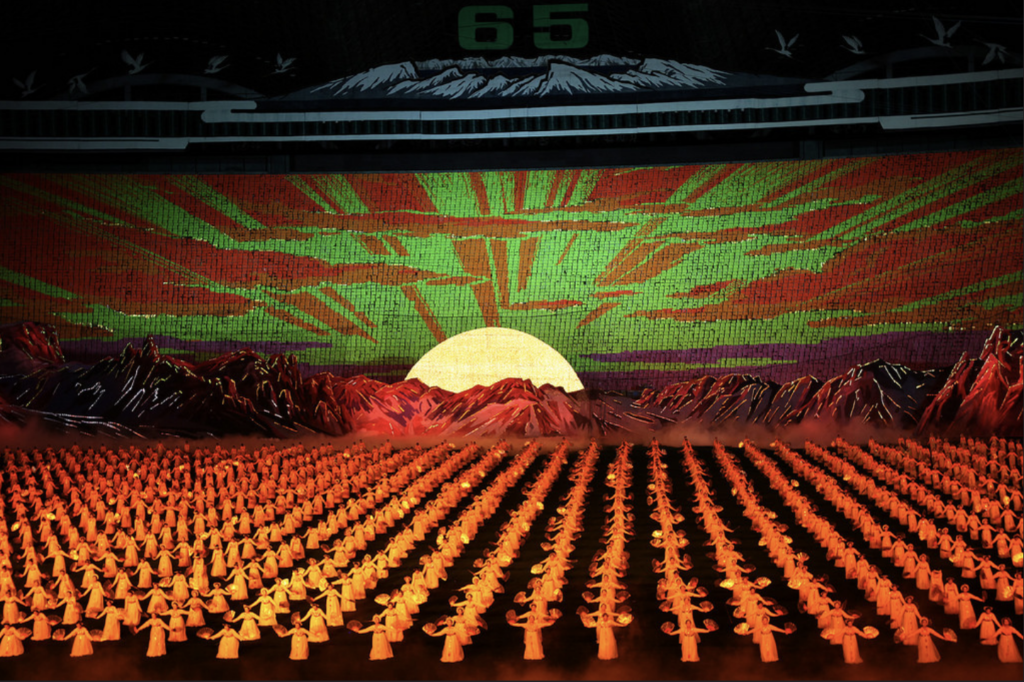

Source: Roman Harak (https://www.flickr.com/photos/roman-harak/5015832858)

We know Trump eats up most of the news cycle these days. Not much foreign policy gets through unless it’s about Russia. But there have been a lot of developments in relations between the US and Asian countries, particularly North Korea.

It’s all over the map. No pun intended.

I also think much of the US left still needs basic orientation around foreign policy issues. A few well known analysts (e.g., Noam Chomsky) talk a good game, but even Noam focuses on details that might not be helpful for beginners.

I’m writing about North Korea in this post. But at a broader level, I’m going to write a series of 101 level posts on foreign policy in the coming months. I’ll write in a way that doesn’t require the reader to have much prior background.

In these posts, I won’t hash out every minor detail. Nor will I solve every problem. It’s more about getting down the basics about what’s happening and how to reason through issues regarding the US’s relationship with the world.

My leading questions are: what are these conflicts really about? What are the underlying issues and interests at stake?

Standard Narrative About North Korea

There’s something close enough to a standard American foreign policy narrative about North Korea. It goes like this:

North Korea is an authoritarian hermit kingdom, and it’s led by an unstable dictator. Kim Jong-un is trying to get nuclear weapons, and he’s doing so in order to gain the resources his country’s failed economy can’t produce itself. He’s holding his own citizens hostage until the world makes ransom payment, and he’s not afraid to use nukes.

The United States, on the other hand, is in a bind. It has the best intentions at heart, but it’s balancing these good intentions with its national security interests. The US imposes sanctions against North Korea to empower its people to replace Jong-un with democratic leadership. And the US provides aid and eases sanctions whenever Jong-un lessens his aggression.

When you listen to American politicians and news coverage, you’ll hear some variation on all that. Even when it doesn’t come out directly, it’ll be the unstated assumption behind the talk.

The Problems with the Standard Narrative

The standard narrative isn’t 100% wrong, but it’s close. Kim Jong-un is an authoritarian leader, and it’d be better if countries didn’t have those. But that’s about where the standard narrative stops being correct.

North Korea isn’t an irrational actor or the primary aggressor. It behave as a rational actor operating through a generally realist foreign policy lens, as many nations do. Realist theories of international relations have their problems. But realism is the framework that most countries accept on the surface. What this means is that North Korea sees the world as a set of conflicts between competing powers. It knows that the US has interests in East Asia in conflict with its own. And it knows that the US is the far more powerful of the two countries.

And so it pursues nuclear weapons as a deterrent.

But it’s not just that it pursues nuclear weapons as a deterrent. It fears an actual US invasion, and it’s not wrong to fear one. The US has already invaded the country once. And the US repeatedly invades or destabilizes countries when it’s in its perceived national interest to do so.

