Okay, so summer’s heating up by the point, and we’re halfway to the end of the baseball season.

Of course, I do have a baseball book on the list this month. Because why wouldn’t I? Mostly, though, I’ve got some history for you.

Polymnia Athanassiadi – Julian / Rowland Smith – Julian’s Gods

So, I read two books on Roman Emperor Julian, the last pagan emperor. These days, he’s best known as the ‘Julian the Apostate’ of later antiquity who tried (and failed) to stem the tide of Christianity and conquer Persia.

In terms of approach to Julian, Athanassiadi pushes back against the claim that Neoplatonic philosophy played little role in Julian’s policies and worldview. Meanwhile, Smith defends a more traditional view of Julian as political actor rather than philosopher-king.

Athanassiadi sees Julian as an intellectual within a united Hellenistic and Roman state. And she takes Neoplatonism as the center of a unified Greek philosophical tradition that holds it together – minus, of course, Greek philosophy’s Epicurean and Pyrrhonian skeptic components. To this, Julian added Mithraism to create a viable alternative to a Christian Empire.

Why think this? She cites Julian’s classical education and the horrors of watching Constantine – the first Christian emperor – murder most of his family. And she confirms it by citing Julian’s writings. With the chance to apply those writings as the ruler of the state, Julian attempted to restore cities and local government with a unified, civic pagan religion.

As for his ill-fated Persian invasion, Athanassiadi chalks it up to a series of errors Julian committed in heavily Christianized Antioch. His hubris, above all, did him in.

At one level, Smith’s book combines an assessment of Julian’s work with a focus on his religious beliefs. And at another, he attempts to counter Athanassiadi by arguing that Julian was much more eclectic than a mere Neoplatonist. Smith thinks he combined a broad range of cultural ideas.

He likewise argues against the centrality of Mithraism to Julian’s thought. Instead, Smith thinks Julian, to some extent, experimented widely in his search for alternatives to Christianity.

I think both books have their merit. I appreciate Athanassiadi’s deeper analysis of Julian and the Greek philosophical and pagan traditions. At times, though, Smith’s book seems better grounded in historical research.

Keith O’Brien – Charlie Hustle

And of course we need a summer baseball book in the list!

This recent bio of Pete Rose from Keith O’Brien tells the story of Charlie Hustle himself, from his young days as a poor boy in Cincinnati, all the way through his years as a hometown hero and his disastrous fall and banishment from baseball.

O’Brien tells the story well. He does an especially nice job laying out the complexities of Rose’s popularity with the working-class Midwest in the 1970s and 1980s. Yes, Rose was a great player. And yes, he did earn his reputation as a hard worker. At the same time, Rose appealed to down on their luck whites who wanted a white hero. Therein lies many of the thorny issues.

Contrary to some of the criticism of the book, I think O’Brien does a fair job getting at Rose’s personal flaws. His gambling and drinking cost him, both as a person and a baseball player. And while we can reasonably criticize MLB for its decision to keep Rose out of the Hall of Fame, Rose mostly did it to himself. O’Brien never forgets that.

I’d recommend this book to anyone looking for a historical perspective on Rose and his era, as well as on the dangers faced by baseball in our current times.

Mike Duncan – Hero of Two Worlds

Mike Duncan – of Revolutions podcast fame – published a bio of one of the key figures of multiple revolutions.

Americans may know the Marquis de Lafayette as a hero of the Revolutionary War. Or just as that dude who got everything in the U.S. named ‘Lafayette.’ But the French know him as a key player in their revolutionary period, from the end of the Bourbon monarchy to the July Revolution of 1830.

Duncan provides a satisfying account of Lafayette’s life and times. He excels at building a narrative and telling a complex story about Lafayette and his motivations. Positioned between conservative royalists and radical republicans, Lafayette advanced a mostly consistent politics in a very turbulent era. And he did so both in the U.S. and in France.

As far as popular history writing goes, Duncan is one of the best. Readers should check it out, as it also provides a key overview of the basis for revolutionary movements throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

E. Franklin Frazier – Black Bourgeoisie

In this 1950s sociology classic, Frazier takes aim at the ‘black bourgeoisie.’ He uses the term to pick out the ruling elite of black society, rather than the sharper Marxist usage aimed at local managers and small business owners. Frazier identifies this elite as a range of basically ‘middle class’ black Americans, such as physicians, lawyers, white-collar workers, and small business owners.

Frazier sees in this group a self-loathing, along with a dislike of working-class black people. And he thinks the black bourgeoisie draws all this from centuries of racist history. Frazier thinks they use exaggerated myths of the power of black business – as well as the potential to build an alternative black economy – as a way to cover over these feelings of inferiority. And they use conspicuous consumption as a way to compensate for it.

It’s a harsh lesson, and Frazier documents it thoroughly.

In many ways, the book is obviously dated. Not simply in time, but also in approach. Frazier could’ve done more to recognize the power of members of his target group to reject these assumptions and choose a more productive path. He also delves into casual misogyny and homophobia, which were typical at the time of writing.

That said, Frazier makes a number of important points. Ones that will sound familiar to anyone who studies middle class people and tastes. And so, he didn’t exactly miss the mark, either. Frazier often comes off as perceptive and insightful, at least when thinking about a critical mass of the middle class.

There’s a reason people still read him.

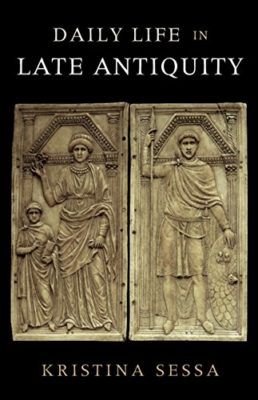

Kristina Sessa – Daily Life in Late Antiquity

As I read this book, I thought to myself: why don’t more people write books like this one?

Sessa covers life in the late ancient Roman world, roughly from the 3rd through the 6th centuries. That’s not new. But she covers it from the perspective of ordinary people. She hits rural and urban life, the everyday household, the state, the medical establishment, and religion. Along the way, readers gain a much more vivid picture of that world that they gain from, say, a political or military history.

So, I learned a lot from this book. The sections on ancient medicine and rural and urban life proved especially valuable. That said, the book can necessarily be quite vague at times. Evidence for the period isn’t always that great. But Sessa stays up front and forthcoming about that.

She succeeds at what she sets out to do.