In the recent edited collection Social Reproduction Theory, Tithi Bhattacharya and others make timely contributions to Marxist feminism.

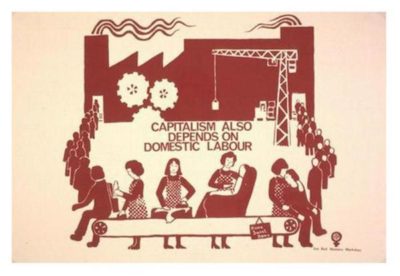

Their main message is that rather than commodities, labor plays a central role in both production and the social reproduction of society. Contrary to dual-system theory, Bhattacharya and others see social reproduction theory as offering a unitary account of production and reproduction. Unlike many early Marxists, however, they center labor and class conflict in explaining both.

I’ll take a closer look at Bhattacharya’s introduction to the volume, as well as her essay in the collection. I think her work, in particular, best captures the spirit of the approach.

Social Reproduction Theory

In her intro, Bhattacharya defines ‘social reproduction theory’ broadly. She’s focusing not narrowly on specific issues of gender or work, but rather all the processes that reproduce the worker and the society of the worker. We’re talking here about everything from education to care to getting a good night’s sleep and eating a good breakfast.

She points to the centrality of labor to all of these things. And she argues for a conception of labor and the economy that includes not just production of commodities, but also all these kinds of reproductive labors.

Changing our thinking in this way comes to impact a wide range of things the left talks about and does. It pushes us to study how education serves to create a compliant workforce, but also creates possible models for change (as Susan Ferguson’s essay shows). It pushes us to investigate the crisis of failing social reproduction in the neoliberal era (as Nancy Fraser invites us to do). And it pushes us to question the approaches taken by theorists of ‘intersectionality‘ (David McNally).

How Not To Skip Class

I think these points come together most fruitfully in the essay Bhattacharya herself contributes to Social Reproduction Theory (‘How Not to Skip Class,’ pp. 68-93).

She thinks the left’s narrow focus on production leads it to a too restrictive definition of ‘working class’ and a too limited perspective on the subject of leftist change. As she tells the story, the left considers only people currently working for a wage. And, on even narrower understandings, only those who produce value.

In contrast, Bhattacharya argues we should define ‘working class’ more broadly. It should include anyone who has ever worked in such roles, paid or unpaid. It should also include anyone who has ever worked in any role involved in social reproduction, from teachers to nurses to unpaid caretakers or housewives and househusbands.

Why? She thinks this will open up the left to building more fruitful ties to social movements not immediately grounded in organized labor – everything from climate change or racial justice movements to movements for better schools. She sees all of these as working class movements, but believes leftist theory sees them as ‘outside’ of working class organizing.

For my part, I find some thorny problems in how Bhattacharya applies her main theoretical points. It’s true enough that the movements she cites have working class components. But, as currently practiced in the U.S., they’re often centered on the concerns of management or petty bourgeois interests. Plenty of other theorists have said as much.

The challenge for leftists is to bring a working class angle to these movements. And simply defining all of them as already working class doesn’t get it done, in my view.

Final Thoughts

The real strength of her article is the careful, accurate way she reasons through Marx and Marxist traditions. She’s quite right to point out that being ‘working class’ isn’t just about currently holding a working class job. On that point, we agree completely. My own definition of ‘working class‘ includes, e.g., unemployed workers, retired workers, and spouses of workers for these same reasons.

For working people, the background conditions of life form a constant site of class struggle. We don’t just get jobs by showing we ‘add value‘. Rather, we constantly fight over the social necessities that produce the value of our labor-power. As leftists, we therefore fail to see how class struggle works when we don’t recognize this.

The capitalist system values different workers in different ways. And it even values the same workers differently across time. To collectively fight to increase our standard of living requires us to adopt a broader notion of the worker and the social movements the worker cares about.

Bhattacharya sees all this. Social reproduction theory provides us with tools to draw these insights and make them explicit in our modern world. Class struggle isn’t just about workers and bosses fighting on the job over working hours or pay. And so, we need to think more dynamically about who’s in the working class and about the scope of working class struggle and politics.

We can apply social reproduction theory, in this sense, to DSA campaigns around issues like housing or trans liberation. In both domains, we fight for the concerns of working class people that go beyond the job site.