So, social democracy and taxes? I’m going to approach this topic from a couple of angles. First, I’ve made some efforts in the past to distinguish between progressivism, social democracy, and socialism. But I want to say more about this. I think these terms, albeit unsettled, pick out importantly different political philosophies. Taxation forms an entry-point to thinking about these differences.

Second, Elizabeth Warren recently worked her way into a bit of a jam. She’s struggling with how to pay for Medicare for All, a set of bills proposed by Pramila Jayapal and Bernie Sanders that would create a robust, comprehensive, world-class single-payer health insurance system. Warren worked her way into this jam, I’ll argue, because she’s a progressive who backed her way in to endorsing a social democratic idea. The news endlessly covers the entire kerfuffle, but I think the press sees this less as a philosophical problem than a policy problem. On the contrary, I think it’s primarily a philosophical problem opening up over the topic of taxes.

Progressivism, Social Democracy, and Socialism

What’s the difference between these three views? I’ve teased it out a bit previously in posts on Elizabeth Warren and Julián Castro. Here’s what I had to say there about the respective political philosophies of Sanders, Warren, and Castro:

Sanders is a social democrat, maybe or maybe not a progressive, and not a democratic socialist.

Warren is a progressive, but neither a social democrat nor a democratic socialist.

Castro is maybe or maybe not a progressive, but neither a social democrat nor a democratic socialist.

I think that’s cryptic enough for a start. We might be able to learn a bit about the differences by looking at the policies of these three candidates. So, what does all that mean?

Progressivism

I trace US progressivism to its roots in the early 20th century. It’s a middle and upper middle income movement, notably a reaction to growing corporate power. As it happens, big business grew sharply in power at the turn of both of the 20th and 21st centuries, thus explaining the return of the ‘progressive’ label. Progressives center process reform (e.g., ballot initiatives and referenda, recall of politicians from office, et al.), government efficiency and services. They call for means-tested programs aimed at the neediest, and they want to run a clean government by stamping out corruption.

If this all sounds like the Elizabeth Warren campaign that’s because Warren’s a textbook progressive. One, she repeatedly talks about corruption and process reform. And, two, she wants to harness growing wealth to benefit the needy. As opposed to, say, eliminating wealth and putting working class and poorer people in charge. We’ll return to that topic shortly.

Social Democracy

Social democracy started as a gradual route to socialism via the electoral process and existing institutions. It was, in short, a thesis about the transition from capitalism to socialism via elected representatives cumulatively appropriating economic institutions and power in the name of the public. See, for example, Eduard Bernstein‘s The Preconditions of Socialism.

But that’s history. ‘Social democracy’ doesn’t really mean anything like that now. At this point, social democrats want to mobilize a broad base of people to create a system taking care of everyone’s basic needs under capitalism. And social democrats think we can do so while reducing income inequality, easing the marginalization of certain social groups, et al. In a social democracy, the state provides universal access to basic needs like health care, housing, education, food, water, et al. And the system draws upon a large base of working class people, unions, and so on to achieve these gains.

What’s the difference between this and progressivism? Social democracy centers working class people and other marginalized groups. Not merely as the people who benefit from need-based programs, but as the protagonists in movements. Working class people are literally the ones organizing and achieving the gains. Progressivism, by contrast, is grounded more in terms of advocacy, charity, or even noblesse oblige. It’s about wealthier people organizing to use their privileges to benefit others.

A Side Note on Social Democracy and Socialism

As a quick aside, there’s also the issue of how social democracy differs from socialism. But I think the answer is simple enough, at least in its broad outlines. Whereas social democracy preserves the capitalist system in some form, socialism doesn’t. It abolishes it. Whereas the social democrat might advocate for public ownership of certain basic public needs, the socialist goes further and advocates for public ownership of the entire economy.

Social democrats like Bernstein wanted to use social democracy as a transition point to socialism, but the end point of socialism defined the program. They still shared with Marxists the ultimate goal of socialism. And that ultimate goal is what social democrats now reject, and it’s why they’re no longer socialists. They’re no longer interested in doing for other sectors of the economy what they want to do for basic needs and public goods.

In current times, social democrats sometimes adopt proposals for those sectors like sectoral bargaining, shared board seats for workers, et al. that give workers a greater share in capitalist wealth. But the greater share depends on maintaining capitalist wealth in order to work.

