As leftists, we have a short term agenda: Medicare for All and other social democratic programs to meet basic needs, tenants unions to fight landlords, et al. But we don’t yet know how to get from there to full socialism – a democratic system of ownership and control over economic resources. While the topic has gotten long overdue attention on the left recently – see, for example Bhaskar Sunkara’s book The Socialist Manifesto – major issues remain. One of these issues is the ‘transition trough.’

Let’s talk about that.

What is the Transition Trough?

Suppose a strong working class party wins power in U.S. elections and turns the country toward social democracy. It wins several elections and establishes single-payer health insurance, a strong minimum wage, a large jobs program modeled on the Green New Deal featuring green jobs, a public housing program that ends homelessness in all but the most extreme cases, and so on.The works. Basically the Bernie Sanders platform.

This would make a huge difference in people’s lives, and it would go a long way toward sharing the benefits of American wealth with its people. But it wouldn’t establish socialism. To get to socialism, the working class party would need to push beyond social democracy into changing who owns and controls workplace production, tools, decisions, et al. How would it do this? Maybe it establishes and funds workers’ and consumers’ cooperatives. Maybe it directly seizes major industries and turns them over to their workers. The point is that these are the sorts of steps needed to move from social democracy to socialism.

What happens then? Marxist sociologist Erik Olin Wright thought it would trigger massive resistance from capital. And we’re talking the works here: capital flight, economic sabotage, political violence, et al. This, in turn, would result in sharply declining material conditions for ordinary people. Our standard of living would decline. We’d have increasing poverty, food and medical shortages, and lots of other problems. This phenomenon – the gap between our expectations and the early results of transitioning from social democracy to socialism – is what Olin Wright called the ‘transition trough.’

The Gap

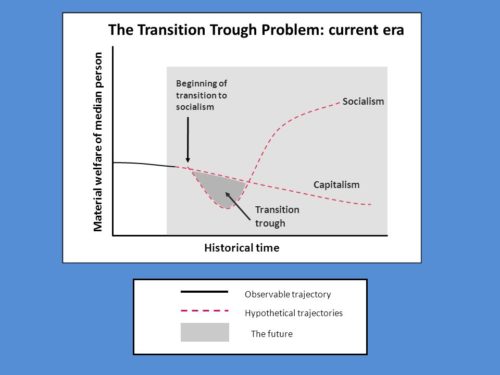

Here’s where the transition trough enters the picture. Take a look at this graph.

This shows the relationship between people’s expectations and the reality resulting from a socialist transition. At most times and places, people expect at least a modest rise in their standard of living. And while a socialist transition offers a steep rise in standard of living, it starts with a large drop. That drop creates a gap – the transition trough – that isn’t what people sign up for when they vote for socialist transformation.

What’s the Problem?

‘Of course capital will fight back!” some socialists reply. Couldn’t a socialist government educate people about the benefits of socialism once it’s fully implemented? Wouldn’t that allow the socialist government to ride it out?

Olin Wright argued ‘no,’ and that’s why it’s such a big problem. The kind of socialist society we want is one that’s democratic and egalitarian. And the only way we’ll get that kind of society is through democratic and egalitarian means, i.e., with mass organizing and winning elections. The alternatives are varieties of authoritarian socialism that consistently produce bad results.

It would take a long time, probably years, for a socialist government to move through the transition trough and establish a functioning socialist system. At the very least, Olin Wright argued, it’d take a few election cycles. This means the government would need to get re-elected. However, it’s unlikely a socialist government could hold together a winning electoral coalition through a major period of capital flight, political violence, and other forms of uncertainty and instability.

As a result of these factors – Olin Wright argued – the socialist government would lose and its replacement would re-establish capitalism.

Is Olin Wright Correct?

I think Olin Wright’s claims are plausible. Yes, capitalists will put up massive resistance to socialism. They even heavily resist much more modest reform programs, like the famous Meidner Plan in Sweden. And, yes, it’ll take time to work through the transition trough. How long? It’s hard to say. Surely at least a few years and likely longer. I’ll discuss below some ways of shortening it.

In sum, there’s plenty we could poke at, but I’ll give Olin Wright the benefit of the doubt thus far.

How Do We Solve the Transition Trough?

But this leaves us with the question of how to address the problem. In his book Envisioning Real Utopias, Olin Wright sketched out three options worth mentioning. We can: a.) speed up the socialist transformation and exit the transition trough more quickly; b.) wait for the economy to get so bad that people were expecting a decline in their standard of living anyway; or c.) convince people to value democratic and egalitarian socialism even at the expense of their own standard of living.

Olin Wright wasn’t impressed by these options. Nor am I. As for (c), it’s unrealistic, though Venezuela was perhaps a mild exception during the 2002-2003 crisis. Few people become that committed to ideology or morality. But it’s also an odd line of thought for a socialist in the sense that collective materials interests have always been a core part of socialist projects. It’s hard to set them aside. And (b) is not only depressing, but it also calls to mind the worst of accelerationist projects. A dire economy is as likely to produce authoritarianism as it is to produce socialism.

