The Democratic Party has had a tough time keeping the left in line. Lately it’s engaging in endless hand-wringing over alleged “Bernie-or-bust” Democrats, even though more Clinton primary voters supported John McCain in 2008 than Sanders primary voters supported Trump in 2016. More recently, Democrats frame their arguments to the left in terms of harm reduction.

Is ‘harm reduction’ a new argument? Or is it just a warmed over version of the ‘lesser evil’ argument? Is it a good argument? As a result of these considerations, should we vote based on harm reduction?

I’ll address these questions below.

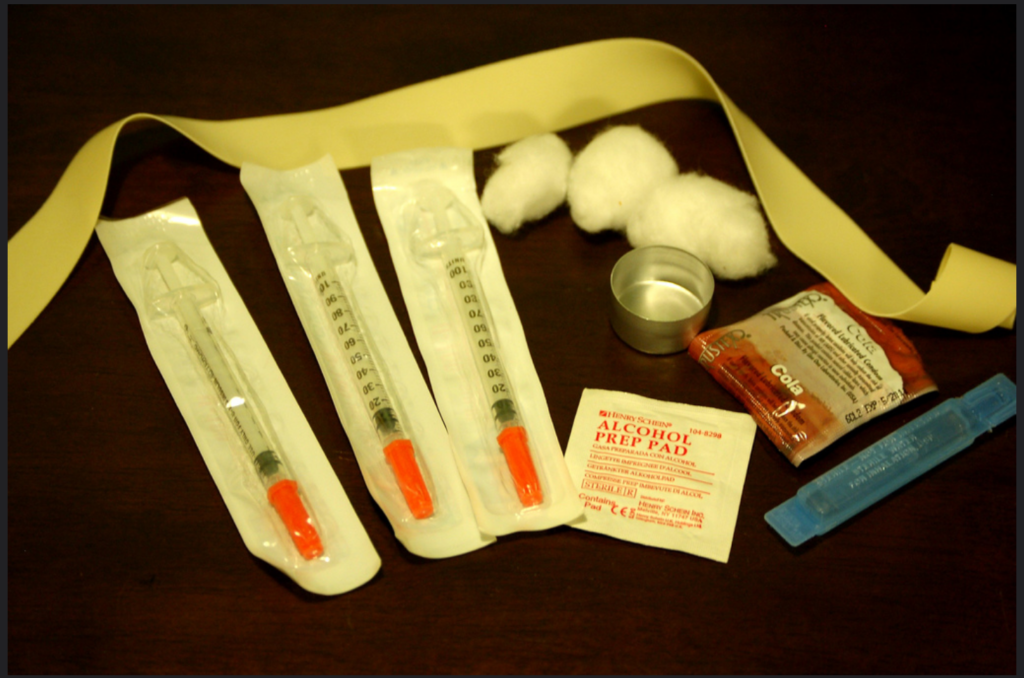

Source: Todd Huffman (https://www.flickr.com/photos/oddwick/2344377068)

What is Harm Reduction?

The term ‘harm reduction’ comes from the public health community. We can use a harm reduction framework to talk about things like sexually transmitted infections or sex work. But the primary usage of the term references substance use and abuse.

The basic idea behind harm reduction is that people are committed to engaging in certain risky behaviors, and so we’re unlikely to stop them in the short- or mid-term future. Therefore, the best way to address resulting public health crises is by minimizing the negative consequences of those behaviors.

What does this have to do with politics? Why did people start using ‘harm reduction’ to argue in favor of voting Democratic?

That’s not exactly clear. I suspect the language comes from Silicon Valley and NGO circles, as some have argued. Silicon Valley is notorious for taking terms they like and using them completely out of context. See, for example, Silicon Valley and ‘artificial intelligence.’ But I don’t think, as does the author of the article I link above, that it simply reduces to the ‘lesser evil’ argument.

I think there’s a novel thesis in there somewhere, and I’m going to extract it.

Two Kinds of Harm Reduction Arguments

Harm reduction arguments are ambiguous. I find two completely different arguments at work, and liberals frequently conflate them. The two arguments have very different implications for who we should vote for.

I’ll call the two arguments Harm Reduction A (HR A) and Harm Reduction B (HR B). They go something like this:

HR A: It’s best to vote for the electable candidate who will do the least harm. In (almost) all elections, there are only two electable candidates: the Democrat and the Republican. We should vote for the candidate who will do less harm, compared to the other candidate.

HR B: It’s best to vote for the electable candidate who will do the least harm. In (almost) all elections, there are only two electable candidates: the Democrat and the Republican. We should vote for the candidate who won’t harm the world, compared to what it’s like now.

The Difference Between HR A and HR B

“But aren’t those the same argument?”

Well, no.

HR A is an argument about relative harm between individual candidates. It’s saying that we should compare the two candidates to one another and vote for whichever one will be less harmful. This is, of course, simply a repeat of the ‘lesser evil’ argument I wrote about earlier.

HR B, by contrast, is more an argument about absolute harm in the world. It’s saying that we should compare the two candidates to the world as it exists now and vote for whichever one won’t harm it. Thus minimizing harm.

HR A sets a lower standard. In elections where both candidates would harm the world, HR A recommends we vote for whichever one would harm it less. HR B, by contrast, recommends we vote for a third party candidate or not vote at all in that situation. HR B doesn’t require candidates to be perfect, but it does require candidates to not be bad.

Electoral Implications

And here we arrive at the big issue. The difference between the arguments is no hypothetical. Every presidential election since I was born has featured two major party candidates who would likely both harm the world. It’s all too real. The only differences between Democrats and Republicans at the presidential level concern how much harm they’d cause.

