Readers who followed along with my posts on turning 40 already know some of what I’ve been reading lately. But, thankfully, it’s not all about getting old. I’ve read some other things, too!

Continue along to find out what that might be.

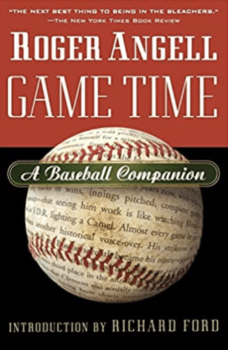

Roger Angell – Game Time

Here we’ve got a collection of essays on baseball from Roger Angell, who’s been writing about the topic since around 1960. He shared with us everything from conversations with Ted Williams and other old-timers to end of season summaries all the way into the early 2000s.

So, there’s a lot here. My favorite season summary is the one he writes for 1991. It includes a discussion of the pitching of my distant cousin in the NLCS.

Overall he brings to his essays a style at once both readable and engaging, and also analytical and insightful. I had a lot of fun reading these essays, even when the immediate context was lost to the distant past.

Catherine Cerveny – The Rule of Luck

This book is the first in a sci-fi/romance crossover series. Going in, I thought it had potential. But while I still see that potential, I just didn’t like the book. So, I won’t be reading the rest of the books in the series.

The basic premise works well enough. About a thousand years in the future, a ‘benign’ authoritarian government rules humanity. We survived climate disasters and multiple world wars, and we followed up on that by creating a big tech society where people live long and directionless lives. The main character runs a small Tarot card reading shop, and her love interest is a mobster fighting over a human genetic predisposition for luck.

Not a bad start. Ultimately, though, the romance part of the book falls flat for me. Maybe I just don’t like the genre. Maybe this book just wasn’t a good example of it. It’s hard for me to say. Either way, I found the ‘sexy’ scenes so off-putting that it knocked me out of my interest in the story.

Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington – The Big Con

Mazzucato and Collington do not like the consulting industry. That much is clear. They offer a systematic critique of that industry. Not due to political or moral concerns. Rather, they argue that the consulting industry, for the most part, doesn’t actually deliver what it promises. Furthermore, they charge the consulting industry with relieving both private industry and government of their own internal capacities to do things.

How does the consulting industry do this? They do it via the ‘big con.’ In short, the consulting industry operates not by delivering value to companies – or by explicitly tricking them – but rather by creating the impression of delivering value. The industry speaks confidently to businesses and uses recycled ideas and slide decks. It operates low quality research institutes that generate confidence in its abilities. And it plays to managerial insecurities and desires for control.

Furthermore, by scooping up lots of work that companies and governments used to do for themselves, the consulting industry saps those companies and governments of their own experts and expertise. Governments that used to be able to provide services now farm those services out to consultants. Companies that used to source ideas from their own employees now farm out strategy to the ‘experts.’ And when things go badly, they can no longer do anything about it themselves.

Overall, Mazzucato and Collington present a compelling case. At times, they rely too much on individual scandals within consulting companies rather than the broader picture. But I think the overall landscape they paint is an accurate one. The question is what governments and companies should do about it.

Edward J. Watts – City and School

Back in the early 2000s, I took a course on the fall of the Roman Empire taught by Watts at Indiana University. So, I was excited for this book!

Watts discusses the role of the educational system in the life of the late Roman Empire. He focuses on two cities: Athens and Alexandria. The educational system, not unlike the contemporary U.S., provided the late Roman world with a common basis of skills and job training, a network of contacts, and an underlying code of culture and behavior.

In his chapters on the Athenian system, Watts tells a story about a largely pagan educational system and its challenges in an increasingly Christian world. Despite these challenges, the pagan teachers of Athens did quite well until the 6th century. They became pillars of their community, funding civic projects and taking on administrative roles in the city. And they fulfilled the desires of students for more spirituality by turning to Neoplatonic philosophy. Watts tells a story about how infighting and political missteps cost pagan philosophers this world, culminating with the closing of the Athenian Academy in 529.

In his chapters on Alexandria, Watts traces an emerging split in Christianity between intellectual traditions and asceticism. A backlash against philosophy by Christian leaders eventually led to the subsumption of pagan philosophy in Alexandria into Christianity. Watts interprets Christianity as sympathetically as possible, but it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that Christian extremism was the main problem here.

Watts discusses his sources carefully and presents a plausible account. Insofar as I might quibble, I think he overstates the role of Emperor Julian in ‘encouraging’ a Christian reaction that would’ve happened anyway. And his blaming of the closing of the Academy on internal forces stands in tension with the much more restrictive anti-pagan laws of 531.