We see lots and lots of coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Much of it’s clickbait. Some of it can inform us, sometimes in great depth. We can find, for example, many in-depth accounts of what hospitalization or ‘long COVID‘ is like. But very little of it – almost none – gives us much in the way of practical, useful information for risk assessment.

In particular, the news coverage doesn’t give us a good sense of the proportional danger to specific groups of people. This goes even more so for the delta variant, where the vast majority of the coverage presents misleading information. In that last sentence, I linked to the CDC’s overview, which is much more informative than the news coverage. With delta, the news veers between COVID denialism and gross exaggeration of the risk to specific groups, children prominent among them.

So, I’m going to take a crack at risk assessment here. I’ll present CDC data and draw tentative inferences about risk by age and vaccination status. Let’s see if I can provide some of the missing risk assessment info.

Data on Death by Age and Vaccination Status

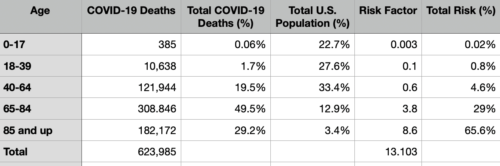

The CDC presents all sorts of useful data on death from COVID-19 in the U.S. I’m going to focus here primarily on age. If you look at the table below, I’ve taken all these data from the CDC page I linked in the previous sentence. I reworked the data to clearly show three things: the number of COVID-19 deaths in each age group, the percentage of total COVID-19 deaths from each age group, and the percentage of the U.S. population that comes from each age group.

One quick note: those latter numbers I gathered from census data, not from the CDC.

In addition, I created the final columns, ‘Risk Factor’ and ‘Total Risk.’ There’s nothing especially scientific or technical about those terms. I merely divided percentage of deaths by percentage of population to come up with a single number that gives a flat comparison of risk by age, adjusted for population proportion. My idea here is to come up with a single basis for comparison that more clearly shows the different risks to different age groups. I think those terms do the job nicely. Any number higher than 1 represents elevated risk relative to the population as a whole.

These data are all up to date as of August 26, 2021.

In short, age matters. A lot. A person who’s 85 years old or older, over the course of the entire pandemic, has faced a risk of death roughly a few thousand times greater than someone under 18. This is pretty relevant for risk assessment, to say the least.

Did the Vaccines and Delta Variant Change Things?

We know that in recent months, the vaccines made a big difference in the U.S. They suppressed the alpha variant, and they made a big dent in the spread of the delta variant. But, we also know that children under 12 remain ineligible for vaccination. Did that change the risk assessment?

The short answer: yes, it did. It surely reduced the gap between older and younger Americans in terms of risk. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines remain about 90% or so effective against hospitalization and death. Unvaccinated people are about 25+ times (in some local studies, even 100+ times) more likely to face hospitalization and death than vaccinated people. And people over 65 are the most vaccinated group in the U.S. These things all reduce the gap.

But, from the above data, it should also be clear that a big gap remains, even after vaccines and delta. The gap in risk between children and the elderly was so enormous last year that it remains, even after administration of a highly effective vaccine. And so, older Americans – even vaccinated older Americans – still face greater risk than children under 12.

People correctly infer that young people face greater risk, relative to where they were last year. But I think they might not quite have a sense for exactly where they were last year.

Vaccines and Death

In highly vaccinated countries like the UK, most people who die from COVID – even now – are (often vaccinated) older people. This doesn’t mean the vaccines failed. It just means that they greatly reduce – but do not eliminate – the risk of death among a group that was at even greater risk before the vaccines. And in the U.S., more than four times as many vaccinated adults died in the last few months than unvaccinated children died in the last year and a half.

What does all this mean? Vaccines greatly reduce the risk of serious illness and death for older Americans, but they still face higher risks than younger people.

COVID Risk Assessment by Age and Vaccination Status: Some Inferences

Here’s my attempt to summarize what all this means for risk assessment by age and vaccination status. From the evidence above, here are the risks from greatest to least.

1. Unvaccinated adults (highest risk, by far)

2. Immunocompromised people (high risk)

3. Vaccinated adults over 65 (large drop in risk after the second group)

4. Vaccinated adults age 18-64

5. Unvaccinated children age 12-17 (large drop in risk after the fourth group)

6. Unvaccinated children age 0-11

7. Vaccinated children age 12-17 (very low risk, 0 confirmed deaths that I’m aware of)

A few ambiguities remain, especially as concerns the ordering of (1) and (2), as well as the ordering of (5) and (6). But I think this is the best conclusion we can draw.

Furthermore, this all shows proportion of risk. The absolute risk to any group may vary a lot, depending on the level of community spread. When community spread is low or non-existent, hardly anyone is at risk. And when it’s high, everyone faces some degree of risk, even unvaccinated children, though those risks remain much lower than the risks faced by older Americans or unvaccinated adults of any age.

Lessons Learned

I’d like to highlight a few lessons I’ve learned from this exercise.

