A possible war with Syria rarely dominates the headlines, but it just as rarely strays too far from them. The situation has persisted since the Syrian civil war began in 2011. How did this happen, and where will it lead?

I’ll briefly review the history before diving into the policy details. The U.S.’s Syria policy fits well into the bipartisan foreign policy consensus, but it also reveals fault lines between Donald Trump and the Democrats, among other areas.

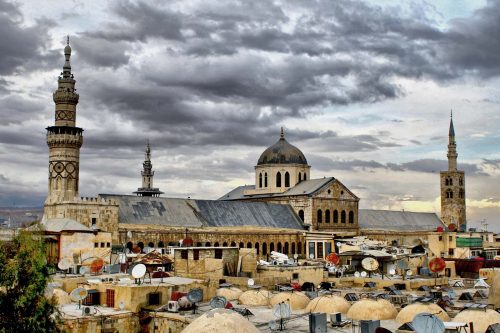

Ba’athist Syria

The Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party has ruled Syria for more than half a century. But the al-Assad family looms large over the entire period: 30 years under Hafez al-Assad and 20 more under his son, Bashar al-Assad.

Aside from its dynasties, the main thing we know about the so-called ‘socialist’ Ba’athist movement is that it’s not socialist. No one but the most foolish of tankies would deny this. To provide more detail, the al-Assad family seized Syria in the late 1960s and early 1970s from Ba’ath leaders who actually did have ties to pan-Arab socialism and leftist movements – see, e.g., Mansur al-Atrash or Salah Jadid. They ended those ties, some immediately and some gradually. Any remnants of socialism in the Syrian state today are there in name only.

Yes, the transition from Hafez to his son Bashar offered reason for optimism around issues of democracy and humanitarianism – if not socialism – but the optimism didn’t last long. Whatever was left, the civil war extinguished in 2011.

Syrian Civil War

The Syrian civil war followed the broader Arab Spring movement, specifically the Tunisian Revolution in late 2010 and early 2011. But in a Syrian context, al-Assad’s shift away from the left and toward neoliberalism paved the way for a sharp spike in inequality. It led to a split between a Damascus-based ownership class and an immiserated class living throughout the country. Added to inequalities between an Alawite Muslim minority ruling class and diverse religious populations of Muslims and non-Muslims, it produced tensions al-Assad couldn’t keep in check.

The civil war itself began as a series of political protests. Inequality was the deeper cause, but the proximate cause was preemptive over-reach by the al-Assad government. The state incarcerated and tortured political dissidents and students – among other groups – to try to prevent a Syrian branch of the Arab Spring.

It didn’t work, and al-Assad attempted to backpedal with a series of concessions. That didn’t work either, and defections and the creation of the Free Syrian Army followed. Things spiraled out of control from there, leading to battles and then international intervention. Further escalation of the war in 2013 led to a power vacuum and ISIS and U.S. involvement by 2014. Over the last six years, it’s settled into a situation where the al-Assad government maintains control over most of the country. But the death and displacement tolls are catastrophic, and both ISIS and the Turkish military remain active in parts of the country.

U.S. Foreign and Military Aid

I’d recommend consulting Wikipedia’s overview and timeline of the U.S. role in Syria. It’s surprisingly helpful.

Insofar as Americans think about these things, the standard view is that the U.S. supplies funds and weapons to ‘moderate Syrians’ or to ‘Syrian opposition’ to the al-Assad government but that the U.S. isn’t engaged in active intervention.

That’s mostly false. The U.S. provided funding and weapons from nearly the beginning of the civil war. And it provides those funds and weapons to a wide range of groups. In explicit policy and rhetoric, the U.S. supports the ‘Free Syrian Army.’ But it’s not too clear precisely what that term refers to. On paper, it was a group of military officers looking to overthrow al-Assad while changing the structure of the country as little as possible.

The trouble is that the group is more a reality on paper than on the ground. The original Free Syrian Army fell apart quickly, and the term is now used by a wide array of organizations united only in their commitment to receiving U.S. funding and weapons. This is, in fact, a frequent problem with U.S. aid in the context of civil wars.