To be clear, it’s not just that North Korea is a rational actor and the US thinks it’s irrational. Not all American politicians accept the very strong version of the standard narrative I wrote above. Some liberals reject it in part. One could argue that the Bill Clinton Administration rejected some of it. But even the most liberal of US politicians still accepts the basic premise that North Korea is the primary aggressor.

But that’s false, too. Any careful look at the timeline here shows that the US is the primary aggressor, especially after the 1995 Republican Congressional victory. And especially after George W. Bush’s declaration of an ‘Axis of Evil’ in the 2002 State of the Union address. North Korea only fully committed to a nuclear program after that.

Let’s also be clear that North Korea knows perfectly well what happened to the last country that backed off its deterrent against US imperialism.

Trump’s Entry

And so, we have at least the bare outline of a leftist narrative.

But things get complicated at this point. Despite nitpicky objections, there’s at least a broad bipartisan consensus on foreign policy in the US. We know that Republicans disrupted this a bit by voting against everything Obama proposed. But there’s still far more consensus in foreign policy than anywhere else in US politics. And you still have to get pretty far into the details before revealing any disagreements.

Often this is a bad thing. Consensus in foreign policy often means everyone in Congress and the White House coming together to do the wrong thing.

This brings us to Trump, then, doesn’t it?

Trump campaigned against war. Sort of. He tapped into a kind of nativist, isolationist strain of thought that’s been around in America for a long time. Whether he sincerely holds these views is a bit up in the air, but he certainly criticizes US wars and warmongering politicians. These ideas are popular among his base.

Democratic Response to Trump

Democrats, on the other hand, respond to Trump by fully endorsing the US foreign policy consensus. Rachel Maddow, for example, responded to Trump’s ending of US military exercises in South Korea by stupidly advocating for more US military in Korea and going on about Russia in a total non-sequitur.

I’ve chosen Maddow because she competently presents the standard line. Maddow here is representative of Democratic Party thought and presents one of the better versions of the failed standard foreign policy narrative. She also explains, correctly, that the ultimate goal of US foreign policy in the region is as much about containing China as it is changing the North Korean regime.

Barack Obama’s policy followed the failed standard narrative. Had Hillary Clinton won, she’d have been a highly competent enactor of the failed standard narrative.

Maddow’s argument, and the Democratic Party argument, is that Trump shouldn’t have canceled the military exercises without North Korea, the aggressor, first providing a concession on nuclear weapons. This makes sense only on the assumption that North Korea pursues nuclear weapons offensively, not defensively.

The assumption, though, is false. And it takes down with it the entire Maddow and Democratic Party argument.

Trumpist North Korea Policy

As with most things Trump-related, North Korea policy has zigzagged everywhere. Trump carried out an extensive Twitter feud with Kim Jong-un in 2016 and 2017. In perhaps typical fashion, he negotiated by bringing the US and North Korea uncomfortably close to nuclear war.

There’s not a lot more to say about that.

Meanwhile, Trump repeatedly threatened South Korean president Moon Jae-in. Trump’s main goal was to coerce South Korea into revising its existing military agreement with the US.

The agreement establishes a US imperial presence in South Korea, allows the US to use South Korea as a weapons base, and allows the US to intimidate other regional powers (hint: China). South Korea pays a portion of the costs. Trump’s beef with the agreement is that he thinks South Korea doesn’t pay enough.

With the agreement under threat, South Korea moved to establish closer relations with North Korea. Hence, they’ve come closer to peace than at any other point in the last 50 years. The US, trailing behind, signed a lesser agreement with North Korea that’s playing second fiddle to the one between North Korea and the South.

Trump and the Foreign Policy Consensus

With the exception of his signing of a separate trade deal with South Korea, mainstream US foreign policy experts think Trump is an idiot on North Korea and Korean policy. But that’s not because of Trump’s risking of nuclear war. It’s due to the other stuff. Mainstream US foreign policy experts aren’t too keen on peace between the Koreas. They’re much more interested in preserving US dominance of the region and blocking China.

Trump’s policy ideas in North Korea aren’t helpful to that. They’re something of a failed attempt to carve out a new kind of foreign policy regime. Thus, Trump’s foolishness arguably accomplished some things. Accidentally. Trump has no idea what he’s doing there.

Conclusion: A Leftist Narrative on North Korea

And so, here we are. Here’s my attempt at a basic leftist narrative that provides, I take it, a 101 level understanding of the conflict:

The current conflict stems from the Korean War and its aftermath, which was caused primarily by US aggression. The US is currently an imperialist, occupying power in South Korea and is the primary impediment to peace. Its apparent intentions are national interest: it wants to maintain domination of East Asia and limit Chinese power and reach. Trump’s rather incompetent bungling of the situation has, ironically, pushed the North and South Koreans closer to peace. On balance, the conflict is probably better in early 2019 under Trump than it would’ve been under Clinton.

This is a sad reflection of how off-base Democrats are on foreign policy issues. And it’s a warning for 2020: the Democrats may try to nominate someone to Trump’s right on foreign policy issues.