First, while the press pointed to the greater risk faced by older Americans, they did a poor job giving us the proportions. Older people face risks hundreds of times, probably even thousands of times, greater.

Second, the way the press presents information leaves us with difficulties in our own risk assessment and our policy decisions. The U.S. should’ve acted much sooner and more effectively to protect older Americans, especially in nursing homes and in the workforce. And this remains true even during the vaccine and delta variant era. Furthermore, the lack of good information leads people to misstate the facts, which I’ll discuss in the next section below.

Third, we still haven’t come to grips with how populations interact and flow. Telling people to get a vaccine is important, but we still need to account for how older people interact with the community. If we’re planning events, school traffic, work traffic, and so on, we should do what we can to keep even vaccinated older Americans separate from children under 12, especially unmasked children under 12.

To apply this to my own family, I’m a 38 year old in ‘normal’ health. I still face risks. Those risks are greater than those my young cousins under 18 face. But I have other family members: an 88 year old vaccinated brother of my grandfather who’s currently in a Houston hospital with COVID and pneumonia, an unvaccinated aunt and uncle, a vaccinated uncle with COVID and COPD, a vaccinated parent with a history of COPD, and so on. They face greater risk than I do. We should aim policy first and foremost at protecting them.

An Example of Risk Assessment: Mask Mandates in Schools

The example of mask mandates offers a way to apply some of these lessons. It also lets us see the politicization of COVID-19. As the press did note, Trump supporters tend to underestimate risk while liberal Trump opponents tend to exaggerate risk. I find both halves a problem in their own way.

Mask mandate opponents tend to look only at the risks to groups (5) and (6) in isolation from the rest of society. They (mostly correctly) see those groups as low-risk, and then (falsely) conclude that we don’t need masks. The problem? Children don’t exist in isolation from the rest of society! Children need caretakers, like parents, grandparents, teachers, principals, and so on. People from groups (1)-(4), i.e., people who face greater risk from COVID-19.

Mask mandate supporters overestimate the risks to groups (5) and (6) in pursuit of the otherwise noble idea of mask mandates. Unvaccinated children do face risks. But those risks are still lower than almost anyone else. Even in absolute terms, the risks are perhaps a bit higher than an ordinary flu season and lower than the risks children face from pneumonia (see the CDC data link above for more on this). No one advocates mask mandates for these other things. So, were risk to children the main issue, we wouldn’t need mask mandates in schools. We need them primarily to protect the people around children.

And so, I support mask mandates for schools. They disrupt chains of COVID-19 transmission from children to unvaccinated adults and immunocompromised people, as well as to vaccinated older Americans. They help keep pediatric hospital admission numbers down. But mask mandates are an issue where it’s important not just to come to the right view, but to come to the right view for the right reasons. Otherwise, mask mandates are open to strong objections.

Postscript: Why Death?

I’m going to finish by addressing a common objection I hear, particularly from liberals who want to claim that children face greater risks than the evidence shows. They sometimes say that we should focus on hospitalization or long COVID rather than death. I disagree. Here’s why.

First, there’s the seriousness and finality of death. It’s the worst outcome. It’s the main thing we want to prevent from happening. That’s probably reason enough, but I’m going to set this one aside.

Second, the underlying claim doesn’t appear to be correct. As far as I can tell, the data on hospitalization also shows a strong imbalance in risk by age and vaccination status. And it shows these differences aren’t much less than those we find with death.

Third, the hospitalization data is less reliable than the data on death, at least for the purpose of risk assessment. Those data have a specific problem: some of the people hospitalized with COVID aren’t hospitalized because of COVID. This is especially an issue with children, where perhaps 35-40% of the children in the hospital who have COVID are in the hospital for unrelated reasons (and happen to test positive for COVID while in there). And so, hospitalization remains an important metric, but not so much for our purposes here.

Long COVID

And then there’s long COVID. It’s something that should concern us. But researchers still don’t know much about it, even down to what, precisely, it is. Current definitions vary. As people currently use the term, it can pick out everyone from people who had COVID and made a full recovery after a couple of months to people who still suffer from COVID-induced heart problems, breathing problems, diabetes, or dozens of other conditions more than a year later.

Eventually researchers will start putting this into shape. And when they’re done, ‘long COVID’ will probably become a much narrower and more specific term. It’s highly unlikely that people who fully recover in a couple of months have the same medical condition as people who suffer from issues a year later. At this point we simply don’t know how many people have a discernible condition that warrants the label ‘long COVID’ (or a successor label we don’t yet know about).

And so, I’d be extremely wary of any article that claims a certain percentage of people have long COVID. We have no idea what the real percentage might be. Long COVID is serious, but we don’t know how prevalent or how long it lasts.

However, with all this said, despite its finality and concreteness, death isn’t a perfect indicator. It can be a slippery medical term in its own right, and sometimes we don’t know the precise cause of death. But it forms a more solid basis for risk assessment than any alternative. By far.