I took a look at this month’s reading list and saw right away that it’s all about politics. I guess that’s not such a surprise for a political blog! But it’s actually not the case in most months. So, this month hits at the core issues we discuss here at the blog.

Read on, enjoy, and let me know what you’ve been reading lately!

Beverly Gage – G-Man

With this book, Gage delivers the first full biography of J. Edgar Hoover in decades, and I learned quite a bit from it! We get the history of the FBI and Hoover’s shaping of it. And she also focuses on Hoover’s sexuality in a careful way. In all, Gage’s book goes a long way toward explaining how Hoover built and kept power for more than half a century.

On that note, Hoover’s time in office spanned 8 U.S. presidents and many eras, all the way from the Progressive Era to Vietnam. Hoover skillfully used the politics of the day, even pulling off his greatest expansions of power under FDR during the New Deal and World War II eras.

That last fact says a great deal about the weaknesses of social democracy as a political demand. The left must remain vigilant about civil rights and liberties – and, above all, hold to internationalism – no matter who holds power.

How did Hoover approach his office? He used the full range of mainstream U.S. politics – from progressivism to the far right – to fight against communism. He built COINTELPRO, violated privacy rights, and undermined the left. This teaches us a lot about why we need an open, non-authoritarian, big tent socialist movement. One that builds links across borders of gender, race, and nationality.

China Miéville – A Spectre, Haunting

Miéville, well known as a writer of speculative fiction, writes a series of essays walking the reader through Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto. It’s short, well organized, and accessible – giving the reader context and an outline of the text. He also includes lots of original source material.

Miéville does the left a valuable service in his review of the nature of a manifesto as a text. He points out how it functions both to make claims and to urge the reader to do things. Miéville strikes a useful balance between criticizing the text where it’s wrong, and also clarifying that Marx and Engels were trying to bring about the world they predict.

I don’t always agree with Miéville’s reading of Marx and Engels. For example, I think he puts too much emphasis on the ethical theorizing he finds in the text. Much in spirit with Miéville’s approach, I’d say Marx and Engels make ethical claims only for the sorts of rhetorical reasons found in a manifesto, e.g., attracting a target audience on the basis of common moral intuitions. This is also quite in line with Marx’s earlier work in the 1840s. But that hardly matter. The point is that Miéville writes an accessible and relevant intro to a difficult text. He approaches debates with a sense of open mindedness and willingness to consider new perspectives.

That’s how any leftist should approach the Manifesto and its history.

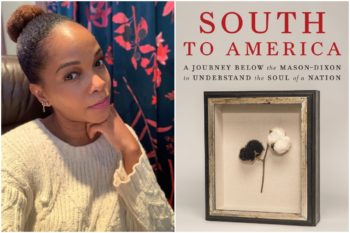

Imani Perry – South to America

Imani Perry goes on a tour of the South in order to look at her own family and reveal how the U.S. South represents the country as a whole. She wears many hats – historian, journalist, memoirist, and stream of consciousness author.

On the whole, it works. Perry pulls it together well, even if I found it pretty uneven at times.

Perry reveals a lot about the South. She especially brings out its border regions many wouldn’t consider southern. She travels to Annapolis, MD, West Virginia, and Washington D.C. And she writes a brief, but very familiar (I grew up in the area) chapter about Louisville. All these places have southern histories, even if they also find a home in another region.

As Perry moves through more typically southern areas, her thoughts drift, come together, and pry apart. She interprets interactions with people around her, often to the point of over interpretation. But she hits at striking insights, such as the links she draws between Beale Street and the history of American music. As well as her discussion of race and #MeToo.

When she misses – and she does miss a few times, such as during her discussions of white privilege and the wages of whiteness – I think she also does that in interesting ways.

David Roediger – Class, Race, and Marxism

Roediger tries in this book to synthesize Marxist approaches with approaches grounded in race. He touches on the term ‘white privilege,’ the priority of race or capitalism, and class reductionism, among other topics.

I think he succeeds and fails. He takes fellow leftists like David Harvey to task for failing to recognize that racial justice struggles target capitalism. And he discusses white privilege in an informed and useful way. I think all this goes well enough, and it’s key.

But he gets it wrong at various points, too. He also takes Harvey to task for drawing a distinction between capitalism and the logic of capital. According to Harvey, capitalism operates through identity categories like race, whereas the underlying logic of capital is independent from identity. Roediger disagrees, arguing that even the logic of capital itself is linked with race.

In short, Harvey is right about that debate. Capitalism uses race a lot, but it’s a contingent tool of capital. In a scenario where capital no longer finds race useful, it will use other tools. In missing this insight, Roediger says lots of strange things about leftist theorists from Cedric Johnson to Adolph Reed Jr. and others.

Finally, for better or worse, the book reads like straight intellectual history or even biography. This can be valuable at times. But at other times, the focus on minutiae distracts the reader.