This rather weighty tome from David Graeber and David Wengrow – The Dawn of Everything – got lots of attention upon its late 2021 release. I’ll call them the Davids. Some of the attention arrived due to the untimely death of David Graeber. He brought us a number of modern anarchist-leaning leftist classics. Topics range from ‘bullshit jobs’ to rules and debt.

But this book also arrived in a timely way. Insofar as the public hears grand historical narratives, they come from sources like Jared Diamond or Steven Pinker. Diamond and Pinker present a certain ‘standard narrative’ of history. For them, history proceeds in stages: from simplicity to complexity, from agriculture to industry, from ‘primitive stateless society’ to empire, and so on.

The Davids question all this in The Dawn of Everything. And they do some other things. Let’s see how it works out for them.

Mythbusting and Politics in The Dawn of Everything

So, the Davids do a lot in The Dawn of Everything. But they hit two key points again and again.

First, they engage in a detailed mythbusting project. They lay out popular historical grand narratives like those I mention above. And they poke holes in them. Lots and lots of holes, by way of lots and lots of examples.

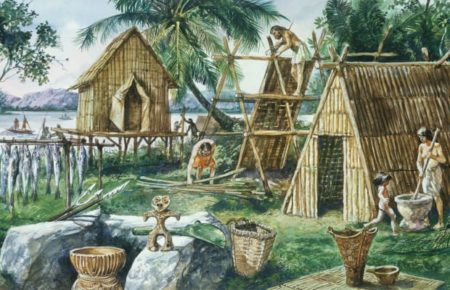

They point to early cities in Africa, the Middle East, and South America. These cities seem quite complex and yet had few – if any – major structures of authority. They show pretty conclusively that agriculture took thousands of years to develop. It hardly stands out as the quick ‘agricultural revolution’ that many people infer. And Indigenous societies seemed to move back and forth between agricultural and hunter-gatherer modes. They didn’t proceed in a straight line.

Second, they vigorously defend human freedom, and they find far more egalitarian societies in history than others find. On this count, they look at many so-called ‘primitive’ forms of society. They also look at societies that perhaps had no state at all. And they even manage to flip the question a bit on the standard narrative. Rather than asking where inequality begins, they ask where we lost our freedom to determine our own politics.

Did the Davids Succeed?

On the first part of the book – the mythbusting project – the Davids wildly succeed. The point isn’t entirely new. Some anthropologists poked holes in the grand narrative long ago. But the popular literature never caught up. The Davids step in to provide that for a lot of people. And so, I have to give them an A+ on mythbusting.

The second part of the book – the political project – comes out a lot more mixed. The Davids unearth the interesting possibility of more democratic societies throughout human history. They raise the point that people revolted against empires without society falling apart. Maybe some societies did carry things on well enough – even better – after the so-called ‘collapse’ of their civilization.

Then again, maybe not. The Davids don’t provide a lot in the way of definitive evidence for this, only tantalizing possibilities.

But their biggest fault is that they seriously overstate the role of human agency in all this. Yes, people have options. People can come together and decide what kind of society they want. And, insofar as others fail to notice this, they’re correct to point it out. But the Davids way too quickly dismiss social forces as playing a guiding role. Modes of production don’t directly determine our politics. But they do provide a lot of structure. And they make some routes much easier than others.

The Davids lose sight of that in their pursuit of human agency as a leading factor.

Rousseau and Hobbes

There’s one final thing worth mentioning here, and I left it to the end on purpose. Much of the discussion of The Dawn of Everything – especially among philosophers – concerns a little story the Davids tell about Hobbes and Rousseau (and, more so, a story later folks tell about them). I left it to the end because it’s mostly a side issue.

Leave it to philosophers to miss the forest for the trees.

As the Davids put it, there are two basic narratives about history and the ‘state of nature.’ The first one – traced to Hobbes and accepted by many on the right – says that early societies were chaotic and war-like. People couldn’t get along, and they had to give all power to the state in order to move along the stages of civilization. The second one – traced to Rousseau and accepted by most people to the left of the GOP – says that early societies floated in a kind of primitive bliss. To advance, they had to create a state. But the state carried inequality as a side effect. And we can’t undo that inequality without also tossing out civilization.

Perhaps that’s an accurate reading of Rousseau, but perhaps it isn’t. It doesn’t matter much for the Davids’ main argument. It’s true the Davids try to use it to claim heavy Native American influence on the Enlightenment. That’s intriguing – even plausible – and the Davids do a good job listing Native critiques of European authoritarianism. But they fall well short of showing its influence on the Enlightenment.

However, the main argument of the book – there’s a historical grand narrative with lots and lots of flaws – holds up well enough regardless of the wisdom of using Rousseau and Hobbes to make the point.