Elizabeth Warren 2020 began in 2015. A coalition of liberals and progressives lifted her up as the right person to lead an electoral coalition. Why? Her bona fides as a consumer advocate and legislative leader – and her broad appeal across the Democratic Party – suggested her as the champion of a movement to push Obama’s Democratic Party to the left without leaving the Obama coalition behind.

Her 2020 campaign aimed to do just that. But the terrain changed. It was no longer a unity between Obama and the myriad forces of the shattered electoral left. It was a surging electoral left – united by the 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign – and the Biden/Clinton/Obama ‘party establishment.’ Warren promised to combine the progressivism of Sanders with the practicality of a campaign that could mobilize Democratic voters and win over a bit of ‘Middle America.’

Or so the theory went. We know it didn’t work out that way, and I’ll discuss why. Here are two major factors I see contributing to her loss. And one factor some Elizabeth Warren defenders cite that I’ll argue wasn’t really much of a factor.

1. Warren Didn’t Consolidate The ‘Progressive’ Vote

Pundits talk about electoral lanes, but we should be careful about that. Real voters are more complicated than analytical frameworks, especially ones built on the fly.

There are lots of ways we can think about the Democratic electoral coalition. Nate Silver’s 538 has, at various points, endorsed a ‘5 Corners‘ model or a ‘Six Wings‘ model. Those are mostly ideological and identity groupings. Other models turn on how well known the candidates are – established, like Joe Biden, or new, like Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar. And yet others carve the candidates into ‘electable’ and ‘non-electable,’ a hazy distinction that may or may not line up with the world in a meaningful way.

For my part, I work with something like the 5 Corners model in mind. But I also keep in mind it’s a division of convenience. The Democratic Party is huge and its coalition unsettled. No matter how we think about these things, one group of voters leans progressive and/or left. Any plausible road to the nomination for Elizabeth Warren started by consolidating these voters and locking them in as a mass base. She didn’t do that.

Defeating Bernie Sanders

About a year ago, I offered advice to each candidate. For Elizabeth Warren, I told her she had to defeat Bernie Sanders. Why? Sanders stood between Warren and consolidating the progressive vote.

Warren steadily rose in the polls from April through October, rising from sixth place to a close second. And this wasn’t a flash in the pan, like, say, Kamala Harris’s late June rise. She seemed to be getting somewhere.

Most Democrats like Warren, and she gradually won over the supporters of other candidates as they dropped out. I think she did especially well with former supporters of Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris, and Beto O’Rourke. She also built an impressive grassroots fundraising and mass mobilization model. She used all this to gradually convert skeptics into fans and fans into supporters.

It was great, except for one problem. None of this defeated Bernie Sanders. Warren gained wide support among Democrats, but she never gained the core base she needed – deep support among progressives. The closest she got to a core base was progressives with graduate degrees. Each major bloc of Warren supporters had a choice. Voters concerned about electability could choose between Warren and Joe Biden. Voters who wanted to elect a woman with a liberal voting record could choose between Warren and Amy Klobuchar.

Oh, and voters who wanted Medicare for All and other progressive ideas? They could choose between Warren and Sanders. Few, if any, voters looked at their options and concluded Warren was the clear choice.

Trying and Failing

It’s not that Warren didn’t try. She fought hard for the endorsements of progressive groups and the votes of progressive voters. And she had some successes. She won the endorsements of Ayanna Pressley and Julián Castro. Black Womxn For and the Working Families Party endorsed her. But Sanders won far more endorsements among Warren’s target base: Pramila Jayapal, Ro Khanna, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, Center for Popular Democracy, Democratic Socialists of America, Dream Defenders, Iowa CCI, People’s Action, Progressive Democrats of America, Sunrise Movement, and on and on.

Warren tried at various points to ‘out-left’ Sanders. She presented herself as Sanders’s ideological match, but pragmatic better. And then she pushed at the left edge on issues like student debt and the wealth tax. Sometimes even foreign policy. She combined this with issues – like impeachment – of more concern to wealthier, process-minded liberals.

The net impact of these efforts? Young and progressive voters at the Iowa Caucus and New Hampshire primary overwhelmingly preferred Sanders to Warren. And so, nothing worked for her. By January – once it was already clear her campaign was fading – she pivoted toward attacking Sanders. But it was too late. And her hard push for progressive backers left her with no backup plan in the event of failure.

2. Warren’s Medicare for All Pivot Didn’t Work

Elizabeth Warren wanted to be the candidate progressive enough for Sanders supporters, intellectuals, and social movements, but moderate enough to satisfy the party establishment, the media, and supporters of candidates like Cory Booker, Castro, and Harris. ‘Party unity,’ as she put it.

She won key endorsements from the New York Times and Des Moines Register. And the party establishment didn’t actively oppose her. No less than Harry Reid himself speaks highly of her. Why? Largely because they hate Sanders, and they knew Sanders could win. The specter of a Sanders nomination pushed Warren forward as the compromise candidate. Warren also did well with Booker and Castro – preventing Booker from endorsing Joe Biden and winning Castro’s endorsement outright.

