Welcome to the first summer edition of the reading list for 2024! What am I reading this summer? So far, it’s been an eclectic mix, as you’ll see.

Read on to find out. And, of course, let me know what’s on your book reading mind!

Hugh Elton – The Roman Empire in Late Antiquity

I set out recently to read a few key books on the history of the late Roman Empire. And if nothing else, Elton’s book has the merit of, for the most part, hitting the right time period.

Elton argues that a few common features define the late Empire – a centering on the person of the Emperor and meetings with his court as a way to run state affairs, the Emperor’s building of consensus among key sectors of the aristocracy and the people, and a common set of issues handed to the Emperor by the earlier Empire. In short, the late Empire was not a time of great new problems that the Empire hadn’t seen before.

That’s quite a contrast to earlier theories that posted large, new problems in the late period.

I think Elton usefully explains the collapse of both the Western Empire (in whole) and Eastern Empire (in part) as a result of divergent interests between the Empire as a whole and the local aristocracy. In short, it made sense for local aristocrats to oppose imperial interests. At times, they even allied with ‘barbarian’ invaders.

That’s quite a danger.

Henry Mintzberg – The Nature of Managerial Work

This is an early 1970s classic, one of the first comprehensive empirical approaches to questions about what managers do all day. Mintzberg opposes theorists like Peter Drucker who write more from the perspective of management.

Mintzberg finds common features among managers at all levels, from foremen or line managers all the way to VPs and CEOs. In getting there, he divides management into interpersonal, informational, and decisional (sic) roles. Managers divide their time unevenly across these roles, and they’re torn between the many parts of their jobs. But they spend most of their time in meetings. And they put in long hours.

I think the basic picture still works today. Of course, we now need to account for modern changes, e.g., the rise of email. And I think Mintzberg also presents us with a basic blueprint for what a democratic, socialist system of management might look like.

One final note is that Mintzberg asks whether we can automate manager roles. He concludes that we can’t, due to the complexity of the job. But Mintzberg surrenders too easily here to the management perspective. Ultimately, managers control whether we can automate management jobs. And they say ‘no.’ Big surprise. We’d hear a different story if workers decide.

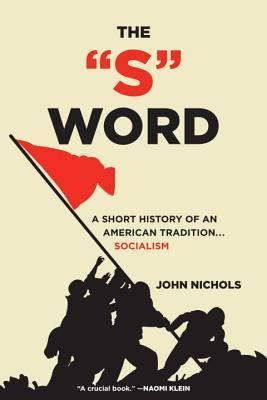

John Nichols – The “S” Word

Nichols wrote this book a bit over 10 years ago. And he situated socialism within U.S. history and traditions. He argues, convincingly, that socialism influenced many American political ideas. He presents socialism as something that’s as American as apple pie.

Yeah, maybe. As intellectual history, Nichols delivers a good book. I learned a few things from his discussion of Thomas Paine and A. Philip Randolph, in particular.

That said, the book is quite dated. Nichols’s discussion of contemporary politics probably worked well enough in the early 2010s. But it falls flat in 2024. And to get to his point, Nichols stretches ‘socialism’ way past its breaking point. It all rings as very pre-2015 ‘Old Guard‘ DSA, including progressives and radical (and even non-radical) liberals under the big tent.

Is it worth reading now? For a reader looking to situate U.S. socialism within U.S. history, sure. For a reader looking for a guide on politics today and in the future? I’d say pass.

Susan Pinkard – A Revolution in Taste

In this nifty little history of French cuisine, Pinkard traces a revolutionary shift over the course of the 17th century. And since the cuisine of France is so well known – the balance of delicate, complementary flavors – this comes as a surprise to the reader. As Pinkard tells it, a distinct cuisine arose from hundreds of years of contrary history.

On Pinkard’s view, French cooking once emphasized the creation of complex, multi-layered flavors that blend together into a uniform taste. This puts it much in line with Europe all the way back to ancient history, as well as much of the modern world (South Asia, East Asia, much of South America).

Why did this shift happen? Pinkard identifies economics and conspicuous consumption. In the 17th century, spices that once served as markers of wealth became more common. In response, the wealthy shifted to things that were more difficult to find, such as rare, in season produce.

We can see a similar trajectory in the 20th century with the TV dinner. Now cheap and a marker of working class status, it was once relatively rare and popular among the upper middle class.

With that said, I think Pinkard could’ve done more to emphasis the rise of the French style among the bourgeoisie. Pinkard sees bourgeois cuisine as a spinoff of the new style, though I think the evidence she presents suggests the same underlying forces (i.e., changes in the French economy) drove both trends.

Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò – Reconsidering Reparations

Táíwò defends a new approach to reparations, billing it as a constructive project rather than one based on the repair of harm. For Táíwò, we should pursue reparations to create a just world via addressing historical injustices and their legacy.

He’s a philosopher, and as a philosophical account, it works well enough. Táíwò employs the notion of distributive justice to argue, e.g., that rich nations should pay up. And he provides a valuable overview of the history of many of the injustices he cites.

That said, I don’t think it works as a political project. As with other moralistic projects, it appeals mostly to ultra-progressives. Including climate change merely doubles down on the problem.

The first problem with the political project Táíwò defends is that wealthy nations and people just aren’t going to do it. Maybe they should. But they won’t. And Táíwò has no coalition or political vision to make them do it. And second, Táíwò’s grounding of injustice in colonialism doesn’t really work. Colonialism is key, but it’s not foundational to the problems Táíwò discusses.

I think a better account of reparations would treat it as a supplemental project – aimed at truth and reconciliation – within a broader socialist vision.