Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term ‘intersectionality‘ in 1989 as she used the central metaphor in a paper in a law journal. Crenshaw used the term to pick out the idea that people’s identities overlap to create novel experiences. As a legal scholar, she drew attention to experiences of discrimination. For example, black women may face novel issues neither black men nor white women face.

Since then, the term – and perhaps also the idea it picks out – took on a life of its own. It’s a rallying cry for some social justice movements. People routinely assert things like ‘the future is intersectional.’ Politicians run (usually unsuccessful) campaigns around it. But as leftists, what does intersectionality mean for us? Is it a tool for getting things done? A theory we should accept or reject? How should we handle it?

The Background of Intersectionality

So, Crenshaw coined the term. But it’s less clear whether she coined the idea or just the name. Of course, a name isn’t just a name. I argued as much in my first book. By providing a central metaphor, Crenshaw – at a minimum – transformed the idea.

Intellectually, W. E. B. Du Bois laid much of the background. By the 1940s, Du Bois argued that the race and class system intertwine. Much earlier – as early as the 1900s and as late as the 1930s – Du Bois had argued for the race–identitarian thesis that posited race as the central driver of society. He replaced that view in the 1940 work Dusk of Dawn with something much like race and class intersections.

Much later, Crenshaw coined the term ‘intersectionality’ in the context of critical race theory. These theorists see racism as embedded deeply within American society, not merely in the law. Racism thrives in American literature, languages, et al. Critical race theorists find these embedded kinds of racism to be the real driver of white supremacism. And they often see white supremacism as the major driver of U.S. society. Embedded racism thus drives white supremacism and the U.S. as a whole.

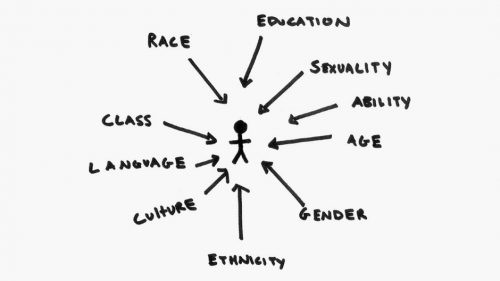

Crenshaw added intersectionality to the basic tenets of critical race theory. She points out that race doesn’t act alone. It comes linked to other systems of oppression – gender, class, sexual orientation, et al. Thus, Crenshaw accepts intersectional-identitarianism, not race-identitarianism. For Crenshaw, identity categories as a whole system form the basic structure of society.

A Theory or a Method?

‘Intersectionality’ serves both political and intellectual functions. But the literature remains ambiguous on whether it’s a theory or a method (or both). A view about how identities combine within new forms of oppression? Or a way of thinking about identity and oppression?

I find that it can be both, but it should be a method rather than a theory. As a method, it teaches us a lot about how identities remain in flux. They change quite a bit both over time and across groups today. I’d recommend to readers Catharine MacKinnon‘s explanation of intersectionality as method. We might also ask Crenshaw herself! Unfortunately, Crenshaw – usually a very clear scholar – writes less clearly on this issue. She calls it a method and a tool for action. But she calls it a theory in the subtitle of the same article.

But standard descriptions of intersectionality call it a theory rather than a method. Why all the confusion?

Here’s what I think is happening: Intersectionality is a method, not a theory. The theory part is critical race theory, which formed a key part of its history. Intersectionality doesn’t require critical race theory, but that body of theory made its intellectual home. The problems with intersectionality – the tendency of its practitioners to lean on bad theories like identitarianism – happen where it leans closest on critical race theory.

Intersectionality and Class

When listing the identities that intersect, people usually include ‘class.’ Regular readers are surely familiar with my view that class isn’t an identity, and therefore shouldn’t be included on a list of intersecting identities. What’s happening here?

When intersectionality theorists (or ‘methodists’?) include class, they define it in socioeconomic terms, not Marxist terms. They think about class in terms of, e.g., education, income, or wealth. Sometimes they think about it in cultural terms, e.g., personal identification with working-class culture, rural culture, ‘middle class,’ and so on. They don’t talk about it in the Marxist terminology of relationships with structures of economic ownership and control. For example, intersectionality theorists might discuss the social status of black women with a college degree who earn about $75,000 per year. But they don’t discuss the social status of black women who do contract work for large companies. At least not directly.

To be clear, discussions about the intersections of race and class in the Marxist sense – or perhaps the Weberian sense – aren’t absent from the literature. You can find it. See E. Franklin Frazier’s classic book Black Bourgeoisie for one example. Or see C. L. R. James’s classic on the Haitian revolution, The Black Jacobins.

It’s just that these books don’t come from intersectionality theorists specifically or critical race theorists in general. The closest we find is black feminists working in Marxist traditions. See, for example, the work of Patricia Hill Collins. Black Feminist Thought remains the best place to start. But, for Collins, intersectionality isn’t a theory and it doesn’t come embedded in critical race theory. It’s a method to use while applying Marxism to the intersection of black women and work.

Intersectionality, then, should be a method for working identity into leftist projects where class still plays the underlying, fundamental causal role.

Applications

What does all this mean for leftists? We should use intersectionality as a key method. We can and should adopt intersectional approaches. Working-class people have wildly different experiences depending on gender, race, sexuality, et al. And this means they have differing struggles in some cases.

At the same time, we should avoid common errors when combining intersectionality with critical race theory, e.g., the reduction of society to identity categories, excess focus on culture, literature, psychological bias, et al.