But this road runs right through triangulation on Medicare for All, a rough road blowing out the tires of several campaigns. Most notably Harris’s. How did Warren play it?

Warren’s Views on Medicare for All

On paper, Warren endorsed Medicare for All until the end. But she announced a bad payment plan for it, and she said she wouldn’t pursue it as her first health care priority in the White House. Most political analysts – as well as progressive voters – saw this as an attempt to please both sides. Why? Because that’s exactly what it was.

It didn’t work. Had Warren defeated Sanders early and consolidated the progressive vote, it might have worked. Her triangulation on Medicare for All provided psychological cover to her progressive supporters. But voters who support the policy first and the candidate second switched to Sanders. Why? Because they still had Sanders as an option. Warren needed a progressive base with no alternatives before she made that kind of move.

For my part, I think Warren was always planning to pivot away to some degree from Medicare for All before the general election. But stalling in the polls, not defeating Sanders, and getting challenged by Buttigieg came together in such a way that she had to pivot earlier than planned. And the continuing strength of the Sanders campaign ensured it wasn’t successful.

Media Coverage and Medicare for All

Pete Buttigieg baited Warren on Medicare for All, and Warren took the bait. Did the media hold Warren to an unfair standard it didn’t apply to Sanders? Not exactly.

First, Sanders released funding ideas for Medicare for All well before Warren. He’s had a list of financing ideas for a long time. It’s schematic, but that’s normal for policy proposals. Single-payer health insurance is a normal idea in wealthy nations like the U.S., and there’s little reason to believe we can’t pay for it. What it lacks is political support. If we want something unworkable, we can check out UBI.

Second, this narrative was a consequence of the campaign Warren ran. She ran as a policy expert, as someone who ‘has a plan for that.’ This won support from highly educated voters looking for a policy candidate, but it left her susceptible to Buttigieg’s challenge. We might expect the person with a ‘plan for that’ to go above and beyond on proposals. By issuing an unfair demand, Buttigieg skillfully exploited a weakness in Warren’s campaign.

Third, Warren’s plan wasn’t any good. Medicare for All requires a broad tax base for both financial and practical reasons – i.e., it’s much easier for wealthier people to roll back benefits if they’re the only people paying for them. But since Warren is a progressive who believes in means-testing and process reform, she couldn’t ask middle income people to pay for good services. It violates her ideology. Sanders, as a social democrat, is willing to ask middle income people to pay for good services.

And so, Warren’s plan was impossible to implement. She took a hit to her credibility as a policy expert. As a result, Sanders gained ground on the left and Buttigieg and Klobuchar gained ground elsewhere.

A Non-Factor: Media Bias

Media bias always factors in to the way we talk about campaigns, and I’ve addressed it before. As a broad issue, there’s little basis for claiming media bias cost Elizabeth Warren a win. Why? She received more coverage than Buttigieg and Klobuchar throughout the campaign. And her coverage was more positive than the stuff directed at Klobuchar and Sanders. So, I’m not going to rehash the issue here.

But there’s a narrower claim some Warren supporters pushed more recently. The idea is that media bias against Warren in February cost her the positive media coverage she should’ve received for her (allegedly) strong finish in Iowa.

It’s easy to dismiss this as Warren supporters grasping at straws. Or as processing of a loss. And some versions the claim claim really are just that, e.g., the version in The Week.

‘Warren Erasure’: The Argument

Joan Walsh argued in The Nation that the media ‘erased’ Warren after Iowa. Some Warren supporters took up the idea of ‘Warren erasure’ and ran with it.

Let’s look at that. Walsh gave two reasons why Warren should’ve gotten positive coverage from her Iowa results. The first is that she overperformed the polls. The underlying set of assumptions here is that doing better than one’s polling is a mark of beating expectations, and beating expectations merits positive coverage.

The second is that there are typically ‘three tickets’ out of the Iowa Caucus. The idea is that the press awards a ‘success’ badge to three candidates. Given that Warren finished third and overperformed her polling, she should’ve gotten one of the three tickets. However, the press only awarded badges to Buttigieg and Sanders. Therefore, the press failed to give Warren her due.

A Quick Note on the Complexity of ‘Bias’ Claims

Here’s a starting point. Even if everything Warren defenders assert is correct – and it isn’t, but I’ll get back to that – it wouldn’t establish that the press was biased against Warren. The biggest story in Iowa was the uncertain results and confused counting process. Since that story related to the winner of the Iowa Caucus, and only Buttigieg and Sanders had a chance of being that winner, the press focused on Buttigieg and Sanders. That’s just normal journalism. It’s how journalists handle surprise changes in the story, and it’s no reflection of bias.

Had the press set aside these issues to write puff pieces on Elizabeth Warren, Buttigieg and Sanders would’ve complained about bias in her favor. And they’d have been right to do so.

Three Tickets?

But let’s get back to the argument.

