After the 2004 US election, pundits – and college students like myself – went looking for answers. How could Americans re-elect a buffoonish warmonger like George W. Bush? Over the course of a decade, this search guided me from pundit-generated pablum like ‘NASCAR Dad‘ to the philosophically compelling ‘looping effects of human kinds’, as Ian Hacking put it. Let’s trace that journey.

What struck me about the punditry is their attribution of an ordinary event – the re-election of a president – to hidden, mysterious forces. Who were these NASCAR Dads riding to Dubya’s rescue? As it happens, they’re no one new. Lifting up the hood reveals the same white, mostly male, non-college educated voters who elected Reagan in 1980 and Trump in 2016. They vote Republican in every election. ‘NASCAR Dad’ is only a seemingly fresh take on an old story, loaded this time with cultural references.

But I drew lessons from getting burned by bad punditry and bad political science. Through works like ‘Making Up People‘ and The Social Construction of What?, I found philosophers doing great work on classifications of people and how people react – the ‘looping effects’ of my title! And so, I’ll start there. What are ‘looping effects’, and how do they apply to the term ‘bisexual’? Does it mean people aren’t really bisexual, just as people aren’t really NASCAR Dads? Or are NASCAR Dads real after all? Is there some ‘authentic self’ prior to how we’re grouped?

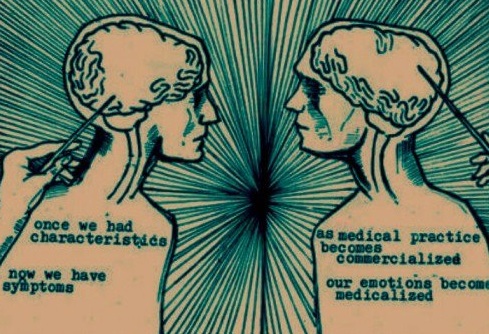

The Looping Effects of Human Kinds

Hacking’s work on looping effects seems deceptively simple. When people classify things in the natural world, the natural world doesn’t change. Call a tree an ‘oak tree’ and call a rock an ‘igneous rock,’ and it goes right on being the same tree or rock.

But call a person a ‘teen mother’ or ‘refugee,’ and it sets things in motion. One, the person might change. She thinks about herself as a teen mother or refugee, and then she behaves differently. Two, other people might act differently around her and change her in the process. Social systems – from friends to non-profits to legislatures – do things, from offering support to providing services to passing laws. And three, it generates and changes other classifications. Once we have a term like ‘refugee’, we might need new terms like ‘child refugee’, et al. More interesting than what happens when we classify trees and rocks!

Of course, it’s not always so simple. Trees and rocks might not just be trees and rocks. Scientific tools, instruments, organizations, et al. modify the world in lots of ways. Science studies researchers work on many of these issues. But the distinction holds up well enough for our purposes.

Hacking wrote about the first type of impact, where people self-apply classifications. I’ve done work here too, focusing more on the second and third types. But let’s talk about Hacking for a bit. He points to a feedback loop between the classification of a person and the person the classification picks out. We see how people classify us, and then we think about it, try it on, react against it, and so on. It changes us, and so the classification changes in response. The cycle continues.

Those are looping effects.

‘Bisexual’

Sexuality is one of the more compelling areas to apply talk of looping effects. Why? Lots of people – especially now – think they learn something about a person when they know the gender of the people they’re attracted to and/or have sex with. They think it’s an important part of a person’s identity. And in American society in 2020, it is. Americans organize interest groups, intentional communities, political groups, et al. around it.

They do so in part because US society oppresses and marginalizes people for nothing more than who they want to bonk. But whatever the reason, classification of sexuality changes how people think about themselves and approach the world.

I think this is profoundly strange, and I’m surprised more people don’t agree with me. There are lots of things about me, for example, that don’t seem important. I’m left-handed. My eyes are a mix of green, brown, and blue. I watch baseball, and I love the Yankees. Aside from a few Red Sox fans, those things aren’t too important to people. They’re not central to my identity in the way people think sexuality is.

Eye Color and Left-Handedness

But, you know, funny that. In certain times and places, many of those things were important. Racist societies like Nazi Germany worried about eye color. But I’d rather talk about the mundane. How about left-handedness?

Left-handedness was an issue in the US for decades. We have sayings in the English language suggesting left-handed people have suspect motives. They’re sinister, the word itself derived from the Latin word for left-handed. For generations, US teachers forced left-handed children to write with their right hand. And this is recent stuff! A teacher did it to me when I was a child. Most Americans recognized this as offensive by the 1970s, but my school was about a decade behind the rest of the country.

Imagine being concerned because a child uses the wrong hand to complete a writing assignment! It’s fucking stupid, and almost everyone now recognizes it as such. With only rare exceptions, we no longer think there’s anything interesting about eye color or left-handedness. Left-handed people are neither more sinister nor smarter than right-handed people. It confers no special properties, and, in fact, all we have in common with one another is that we write with our left hand. Sure, it ain’t all peaches and cream. Some of us have trouble getting hold of a left-handed baseball mitt or other products. But these things are now minor inconveniences, not social stigma or oppression.

Why shouldn’t sexuality be like that?

