Not long ago, I read a book on the writing and ratification of the U.S. constitution. I found it useful, and after I read it I wanted to move along to primary sources. It doesn’t get more primary than the The Federalist Papers, a collection of essays many Americans know. For anyone who doesn’t know, it’s a set of essays in favor of the constitution from three of its key defenders (Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay).

So, the thing about these essays is that historians, political scientists, and others have written a ton about them. I’m not repeating all that, nor am I really citing it. I’m doing something much less formal. As I read The Federalist Papers, I found a couple of the essays especially useful. That’s all.

Let’s take a look.

Federalist No. 6

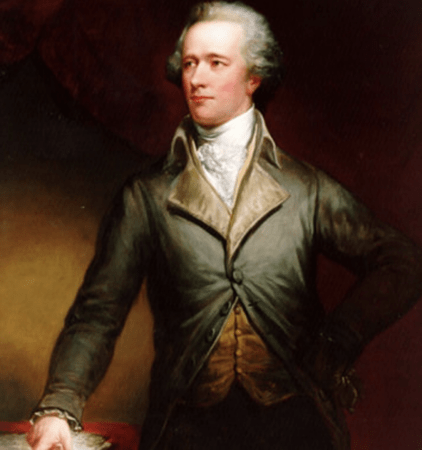

So, there’s a lot of material in The Federalist Papers worth thinking about. But Federalist Nos. 6 and 10 caught my attention. Hamilton wrote Federalist No. 6, and he wrote it in defense of a strong national government. In truth, Hamilton thought it should be even stronger than what the constitution laid out.

He defends a strong national government as the only way to ensure peace among the states. Anti-federalists argued, by contrast, that the country didn’t need a strong national government to keep the peace. Rather, they claimed trade relations backed by the Articles of Confederation sufficed. Hamilton responds by pointing out that republics fight wars as often as any other kind of state. And he does so by citing a small army of historical examples. And so, even if the U.S. turned into a sea of tiny republics, those republics would find reasons to fight each other.

Hamilton gives us a nifty argument, and it’s even a convincing one on the merits. If I can find a problem with the argument, it’s that it proves too much. Supposing that republics fight wars as often as monarchies – perhaps even more often – wouldn’t a U.S. united under the constitution just fight a bunch of external wars, even if it doesn’t fight internal ones? Maybe the states wouldn’t fight each other, but wouldn’t they fight Native Americans, the Spanish and British, and so on?

Hardly a hypothetical. It’s exactly what happened after the U.S. ratified its constitution. The U.S. entered a state of war more or less right away, and it has fought wars ever since.

Federalist No. 10

James Madison raised an entirely different set of issues in Federalist No. 10. Out of all The Federalist Papers materials, it probably attracted the most attention in the history and political science literature. Even Marxists (and their opponents) write about it. But I’m not trying to do scholarly work here, so I’ll set that aside. I’m writing about first impressions of the text as a layperson.

So, Madison writes about the problems of factions and divisions within republican society. He worries that factions – contrary interest groups – might threaten liberty and the public good. Here’s his argument as I read it: To deal with factions, we can attack their causes or mitigate their effects. The causes of factions are permanent and ‘natural,’ so we can’t take the first route. However, we can mitigate their effects by creating a large republic with competing interests and divisions of power. This will prevent any one faction from dominating. Since the constitution provides for exactly this, then we should ratify the constitution.

The Federalist Papers and Madison

A couple of things stand out to me. First, Madison comes very close to a leftist view on this. He takes contrary interest groups as fundamental to politics. And he even grants that inequality in property drives these factions and divisions. Any leftist could accept that much. Of course, contrary to Madison, leftists don’t think this is ‘natural.’ On the contrary, leftists think we can attack the causes of factions by getting rid of private property.

Second, Madison turns republican political philosophy on its head. Contrary to Montesquieu, he argues for a larger republic over a smaller one. Philosophers thought small republics work better because only a small society could govern on popular consent. By contrast, Madison argues that only a large republic can avoid the problem of the tyranny of the majority. Only a large republic can prevent any one faction from gaining full control. In doing so, Madison makes an original contribution.