It’s easy to dismiss Walsh’s second point, the one about ‘three tickets.’ Walsh is correct that the ‘three tickets’ claim is a piece of conventional folk wisdom in politics. But it’s wildly inaccurate. In thinking about it, I struggle to find a case when the press has ever issued three tickets out of the Democratic caucus in Iowa. It certainly didn’t in 2016, when there were only two serious candidates – Hillary Clinton and Sanders. It certainly didn’t in 2008, when Clinton and Barack Obama were the only viable candidates. Nor did it in 2004 – John Edwards and John Kerry – or 2000 – just Al Gore.

And so, people say there are ‘three tickets.’ But the evidence suggests otherwise, as some outlets have argued for more than a decade.

Overperforming the Polls?

That leaves us with the claim that Warren overperformed her polls. Did she? The brief answer: sort of, but it doesn’t support the claim Warren should’ve received positive coverage.

We can look at this in terms of standing or raw numbers. In standing, Warren was in a statistical tie with Pete Buttigieg for third place in polling averages. They were about 7 points behind Bernie Sanders. In the best poll – Ann Selzer’s Iowa Poll – Warren was in second. She finished third, about 6-7 points behind Sanders. So, Warren finished right where the polls suggested she would.

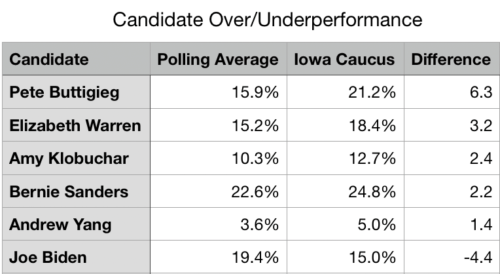

But Warren supporters point to the raw numbers. She won a higher percentage of the popular vote than the polls predicted. That’s true, but so did everyone else not named Joe Biden. Here’s a table showing the polling averages and final popular vote, with a note at the end showing the difference between the one and the other.

Not much stands out here. Only Buttigieg’s solid performance and Biden’s terrible one. Polling showed about 10-15% of the electorate undecided or choosing obviously non-viable candidates. Distributed across major candidates, you’d expect each to pick up about 2 or 3 points from their polling levels. And with the exception of Biden – for the worse – and Buttigieg – for the better – that’s exactly what happened. Nothing in these data suggests the media robbed Warren of positive coverage.

Cause and Effect

In its silliest versions, the ‘Warren erasure’ argument appeared as a broad campaign theme. The argument here is that lack of media coverage caused Warren’s collapse in the polls in the last couple of months of 2019. A few Warren supporters provided various conspiratorial reasons why the media allegedly did this.

I’m hesitant to respond to this kind of foolishness. But it’s easy to refute. Warren’s decline in the polls started about a week before the October 15 fourth Democratic debate. It accelerated after that debate. But her high levels of media coverage continued through the end of October and probably well into November.

The obvious conclusion here is that Warren’s decline in polls caused any decline in media coverage. Not vice-versa. Things that happen later don’t cause things that happen earlier.

The Final Months of the Elizabeth Warren Campaign

Elizabeth Warren began sliding in the polls in October, and she never stopped. As a result, the last few months of the Warren campaign looked much different from the early ones. Starting in the middle of January, Warren: picked a feud with Bernie Sanders, announced a new and implausible student debt policy, released a likely unconstitutional plan to punish electoral disinformation campaigns, pandered to anti-Medicare for All union leaders, reversed her opposition to Super PACs, hilariously and effectively criticized Michael Bloomberg at the Nevada debate, and then trolled Bloomberg afterward.

So, that was weird. What happened?

Warren’s slide in the polls stalled her fundraising operations at the same time she was spending tons of money on ground operations for the March and April states. By the end of January, she was almost out of money. Literally. Her FEC filing at the end of January showed her with less cash in hand than all the major candidates, putting her in Cory Booker territory. Going on a spending spree in the later states was a bold strategy, and it didn’t pay off for her. She wasn’t competitive long enough for the ground game in March and April to matter.

But – more important for present purposes – this explains why Warren’s campaign got gimmicky. It helped bring her fundraising numbers back up. However, it didn’t help her win delegates.

The End of Elizabeth Warren 2020

The Elizabeth Warren campaign held promise. She entered the race with a compelling case – a progressive policy slate with the expertise and problem solving skills to get it done. Or, as I put it, ‘capitalism’s heart surgeon.’ She also skillfully navigated the issues facing any woman running to be the U.S.’s first woman president, embracing issues impacting women without reducing her campaign to gender in the way Kirsten Gillibrand did.

In the end, it didn’t work. Why? She never found a mass, loyal base among Democrats, and she didn’t win one among independents or new voters, either. Her core appeal was limited to people who like very progressive policy ideas but aren’t comfortable with working class or movement politics. Demographically, her support was heavily concentrated among voters who were both very progressive and very highly educated. And when she tried pivoting to the center – in the way all conventional politicians do – she lost half her base without picking up anyone new. She united the party so well, in a sense, that her supporters didn’t mind voting for…other Democrats.