This leaves us with (a), which I find more promising than Olin Wright does. I’ll return to that thought later.

A Positive Class Compromise?

Some Marxists tell a simple story about the relationship between working class interests and capitalist interests. In this story, these interests are inversely proportional. As workers achieve material gains, capitalists lose. And as capitalists achieve their material gains, workers lose.

It’s a story of irreconcilable class conflict, and it’s one we can find in the text of Marx’s Capital. However, a careful reading of Marx acknowledges he intended Capital as a schematic reading of capitalism. It’s capitalism in theory, an idealized capitalism and its relations. In the real world, capitalism is much more complicated.

Consequently, we might imagine circumstances where social relations in actually existing capitalism are less confrontational. We might even imagine ones where positive class compromise – real compromise, not just worker capitulation or mutual resignation – is genuinely possible. And that’s where Olin Wright goes with it. He thinks we can’t solve the transition trough, and therefore can’t transition to full socialism. At least not in our current time. And so, he looks for the best and most sustainable form of social democracy we can get.

Social Democracy and Real Utopias

This takes us back to Olin Wright’s work in Envisioning Class Utopias and Understanding Class. He thinks we can ‘solve’ the transition trough through positive class compromise between the working class and capitalists. But how do we do that, if worker and capitalist stand in total conflict?

He thinks worker and capitalist interests aren’t always inversely proportional – that the relationship is more complicated – and we can fix social and legal structures in such a way that both worker and capitalist can be better off together.

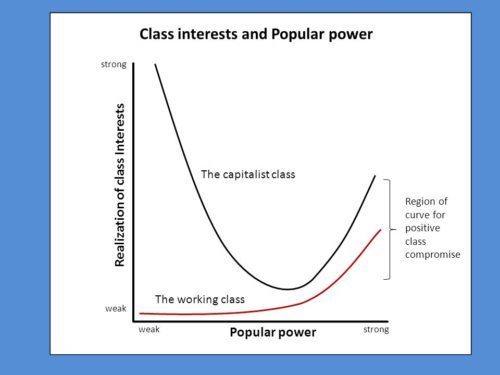

Hence, positive class compromise. Here’s a representation of how Olin Wright thinks all these things – worker interests, capitalist interests, and social and legal structures – most likely relate to one another.

This graphic shows how working class and capitalist interests change in relation to one another. When the working class is extremely weak, the result is a capitalist ‘utopia.’ And then capitalist interests decline as workers get more powerful, form unions, et al.

But, eventually, good unions and workers’ organizations serve to stabilize the economy, labor markets, et al. When companies take care of their workers, their workers stay on the job longer, become more productive, buy more consumer goods, et al. This is all pretty good for capitalists. Not as good as the capitalist utopia, but better than perpetual class conflict.

The positive class compromise Olin Wright seeks is one where we set up laws, institutions, et al., to make the capitalist utopia impossible to achieve. In such a situation, it’s in the best interest of both capitalists and workers to seek social democratic compromise.

Probably Not For Long

I think there’s a big problem for Olin Wright’s vision of positive class compromise. When countries try to do it, it works for awhile but eventually the capitalist class erodes and defeats it during hard times. We can look at places like Finland or Sweden for good examples of this problem.

In both cases, financialization and the neoliberal era beginning in the 1970s squeezed capitalist profits. Capitalists responded to this by shifting the range of possibilities to the left on the above graphics.

Why? Imagine what happens if you continue moving to the right on the previous graphic, past where the graphic ends. As workers get so powerful that the economy transitions into full socialism, capitalist interests precipitously decline. Basically they fall off a cliff. And so, capitalists always have a reason to resist social democracy. They know it could lead to full socialism.

A Better Transition

Where does this leave us? I think we need to achieve socialism by overcoming the transition trough. And among our options, I think (a) is still the best. How can we speed up the socialist transformation so that socialist movements don’t get swept out of office? And how can we do it in a way that doesn’t resort to authoritarian methods?

My own view is that we do so through a combination of methods: establishing alternative institutions within the shell of capitalism, political education and solidarity, mutual aid and assistance programs for hard times, and advocacy of larger, social democratic programs to meet basic needs. Through a combination of methods, we can change the rules, build expertise, and achieve political power in such a way as to have much of the new society coming into place at the same time it’s needed.

Postscript: “What’s the Point?”

Some readings might think much of this discussion fanciful. If we haven’t even achieved social democracy yet, why worry about the problems in transitioning from it to socialism?

Clarifying our goals and methods helps us determine how to organize now. Other countries have tried the transition, and some foundered on the transition trough. We can learn from their mistakes and try different ideas.

If certain programs work, we can focus on the effective ones. And any program we propose should be with an eye toward transforming economic ownership and control, not merely short term relief. It makes sense to prioritize ideas – like Medicare for all or workers’ cooperatives – that restrict the reach of the market.