In my very first post on this blog, I laid out for readers the Marxist term ‘base and superstructure.’ Lots of people new to leftist ideas could use a 101-level story about many of Marx’s key terms. And that especially goes for any term related to the analysis of economic relations over the course of history. In this post, I’ll approach the term ‘modes of production’ from a similar mindset.

Indeed, Marx didn’t just analyze capitalism and its social relations. He didn’t only talk about the transition from capitalism to a socialist society. He embedded all this within his broader theories of history. ‘Modes of production’ is a key term within Marx’s historical materialism.

Modes of Production

I think ‘modes of production’ is an intuitive enough notion. For Marx, a society’s mode of production is its current state of economic relations. Any given society has a set of property relations, social and legal relations of economic production, class relations, and all the powers and tools needed to do work. When you combine all these things, you get its current mode of production.

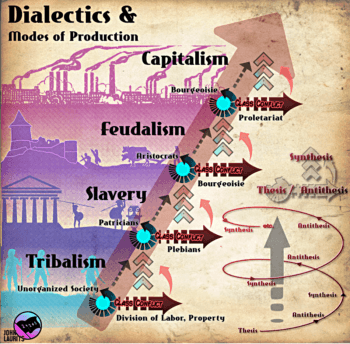

Marx thought history moved through stages. Each stage has its own mode of production. One mode of production forms, and then its own internal tensions produce crises. The next mode of production forms, ‘resolving’ the crises. But new internal tensions arise and produce new crises. And so on.

One mode follows another in a pattern. Marx believed society began from the ‘tribal mode of production’ – or primitive communism – and then proceeds through slave societies to feudalism to capitalism and finally to socialism. Marx also posited one highly intermediary stage. He called it the ‘Asiatic mode of production‘ and thought it sometimes appeared between tribal society and slave society. That spawned its own debates within Marxism.

But How Seriously Should We Take All This?

One big problem in modern leftism – especially within sectarian orgs – is the tendency to treat Marx as more of a prophet than a scholar. People try to figure out the line Marx laid down, and then they enforce it as Iron Law. This often leads to the enforcement of highly questionable interpretations of Marx, as with, e.g., Lenin.

We see a version of this with modes of production. But most of all, it’s not clear how deterministically Marx thought about the stages. Did Marx think every society must proceed through all stages? Must a feudal society first go through capitalism before becoming socialist? If so, should a socialist party in a feudalist society support the capitalist revolution and only afterward promote socialism?

As readers might imagine, those last couple of questions aren’t just hypothetical. 20th century Marxists – especially in Russia – spilled many gallons of ink fighting about these questions. But I should note that dogmatic adherence to strict historical determinism led to lots and lots of problems.

Seriously, But Not Too Seriously

Here’s where I come down on all this: I think Marx probably didn’t hold as strict a version of historical determinism as many people read him. But for me – and hopefully also for readers – the question of what Marx thought in the 19th century is far less important than the question of what we should think today.

I think the concept ‘modes of production’ provides us with a useful frame for thinking about history. Sometimes a very useful one. But it runs into limits. Marx clearly based it on European history. It applies less well to Asian history, and far less well to history among Native Americans. Marx did propose the ‘Asiatic mode of production’ as a solution to some of these issues. But that’s an ad hoc solution at best.

And so, while these stages are perhaps good rules of thumb, especially in Europe, they’re nowhere near universal. Things can go differently. As with most things Marx, these ideas are useful. But they’re not to be followed dogmatically.