physics and race.

Enjoy, and let me know in the comments what you’ve been reading lately!

Peter Adamson – Philosophy in the Hellenistic & Roman Worlds

This is the second book based on Adamson’s podcast A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps! It picks up at about the point the first one left off: at the end of the career of Aristotle and his students.

Adamson goes on a tour of philosophy in the Mediterranean world from the conquests of Alexander to the end of the Western Roman Empire. This includes the Greek Hellenistic world, the Latin Roman schools, Neoplatonists, and Christians of the late Empire.

As readers might imagine, I preferred the units on the major pagan philosophies of the Epicureans, Stoics, and Skeptics. I’m not too interested in Neoplatonism, and hardly at all in Christianity. But Adamson does a solid job discussing all of them. He tells the story simple and well.

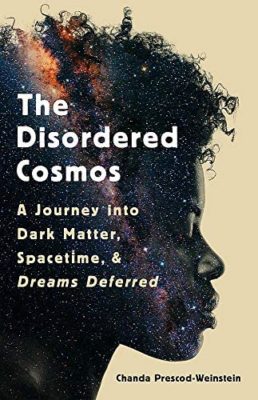

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein – The Disordered Cosmos

Prescod-Weinstein makes her mark here as the first black women in the genre of popular science writing in theoretical physics. And she seamlessly combines her own story with all the things readers expect popular science writers to do. In doing so, she approaches through the lenses of black feminism and the study of Science, Technology, and Society (STS). Given my own STS history, I can appreciate the approach.

I think she balances all these things well, especially for a first popular science book. The science can be chewy and difficult to follow, which happens in all science writing but especially authors new to the genre. But the way she weaves the science with feminism, STS, and her own story helps in this regard.

The book really shines in the portion where she discusses physics and race together. The chapter ‘Black People are Luminous Matter’ is a real highlight. And Part 2, where she makes this crossover a special focus, is easily the strongest of the book’s four parts.

Finally, as a leftist interested in the intersection of the left and identity politics, I learned some things from Prescod-Weinstein’s story about MIT cleaning staff members from Jamaica and Barbados. The staff took a special interest in her. Even going so far as to make her a special dish when her grandmother died. Leftist politics often lack these gestures of solidarity. Often because we fail to build genuine, broad alliances.

Gore Vidal – Lincoln

After enjoying the first book in Vidal’s Narratives of Empire series, I picked up the second book. With this one, we have a comprehensive (and interesting mix between fictional and factual) look at the life and times of Abraham Lincoln!

While the story focuses on Lincoln, Vidal tells it through the people and events around him. We see the mid-19th century world and civil war through Lincoln’s personal secretary, his cabinet members, and one of his enemies spying for the Confederacy. On the whole, they paint a picture of a complicated man and brilliant politician. But one who’s not all that great a war strategist.

I find a number of interesting connections between this and Burr, the first book in the series. But one theme that stands out – Vidal likes to contrast the image of the greatness of historical figures with the more complex reality. Many politicians even get credit for things that most people in their own time thought they handled poorly.

Chris Wickham – The Inheritance of Rome

I read this book as a natural follow up to the books I read recently on the history of Rome and the fall of the Roman Empire. It’s the second book in the Penguin History of Europe series. And, if nothing else, I can say that Wickham delivers an ambitious book.

Wickham tells the story of Europe from 400 to 1000. That is to say, it’s a sweeping history from the final century of the Western Roman Empire through the Dark Ages and up to the beginning of the High Middle Ages.

The real strength of the book is Wickham’s balancing of the general and specific. He focuses mainly on economic history, telling us a lot about trade around the Mediterranean, the localization of economies in Europe in the 7th and 8th centuries, and the challenges of all the states of the day – from the hybrid Roman and Germanic kingdoms of the West to Byzantium in the East. He even covers the Arab conquests and the early Arab states, since they engaged with Europe.

I think the book balances lots of newer trends in the history lit. Many authors, for example, posit climate change and disease as major movers of history. By contrast, Wickham focuses on economic history and underlying causes. I suspect we find the truth in the middle (but closer to Wickham).