What this means is that at the presidential level, HR A recommends we vote Democratic. HR B recommends we vote third party, or not vote at all. The exception would be if Democrats (or, for that matter, Republicans) nominated a candidate like Bernie Sanders or someone to Sanders’s left. That sort of candidate would pass both standards.

Non-presidential elections are more complicated. Here the ‘harm reduction’ argument for Democrats is both stronger and weaker. Depending on the details. It’s stronger because members of Congress, and lower offices even more so, have far less potential to do harm. Electing a milquetoast Democrat to Congress may result in a vote against Medicare for All. But it won’t result in, say, a drone war.

However, it’s a weaker argument for Democrats because the Democratic candidate for Congress might not cause the least harm. Suppose, for example, the US has a Democratic President who’s very anti-privacy and pro-war (e.g., Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, et al.). Suppose, further, that the Republican candidate for Congress is very pro-privacy and anti-war. In that situation, HR A recommends you vote Republican for Congress. HR B might make the same recommendation.

It all becomes highly contextual.

Example #1: 2012 Presidential Election

Barack Obama’s first term in office was a mixture of good and bad, but mostly bad. The good is well understood. We all know about the Affordable Care Act, which led to historic drops in the uninsured rate. The Obama Administration made some strides on gender equity in wages. At a deeper level, the Obama Administration represented an accomplishment of representation and hope for black Americans.

These were all good things. But the Obama Administration also did a lot of bad things. For a start, the Obama Administration:

– Authorized more than 500 known drone strikes killing about 4,000 people.

– Managed wars killing about 75,000 people in Iraq and 25,000 in Afghanistan.

– Deported about 3 million people.

– Expanded the use of “secret laws.”

– Ramped up government surveillance and eroded privacy to an even greater degree than George W. Bush.

– Locked the United States into a 10 year, $38 billion military aid package to Israel.

The point here isn’t to argue that Obama was all bad or that the two parties are equivalent. He wasn’t, and they’re not (at least in the details).

The point is to show the divergence between the two ‘harm reduction’ arguments. Mitt Romney, Obama’s opponent in 2012, was a bit worse than Obama, on the whole.

If we had to rate every presidential candidate from, say, -10 (maximally harmful) to +10 (maximally beneficial), it would be fair to rate Romney about a -5 or -6 and Obama about a -3 or -4.

HR A would say to vote for Obama. HR B would say to vote third party or not vote.

Example #2: Christopher Peters vs. Dave Loebsack (IA-02 Congressional Races, 2016 and 2018)

I live in IA-02, where the GOP and Democratic candidate for Congress were Christopher Peters and Dave Loebsack, respectively, in both 2016 and 2018. Loebsack is something of a generic, centrist Democrat, and Peters is a very libertarian-leaning Republican with pro-privacy and anti-war leanings.

This is where contextual aspects come into play. In 2016, with Hillary Clinton likely to become the next President, HR A would’ve recommended a vote for Peters. He would’ve acted as the better check on Clinton’s pro-war tendencies. In 2018, with Trump as the President, HR A would’ve recommended a vote for Loebsack. Loebsack is the better check on Trump.

HR B is a bit less clear here, but I think the 2016 choice would’ve been Peters or third party, while the 2018 choice would’ve been Loebsack or third party.

Why HR B is Preferable to HR A

As it turns out, HR B tracks my own voting behavior rather closely. In the 2012 presidential election, I voted third party. In the 2016 Congressional election, I voted for Peters. And in the 2018 Congressional election, I voted for Loebsack. I find that HR B describes my reasoning process pretty well.

However, I think a lot of people, especially Democrats, go for something like HR A. Here’s why I think you’re wrong to do so: HR A sets a very low bar, and it allows for the Overton Window to continually shift to the right.

At some point, you have to ask yourself where to set the limit. How far would you go in voting for the ‘lesser evil’? Suppose the Republican presidential candidate advocates wars that will kill 5 million people, but the Democratic candidate advocates wars that would kill only 1 million.

HR A says you should vote Democratic in that election. But, really? Are you going to do that? How bad does it have to get before it’s unacceptable? Setting aside the more extreme example, the fact remains that continuing to vote for centrist Democrats gives the Democratic Party a blank check to continue moving to the right. As long as it stays a bit to the left of the GOP.

HR B gives us a good standard for where to set the limit: at 0 on a -10 to +10 harm scale. Don’t vote for anyone at -1 or below. That seems like a good standard to me, and if more people held to it, our politics would stop its continuous downward slide.

I’d rate Bernie Sanders about a 0 or +1 on the -10 to +10 scale. Consequently, I advocate the “Bernie Sanders Test” for 2020 Democratic candidates: to earn my vote, the Democrat needs to be at least as good as Sanders. Far from a ‘purity test,’ this is a test of basic, minimal decency. And, much more troubling for the Democratic Party, Bernie Sanders is once again the only potential candidate who passes the test, so far.

Limitations of Harm Reduction as a Democratic Argument

The implications of everything above should be clear enough. ‘Harm Reduction’ makes some sense, especially if you accept HR B. HR A is a pretty bad argument.

But ‘harm reduction’ doesn’t do the work Democrats want it to do. And it certainly doesn’t work as an across the board justification for voting Democratic. It requires careful attention to details, and it requires the Democrats to nominate a candidate for President who, for once, won’t harm the world.

In lower level races, harm reduction arguments often recommend voting Democratic. But sometimes they recommend voting Republican or third party. Consequently, it’s not a catchall argument for Democrats.

And so, alas, Democrats, there are no shortcuts. You’re going to have to fix the problems with your party.