Identity Politics

It’s tempting to say we ought to approach sexuality the same way: we like who we like, and that’s that. To be a person who has sex with a certain type of person is to be nothing more than that. A cigar is just a cigar.

There’s a certain kind of identity politics in the US that wants to do this, to transform the world so that people treat oppressed sexualities more like eye color or handedness. In its most conservative form, its practitioners treat the world as though it’s already like this or about to become like this. Pete Buttigieg, for example, shuns the gay bar or tries to change the minds of bigots at Chik-fil-A or Salvation Army. He does so by showing the banality of his sexuality, its harmlessness to US social norms.

Others call this a politics of assimilation. They think queerness carries revolutionary potential. At its best, ‘revolutionary queerness’ is about new forms of community and social organization. And at its silliest, it’s about selfies and ‘queering’ various ordinary activities that aren’t in any sense queer – no matter how much a person wants them to be.

For my part, I encourage people to draw revolutionary potential wherever they find it. I don’t draw much from my sexuality. Because of my own history, rejecting religion opened more doors for me than rejecting heterosexuality. But your story might be different. That’s fine.

Bisexuality

Our words for sexuality and sexual orientation are relatively new. And it’s not entirely a process of linear discovery. For one, there was a time – and it wasn’t much more than a century ago – when people didn’t have any of these terms. At least not in the way we have them now, as terms allegedly describing some deep-seated part of a person’s identity.

The term ‘bisexual’ came from a long a history, one where sexologists first decided to classify sexual orientation at all and only then found those classifications lacking. Sexologists began from a homosexual/heterosexual binary, and it didn’t take long to reject the binary. Scientifically, anyway, even if not socially. Many people didn’t fit into either camp, and the field operated using dubious deviance models.

But ‘bisexual’ was always an unstable category. Even today, it’s easily misunderstood. Early concepts of bisexuality supposed bisexual people are equally attracted to men and women. Not only is this often not true, but it neglects the status of non-binary people and others who transgress gender boundaries. And so, people developed new labels like ‘pansexual‘ or reclaimed old ones like ‘queer,’ labels overlapping ‘bisexual’ to some degree.

In extreme cases, scientists engage in what’s called ‘bisexual erasure.’ For example, research teams who begin from an equal attraction framework tend to produce studies showing bisexual people, particularly bisexual men, don’t exist. That’s a problem.

Sexuality Spectrum

What did sexologists make of this? They stopped thinking about sexuality as a series of boxes and started thinking about it as a spectrum. The Kinsey scale is the most famous version of this. It even inspired a film. While I have a soft spot for Kinsey, especially since I attended Indiana University, the Klein grid is a more influential model. Unlike Kinsey, Klein accounted for both behavioral and emotional aspects of sexuality. He also accounted for individual changes in sexuality over time.

Even Klein’s work wasn’t perfect. His model doesn’t capture features of sexuality like the age of one’s partner(s), varying interest in different gender combinations, et al. No model is perfect, but some are better than others. I’d recommend Edward Stein’s book The Mismeasure of Desire to anyone interested in sexology.

It’s complicated stuff, and it’s constantly in motion. All include cases of looping effects at play.

But Is Bisexuality Real?

Here’s one story. People always had a sexual orientation. They had one thousands of years ago, and they have one today. It just took us – and it took scientists – a long time to realize it and come up with labels for it. Sexologists caught on, and now they’re constantly refining and improving their models.

And here’s another story. Sexuality isn’t all that important, at least not in any inherent sense. We like who we like, and we bonk who we bonk. No one thought it was central to our identities until the Victorians got huffy about deviant sexuality a bit over a century ago.

Which story’s the right one?

It’s complicated. Spectrum approaches really are better than binary models. And terms like ‘bisexual,’ ‘pansexual,’ et al. capture something important about about people. But how we think about sexuality, how we label it, how others treat us based on those labels? These things change us. And they don’t merely change how we think about our sexuality. They change our sexuality itself.

My sexuality – and your sexuality – is a lot different in 2020 than it would’ve been had we been born in, say, 1950 or 1750. Or, probably, in 2050.

And so, yes, bisexuality is real. But it’s real in a very contingent, very historical way. It’s real in certain times and places and against certain social backgrounds. It’s not real in a way transcending these guiding structures.

Return to Identity Politics and Looping Effects

I wrote about a different kind of identity politics in a previous post. Those politics are about addressing the issues of members of specific groups as a part of a deeper, transformative leftist project. People practicing those identify politics, when doing it well, recognize that identities are real in no more, and no less, the sense in which bisexuality is real.

NASCAR Dads and Bisexuals

As Hacking argued, looping effects complicate the social scientist’s world. Take the political scientist studying the politics of race. Race isn’t some stable feature of the natural world that she can study independently from human systems and attitudes. Whiteness changes, and who we include as white changes. Good social scientists recognize this and adjust accordingly.

In the end, ‘NASCAR Dad’ was a throwaway term – a term some pundits generated so they’d have a hot take to send to a magazine to meet a deadline. The philosophical story I’d tell about ‘NASCAR Dad’ bears similarities to the one I’d tell about ‘bisexual,’ but that doesn’t make the phenomena equally real or important.

Good social scientists separate what’s insightful from what isn’t.