It’s a bit trendy these days for leftists to dismiss talk of ‘human rights’ – or the ‘rights of man,’ as people once knew them. In truth, Marxists went even further. But it’s surging again in the last few years. In the older days, leftists dismissed all this as talk of ‘bourgeois rights’ or ‘freedom.’ Now they frame it more in terms of privilege or the ‘rights of man’ being only for white…well, men.

Where did all this come from? I’ll give an overview of Marx’s critique of human rights and the rights of man. This stuff comes from his early political philosophy. And I haven’t written a lot about that. I’ve focused in this blog mostly on Marx’s later work.

The Rights of Man in ‘On the Jewish Question’

On the surface, ‘On the Jewish Question‘ seems like a dull 1843 essay in debates among Hegelians about Jewish political struggles in Prussia. I suppose it’s that. Marx was born to a German family that had converted from Judaism to Christianity. It doesn’t seem like the essay would have much to say about the ‘rights of man.’

Yet it has a great deal to say. Despite embedding it in a much less interesting debate, I find what Marx says here far more accessible than most of his other work on the topic. I used to assign it to my political philosophy students. Marx’s overall point in the essay is that Judaism relates to society – at a basic level – in much the same way Christianity does. Both religions seek emancipation from the state in order to operate freely. The main difference, of course, was that there were far more Christians than Jews, allowing Christians to co-opt the state and persecute religious minorities.

As an aside, I’ll remind readers Marx was writing about 90 years before Hitler’s rise to power. What seems rather obvious now maybe didn’t in 1843. But enough about this. Let’s move on to what we should take from the essay.

Political Emancipation vs. Human Emancipation

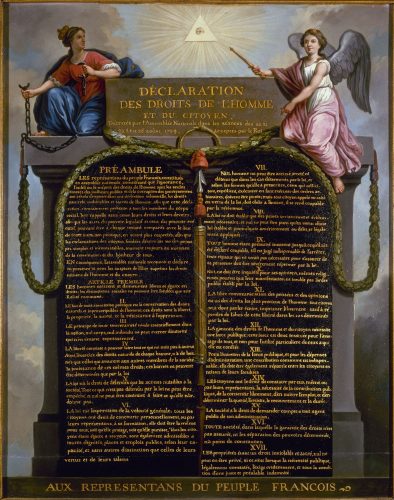

In making his point, Marx distinguishes between political emancipation and human emancipation. Political emancipation amounts to freeing the state from various institutions and social roles seeking to dominate it. And liberal political philosophers of Marx’s time advocated this: from the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of the French Revolution to Thomas Paine’s ‘Rights of Man’ to a Rousseau or a Mill.

Once emancipated, the state abolishes official state religions, property requirements for office, and so on. But this does not move beyond freeing the state. It doesn’t free people from those institutions and roles. The church or social norms can still dominate you. They just can’t use the state to do it. Religion, private property, gender, race, et al. still exist and still do their thing. And not only do they exist, but they often flourish.

Human emancipation, on the other hand, requires taking the next step and freeing people from religion, social systems, social roles, and other ‘private’ forms of domination.

Marx on the Rights of Man

Marx quoted extensively from the French Revolution material. He also quoted relevant passages from the constitutions of individual U.S. states. He drew from these a working list of the rights of man. The list includes things like: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, et al. But, most importantly, Marx concluded these political rights are, in fact, a kind of illusion.

What’s the illusion? In short, these rights create for people the appearance of citizenship or political participation. However, in fact, they’re grounded in a kind of individualism premised on lack of political participation. They don’t facilitate political and social participation for most people.

These rights reduce to a few basic principles: liberty, equality, security, and property. These things require equal treatment under the law and freedom to do things without state interference. But they’re not genuine liberation. Why?

To participate, people must access the means of participation. What good is freedom of speech to the person without an education or access to media outlets? What good is freedom of religion to the person who lives in a civil society that pushes religious dogma and blocks all attempts to question that dogma? And what good is the freedom to purchase a house if police repress the neighborhood or if the banks refuse to give loans?

Genuine Liberation

Genuine liberation goes beyond all this. It can’t reduce to freedom from the state. It can’t retreat to private wills separate from the community. Marx then goes on to specify genuine liberation. But this is Marx at his chewiest. Here’s the quote:

Only when the actual individual man absorbs the abstract citizen of the state into himself and has become in his empirical life, in his individual labor, in his individual relationships a species-being; only when he has recognized and organized his ‘own forces’ as social forces and therefore no longer separates the social force from himself in the form of political force; only then is human emancipation completed.

I can leave this as an exercise for the reader, but a few notes. First, there’s a lot of background literature on what Marx had in mind by ‘species-being’. At a minimum, he means it as a kind of harmony between individual people and social relations. Second, genuine liberation includes both freedom from religion, social roles, et al. and a positive sense of community. And third, some version of the ‘rights of man’ will likely still exist in the liberated society. But they amount to a ‘positive liberty’ rather than a ‘negative liberty.’

Postscript: Freedom of Speech, the Press, et al.

Does any of this mean we – as leftists – should actively oppose or subvert ‘human rights,’ the ‘rights of man,’ freedom of speech et al.?

Well, no. I’ll write more about this next. But I strongly suspect Marx wouldn’t endorse any attempt on the left to actively erode these things. Not because Marx loves these things. He doesn’t. It’s really more a pragmatic question of leftist politics. Eroding rights that free people from the state creates easier paths for state intervention.

As leftists, we don’t really think that will work out well for us, do we? I mean, when has it ever?