While I’m not sure I can compete with the sci-fi and radical politics of last month’s reading list, I do have some interesting things on tap for this month! After reading the quadruple bio of classic sci-fi authors, I decided to return to Heinlein.

Read on to see what I’ve mixed in with classic Heinlein.

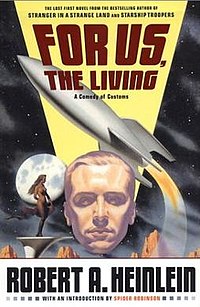

Robert Heinlein – For Us, The Living

We’ll get to that in a minute. But Heinlein first. He never actually got around to publishing his first novel, written back in the late 1930s. He mined it for stories, especially in his Future History series. But he never published it. His estate published it.

How did it go?

It’s a fine enough story, but I think there’s probably more scholarly interest here than sci-fi reader interest. Heinlein begins from a solid premise, focusing on what would happen if a person from 1939 moved 150 years into the future. It offers Heinlein a platform for making predictions about the future before the outbreak of World War II. And it offers him a rare early opportunity to imagine a world that has implemented his own (early years) politics.

That said, it’s clearly the work of someone not yet in his prime as an author. It’s preachy. Most of the second half is dominated by a mouthpiece character lecturing the reader on Heinlein’s economic views.

In the end, I think the first half has a strong enough plot to make the second half worth slogging through. But I’m also a Heinlein fan.

Rosamond McKitterick (ed.) – The New Cambridge Medieval History II, 700-900

Readers might know I’ve been reading Roman history – up to and including the Fall of the Empire – for some time now. But I decided to continue reading into medieval Europe. So, here I find myself looking at the second volume of the New Cambridge Medieval History.

It’s quite comprehensive. In this essay collection, historians write about political history in the 8th and 9th centuries, but also their art and literature, book culture, and political and economic relations. And it includes all of Europe. Not just the Franks and Charlemagne’s empire. It also touches on British and Irish history, northern Europe, Byzantine Italy and Constantinople, and the Visigothic and Arab areas of Spain.

The essays can come off as a bit dry, but I learned a great deal. The book also complicates traditional narratives of the period as a ‘Dark Age’ or an era with little social mobility. In fact, there was more mobility and communication than once thought.

Jeffrey Pfeffer – Leadership BS

The leadership industry doesn’t impress Pfeffer – not its pile of books, nor its seminars, conferences, TEDx Talks, consulting, and academic programs. He argues against the industry’s inspiration and moral uplift and in favor of social scientific literature that shows, in his view, better insight into actual leader behavior.

In short, Pfeffer argues that the leadership industry tells leaders to be honest, authentic, builders of truth and good relationships, and so on. But he shows that actual leaders do the opposite. And he tries to draw lessons from that.

However, he waffles on exactly why actual leaders do the opposite. At times, he suggests that dishonesty, inauthenticity, et al. serve to make a company more successful. But at other times, he claims it’s what makes leaders successful, but not their companies, and that the success of a leader a their company tends to diverge.

That latter possibility is one we should find more interesting. It shows rather well some of the systemic problems with capitalism. And while Pfeffer offers a variety of ‘fixes’ to align the interests of companies to their leaders, he fails to get at the underlying problem. He gives a brief nod near the end of the book to employee ownership, but he leaves that space mostly unexplored.

Shelton Stromquist – Claiming the City

Stromquist issues here what he calls a global history of socialism. But unlike most such histories, he focuses on the municipal level. And he strives to make that history both global and comprehensive. He largely succeeds at the latter, though less so at the former.

Indeed, he tells a sweeping history that moves all the way from city formation – battles between the rising bourgeoisie and aristocratic and royal elements – to dissent and party splitting during World War I. He usefully situates much of the history of municipal politics in battles with class undertones. For example, in the U.S. and Europe we see constant battles between municipal home rule and states that re-centralize authority. These battles ebb and flow as working-class people take and lose local (and national) authority. We see these battles continuing all the way to today.

Stromquist usefully compares and contrasts movements in the U.K. to those in Germany, the U.S., Sweden, and Australia and New Zealand. The U.K. municipal socialist movement, for instance, was far less centralized than the German model. But whereas the German movement got closer to national power, the U.K. movement accomplished more. The German socialist movement looked, to me, like a much stronger version of the 2020s DSA, even suffering from many of the same problems (e.g., growing too quickly and unsustainably through relying on a national political narrative). He even tells a story about German municipal socialists under the Erfurt Program who fall into the kinds of technocratic traps that U.S. progressives fall into, running a state for workers without involving them in it.

Finally, Stromquist complicates lots of standard narratives about city politics versus national politics. City politics weren’t always small and insular. Some even better implemented socialist internationalism than their national counterparts. They weren’t all ‘sewer socialists.’