Yes, we see it time and again. The U.S. encourages or even fabricates ‘moderates’ and funds them – ‘moderates’ who happen to be very sympathetic to U.S. interests in the region. Once it’s clear these groups have little grassroots support, they fold or they’re outright defeated by groups less amenable to U.S. interests. The Deng government in Vietnam is the most obvious – and most tragic – example of this issue. On that topic, I’d highly recommend Noam Chomsky‘s work.

U.S. Military Intervention

And then there’s the other problem: the U.S. does engage in active intervention in Syria. And it’s been doing so since about 2014. Obama ordered airstrikes early in the conflict, with ISIS rather than al-Assad as the main target. Through January 2015, the U.S. carried out 70 airstrikes. It all operated under the name Operation Inherent Resolve. And while the operation ebbed and flowed over the years, it conducted nearly 35,000 total airstrikes in Syria and Iraq.

Thus, ‘will the U.S. go to war in Syria?’ is the wrong question. It’s been at war in Syria for 6 years, and the Obama administration – not the Trump administration – started it.

Of course, there’s another aspect of this debate – the one over Obama’s so-called ‘red line‘ in Syria and subsequent ‘failure’ to intervene against al-Assad. That was a much narrower debate focused specifically on regime change. Yes, the Obama administration showed some restraint, especially as compared to an extreme foreign policy hawk like Hillary Clinton or Lindsay Graham. But this hardly means the U.S. didn’t go to war.

It did.

YPG

Much of what the U.S. is doing in Syria is, therefore, business as usual. The closest it’s come to an exception is perhaps its more recent support for the Syrian Democratic Forces. Why? The Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) leads the military component of the SDF.

In theory, the YPG is a broad anti-fascist front. It’s composed mostly of ethnic Kurds opposed to al-Assad, but especially opposed to ISIS. It focuses almost all its fighting against ISIS. While not obviously ideological, the YPG incorporates leftist elements in practice.

The best example of leftism within the YPG is the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) – an explicitly feminist group of women fighters with links to both libertarian socialism and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The link is via ‘Jineology‘, which – among other things – promotes a Kurdish feminist understanding of social science as a form of gender oppression.

The YPG International also includes significant leftist components and members.

The U.S. has little love for the democratic and popular elements of the YPG. It promotes and utilizes their military resources because they’re the best in the region. And especially because they hate ISIS. Nevertheless, the U.S. has no problem with undermining the SDF and YPG on its more positive aspects, and would increasingly do so if it were looking like YPG were winning the war.

Restraint and Withdrawal

While the bipartisan foreign policy consensus has long operated in the U.S., we’ve seen some cracks and fissures over the course of the last decades. The two most recent U.S. administrations – Obama, and then Trump – are not at the extreme edge of hawkish foreign policy. Above, I highlighted one way Obama’s actions fall short of those preferred by extreme hawks like Hillary Clinton and Lindsay Graham: he didn’t actively push for regime change in Syria.

Donald Trump took this newfound ‘anti-war’ streak a bit further, announcing a withdrawal of U.S. troops from Syria in December 2018 and partially carrying it out in October 2019. And while troop levels have ebbed and flowed since, Trump generally uses a lighter hand in the region than Obama.

Motives vary on these actions from Obama and Trump. But both issued challenges to the bipartisan foreign policy consensus. Obama was committed to a scaled-down realism that made for a much less aggressive stance than that preferred by, e.g., George W. Bush. Trump’s foreign policy is some kind of semi-coherent isolationism. But in practice it often amounts to a light hand.

Neither Obama nor Trump grounds their less aggressive foreign policy elements in anything like international solidarity, leftist principles, or peace. Any anti-war inclination will drift away if and when circumstances change. And so, it makes sense to endorse their actions in certain specific cases. But leftists should never trust either of them.

Foreign Policy 101 Series

This is the fifth post in Base and Superstructure’s Foreign Policy 101 series! Here are links to the other four:

North Korea

Israel-Palestine

Bolivia

Venezuela