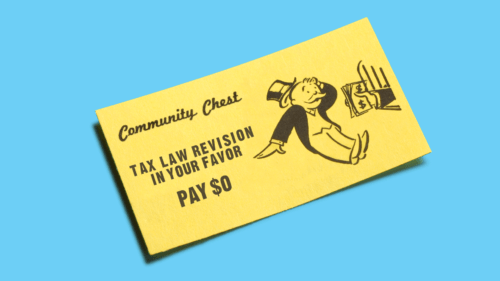

Social Democracy and Taxes

Well, then. Great. There are differences between the three views. Got it. Why does it matter, and what’s it got to do with Elizabeth Warren and her plans to pay for Medicare for All? Does this mean Warren doesn’t advocate for social democracy?

It’s tough for Democrats to talk about taxes, especially to talk about taxes on middle income people. For that reason, we might use tax policy to talk about what separates these views. And at the moment, the competing statements from Sanders and Warren regarding how to pay for Medicare for All makes the biggest splash in the middle income tax pool.

Sanders admits the need for tax increases on middle income Americans to pay for the program. And he does so directly. Not only at debates, but also in his list of payment options for the program. To be fair, he plays it a bit coyly. He shrouds the tax increases within other tax plans targeting the wealthy. But at the end of the day, when you ask him he’ll say that we need a broad tax base to accompany Medicare for All. Probably through imposing something like additional payroll taxes to make the program work its best.

Warren doesn’t admit this. She talks circles around the question of middle income tax increases, and she goes out of her way to try to pull the impossible (and arguably inadvisable, see below) “wealthy people alone should pay for it” rabbit out of her hat.

That Which is a Plan for Sanders is a Problem for Warren

Why?

This all flows neatly from their commitments to social democracy and progressivism, respectively. Sanders the social democrat wants to build a world where a broadly democratic state provides for basic needs, owns certain public utilities, and builds support from a working class and middle income base. Warren the progressive wants to encourage the flow of capital while using surplus wealth to provide services for the neediest.

The Sanders program requires a broad tax base to work, because working class and middle income people are central both to building and sustaining the program. The Warren program not only doesn’t require a broad tax, but actively avoids one. To someone like Warren, taxes on middle income people involve directly taking money from those who are supposed to benefit from the noblesse oblige of the wealthy. Thus, she thinks middle income taxes are counterproductive. She’s going to try as hard as she can to avoid it.

Hence, the political problem Warren faces now on how to pay for single-payer health insurance. She’s endorsed Medicare for All, a social democratic program that only a broad social democratic tax base can pay for. But she’s no social democrat. And she totally opposes social democratic tax policy. And hence, why this is no problem at all for Sanders. As I said above, he’s got an entire list of options for funding the program.

Practical Benefits to a Broad Tax Base?

Here’s a final question: Are there any benefits to a broad tax base of the sort social democrats tend to prefer?

Maybe.

With any social program, we face a risk of political opposition. Public health insurance creates an additional risk. Meaning that conservative, libertarian, wealthy, et al. interests might lobby for reduced health care under the Jayapal-Sanders Medicare program. Why? In order to save money and reduce their tax burden.

Of course, every major social program faces a version of this problem. The current Social Security and Medicare programs face the same worries. And yet, generally we don’t reduce Social Security and Medicare benefits. Not only that, but for the most part we don’t really come close to reducing those benefits.

One reason these programs are relatively secure is that they draw on a broad tax base and benefit a broad range of people. When we all pay and we all benefit, it’s tougher for criticism to gain traction. These kinds of programs really aren’t a bad deal for the wealthy, and they’re an actively good deal for almost everyone else.

Consider, by contrast, the progressive move of taxing only the wealthy, or only certain businesses, in order to benefit a relatively small group of people. Corporate interests have a playbook for defeating programs like this: demonize the small groups of beneficiaries, build resentment among everyone from wealthy to middle income people, and then chip away at the programs or eliminate them outright. Moreover, since progressivism needs the wealthy classes to generate the wealth it uses to pay for its programs, those programs remain especially vulnerable to the playbook.

Warren and Medicare for All

And so, there’s the issue of Elizabeth Warren and Medicare for All. I suspect she’s…OK with the program. She needs to cut into the Sanders base to win the nomination, and endorsing Medicare for All helps her do it. But I don’t think it’s a disingenuous move for her. The program would help her accomplish her goal of serving the needy. However, ultimately, I think she’d prefer something else. And her progressivism leads her in these different directions. In the shorter term, she’s going to continue struggling to come up with a payment plan because she philosophically rejects the one payment plan that works.

Where will she go from here? She might endorse full Sanders-style social democracy on this one issue and support a broad tax base. Alternatively, she might release a single-payer plan with benefits far less generous than those Jayapal and Sanders offer (i.e., she might just offer people the current Medicare plan without the strong Jayapal-Sanders improvements). And, for a third alternative, she might just reject Medicare for All outright and revert to something more like what the other candidates advocate.

We’ll find out.