What are people looking for when they’re thinking about ‘summer reads’? How about you? It seems like most people take it to mean adventure stories or books to take with them on vacation.

I guess there’s some of that in my July list. But I can’t say I have anything too specific in mind when I’m talking about the summer. I suspect my summer reading isn’t that much different from other parts of the year.

Without further ado…

Miguel Cervantes – Don Quixote

Maybe we could call Don Quixote a summer read? It’s one of the most influential works of literature in history! Probably most Americans know at least a bit about it. You know, the knight who fights windmills? Few of them ever read it, though.

So, why not? I read it. At least, I read the first part of it.

And it was fine. I read it as a satire of chivalry, but there’s an entire body of literary criticism that interprets it in other ways. So, I can appreciate the book for its nuances and various uses. But I wasn’t really the book’s biggest fan.

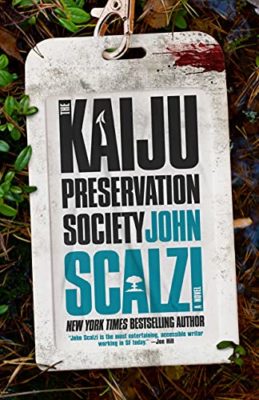

John Scalzi – The Kaiju Preservation Society

Look at that – Scalzi wrote a new book! And he set it during the early pandemic in New York! What’s not to love?

For anyone not familiar with Scalzi, he’s one of the best new sci-fi authors of the last 20 years. He often writes in roughly the tradition of Heinlein and military sci-fi. And, if anything, his writing is even more accessible than some of the easiest authors to read.

Is this book one of his best? No. It’s just a good, solid story.

Science Fiction Writers of America – The Science Fiction Hall of Fame

So, the SFWA put out a collection of the greatest science fiction short stories from the late 1920s to the early 1960s. It has all the authors anyone familiar with this time period might expect. For my part, I think ‘Nightfall’ by Isaac Asimov is the best story from this time period. And the SFWA voters agreed. It’s in there.

And so are lots of other excellent stories. Are some of them dated by now? Of course. But lots of truly great sci-fi stands up well, even 60-100 years later.

Ronald Grigor Suny – Stalin/Isaac Deutscher – Stalin

It’s tough to find a good biography of any Soviet leader. Especially Stalin. I found not one, but two! Most of the ones available either come from fawning fans of Stalin or (more commonly) hardened enemies. But both of these books work for anyone looking for something accurate and insightful.

Suny focuses on the years before the October Revolution, while Deutscher covers through the end of World War II and beginning of the Cold War. Suny began writing in the late 1980s. But he relied so heavily on the newly opened Soviet archives that it took him more than 30 years to bring the book to print.

Suny sees Stalin move from a young Georgian nationalist in rural poverty to a Bolshevik internationalist and communist. And he tells the story of how Stalin became the political operative the world knew in the 1920s and later. It’s difficult to understand how Stalin became the kind of person he showed the world in the 1930s. How does one preside over something as awful as the Great Purge? Suny gives it his best shot. And then he ends the book with a satisfying account of the October Revolution from Stalin’s perspective.

Deutscher wrote far earlier – the late 1940s, while Stalin still lived. His book is worth a read for its own reasons. He provides a critical analysis of Stalin free from much of the Cold War baggage that would come only later.

Amia Srinivasan – The Right to Sex

So, we have another entry in the category of ‘philosophers writing books for a popular audience.’ Like many of these books, Srinivasan takes on a large and ambitious project. But I think she accomplishes much of what she sets out to do. More than anything, she brings a fresh perspective to well worn debates.

I appreciate that. In The Right to Sex, she tackles issues of sex and gender, pointing out many of the ways public discussion tilts toward the perspective of men (and white women). She does this for a wide range of issues: sex and consent, porn, incels, campus harassment, and crime and punishment.

As she explains her central question in the coda to the title essay, she wants to ask how we can engage in a political critique of personal desires without lapsing into either the language of (male) sexual entitlement or moral authoritarianism.

It’s a tough question. And it’s one we see in different forms not only all over debates concerning sex, but also within leftist circles more broadly. Indeed, Srinivasan ends the book with an attempt to get at broader leftist debates over class reductionism and identity politics. That part is all too brief, but the application is an important one.