Isaac Asimov published his science fiction detective novel The Caves of Steel in 1954. One of the detectives was a robot. That’s the twist. Lots of sci-fi fans know Asimov for his robot stories, and Asimov invented the word ‘robotics‘. The Caves of Steel became Asimov’s best-selling book to that point in his career. Asimov followed up with the Robot Series: The Naked Sun (1957), The Robots of Dawn (1983), and Robots and Empire (1985).

But that’s just the history. It’s not what this post is about. The Caves of Steel is less a detective story, or a robot story, than a sociological story. Let’s talk about that.

Automation and Jobs

Horace Gold told Isaac Asimov he should write a robot novel. Sure, Asimov wrote robot short stories in the 1940s, but why not a full-length novel? And Gold wanted a novel about robots taking human jobs. Despite his own protestations to the contrary, Asimov knew how to write history and sociology. This is the guy who wrote the Foundation Trilogy, after all.

Asimov set The Caves of Steel a couple thousands year in the future in a world where Earth regresses to enclosed Cities (with-a-capital-C). Everyone lives under domes in mega-cities. Why? Extreme overpopulation and strained resources. Earth automates most of the food system, from farming to producing to delivering to serving. And there’s a strict job classification system where one succeeds, fails, and gains or loses resources through a standardized evaluation system.

Lose your job? Well, you’ll still live. They’ve got something in place kinda like a dystopian UBI system. It looks a lot like what Boots Riley cooks up in the film Sorry to Bother You. You’ll eat and have a place to stay, but that’s about it.

In an early scene, a police department staffer loses his job to a robot. R. Sammy, the robot, is a very basic model with a goofy grin and an obnoxious habit of following only very literal instruction. Earth declassifies the staffer and puts him on basic assistance. Asimov trots him out later in the novel to useful effect. And so, it’s not subtle.

Not a New Issue

It’s obvious enough automation isn’t a new issue. In fact, it’s been central to capital-labor conflict for decades. And 1950s and 1960s race and class conflicts put it square at the center. That Asimov wrote The Caves of Steel at this precise juncture shouldn’t surprise anyone, but it does anyway.

We might learn a bit about our current world if we study this era. Here’s one quick lesson. US social programs, particularly LBJ-era Great Society programs, failed in large part because they didn’t focus much on issues of automation and job loss. The federal government recognized a wide variety of rights of black Americans in the workplace. But black Americans missed many of these benefits because manufacturing sector employment quit growing at exactly the same time.

Nostalgia Politics

The Caves of Steel begins with a conversation between a detective and a robot. The robot took a staffer’s job, as I mentioned above. And lest anyone miss the significance, Asimov lays it on thick. There’s obviously a broader social issue at work here. Robots threaten humanity with obsolescence. At least, they appear to. Humanity responds with, you guessed it, nostalgia for the past. It’s not exactly ‘Make America Great Again’, though it’s not exactly not that, either.

However, robots don’t really threaten humanity, either today or in the sci-fi future. At least, not directly. Broader social forces threaten us, and robots are merely the face of it in particular times and places. Asimov labels the nostalgia nerds ‘medievalists’ in a bit of fun wordplay. These medievalists idolize…the 20th century! Since they’re a couple thousand years in the future, we’re medieval to them. They want to return to a pre-robot era, which, of course, isn’t really pre-robot at all.

As a result, the nostalgia doesn’t make much sense. We’ve automated away jobs for decades. Marx catalogued the impact of technological change on the value of labor-power even in his own era. But, second, humanity enclosed itself under giant domes in The Caves of Steel. These are the caves of steel of the book’s title. Consequently, everyone suffers from extreme agoraphobia. They can’t go outside! The medievalists couldn’t return to a pre-robot world from the mere fact they can’t live daily life outside of the Cities.

Asimov, of course, knows these things. He made the medievalist position silly for the same reasons we think Trumpist nostalgia is silly. Asimov shows how these eminently silly missteps come from real, albeit wildly misdirected, concerns.

Accelerationism and Redemption

The story of The Caves of Steel centers on a murder mystery. An Earthman kills a descendant of the human population that colonized other worlds centuries prior. Way back before Earth retreated into Cities. Those people are called Spacers. The human and robot detective work to solve the crime.

The Spacers have a city (with-a-little-c) of their own, just outside the City of New York. And it’s called Spacetown, appropriately enough. From Spacetown, the Spacers push an accelerationist project. They see Earth’s rising catastrophe, and they want to push Earth away from nostalgia and toward renewed space colonization. They try to do it by pushing Earth deeper into medievalism.

And so, this is sort of standard accelerationism. By pushing Earth deeper into its foolishness, the Spacers heighten the problems and tensions involved in Earth’s overpopulation and precarious food supply chain. The only way out, so they think, is to colonize space. Thus, Earth’s regressive elements will redeem themselves and secure Earth’s future.

There are legendary problems with accelerationism, and I think it’s probably Asimov’s biggest misstep. We know these things rarely turn out well, and we know regressive groups rarely redeem themselves in this way. Instead, they fall deeper into mistrust or other problems.

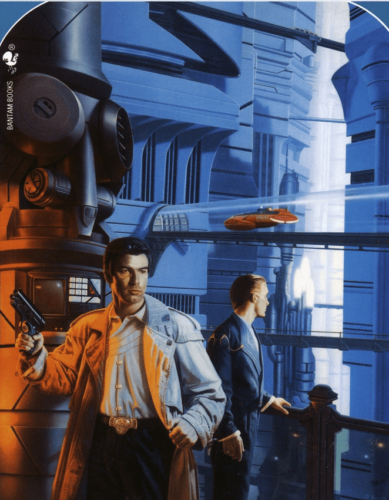

The Caves of Steel: A Film?

US politics fail to explore a lot of the material here. Automation, jobs, reactionary politics, misplaced nostalgic sentiment? It’s all here.

Why wouldn’t someone turn The Caves of Steel into a movie? I’d watch it.