Analytic and Continental philosophers aren’t friendly with one another.

With depressingly few exceptions, they ignore one another’s work. They create parallel conferences, journals, publishing houses, and even philosophy departments at colleges. While we can find examples of philosophers who engage meaningfully across traditions, even many of those philosophers engage mostly to heap scorn on the other side.

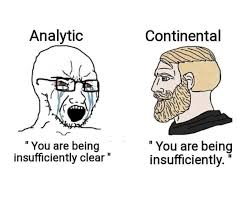

Anyone who made it through grad school in philosophy knows all the stereotypes. Analytics are pedantic, black and white thinking logic choppers. Continentals are pretentious charlatans more interested in literary theory than in getting at core philosophical notions like reality and truth.

Recently I read Lee Braver’s book A Thing of This World, which makes an attempt at a fruitful intervention into this state of affairs. Having read it, I regret to say the book sat on my shelf for more than a decade before I picked it up.

It’s a great read.

Grad School

Before I left academic philosophy, my own work stretched across the analytic-Continental divide. I worked in contemporary philosophy rather than the history of the field, but scholars working in my main areas of philosophy of the social sciences and feminist philosophy drew as freely on Continental figures like Heidegger and Foucault as they did on the philosophers from the analytic canon favored by the departments in which I was trained.

I benefited from great advisers at both the undergrad and grad level, with a grad adviser conversant in both traditions. But I still lacked a larger intellectual community in grad school, given the purely analytical nature of the department.

Braver provides in his book a framework for how to tie these areas together. His framework allows us to tell a story about how the two traditions engage with the same issues in parallel. In short, he uses an analytic typology of realism to trace the anti-realist views of Continental figures, beginning with Kant and moving through Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, and Derrida. These philosophers modify and transform the Kantian Revolution in philosophy in increasingly anti-realist ways.

Perhaps most interestingly of all, Braver connects all this to some of the challenges to realism found within analytic philosophy. Along the way, he relates Continental figures to everyone from Wittgenstein to Quine, Dummett, Austin, Davidson, and others.

Reading it Earlier?

As I read, I thought about how I might have applied the book to my own work. What might Derrida have to say about the more skeptical approach to social practices in the work of Stephen Turner? Could I have drawn more connections to the later work of Heidegger and Foucault? How might have I developed my own interest in historical change and social ontology?

Braver’s notion of a Kantian and a Heideggerian Paradigm in Continental philosophy could’ve proven useful. Framing this divide in terms of an active knower versus a historical subject provided me with an excellent way to think about the Continental canon. Perhaps I could’ve used it to better situate my work with respect to these figures.

Maybe I even could’ve used it to better understand the work of Wittgenstein and J.L. Austin in the analytic tradition.

It’s hard to say.

Final Thoughts

I’m not saying reading Braver’s book 15 years ago would’ve revolutionized my own philosophical approach.

I do think, though, that it could’ve expanded the range of conversations I had. It may have helped me understand and engage with more conference programs. It could’ve provided me with some of the skills needed to be a more helpful colleague and more competitive job market candidate at certain sorts of departments.

More than anything, the book stands out to me as useful for interpreting a difficult philosophical tradition. It also intervenes in the sociology of philosophy in a welcome and desperately needed way.

Here’s to hoping analytics and Continentals pick it up and talk with one another.