In a review of the 2020 Thomas Frank book, The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism, Erik Baker lays out a basic progressive theory of the electorate. I’ll set aside, for the moment, the tension between that and the title of this post. Many leftists, after all, still identify as progressives.

It so happens I recently wrote a post that touched on this idea, in part. Here I’ll briefly sketch out Baker’s critique of Frank and why it’s so important for leftist electoral projects.

Baker and Frank

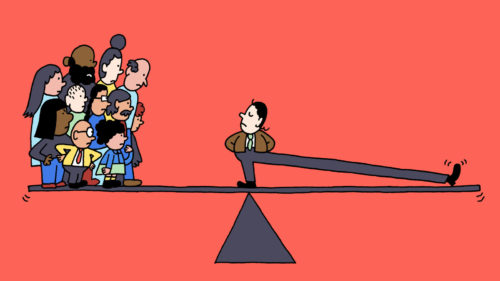

First, let’s look at Frank’s theory of the electorate. Frank – at least, according to Baker – claims there’s a latent social democratic majority in the U.S. This majority loves (or would love) ideas like the Green New Deal or Medicare for All. However, social progressivism and cultural issues turn them off. Elites turn them off.

That’s the idea.

While Baker places this view first and foremost with outlets like Chapo Trap House, Katie Halper, Michael Tracey, and assorted slices of the Bernie Sanders bloc, he also finds it in Frank’s book. As well as in his total oeuvre, for those of us who read ‘What’s the Matter with Kansas?‘. I know I did.

According to Baker, the theory misses why conservatives succeed. They don’t dupe rural people or working-class people by luring them with social conservatism. Rather, they present social and economic conservatism as part of a single package. They meld it together. They do so with popular attitudes like individualism, liberty, freedom, and so on. Conservatives present this to people as a core part of both their social and economic outlook.

And so, the left can’t just drop social democracy on people and hope for the best. We can’t just launch Medicare for All and then watch the votes roll in. Rather, along with it, we have to tackle all sorts of intersecting issues of race, gender, and culture. Baker also points out that even progressives tend to focus too much on elite discourse. They do so by, e.g., adding ‘class’ to diversity lawn signs instead of doing the hard work of organizing in working-class communities.

Baker again points out that the left succeeds – builds a ‘multiracial working class’ – only when it does real organizing.

The Left’s Addiction to Shortcuts

This obviously allows me to return to one of the central themes of my posts on leftist electoralism. Various factors – the urgency of the climate crisis, lack of leftist electoral success, lack of ready-made chances to plug in to good organizing efforts – drive the left to constantly, relentlessly seek shortcuts.

The theory of the electorate Baker sketches out is a product of this constant search for shortcuts.