Housing is a top issue in Iowa City politics.

It’s not difficult to see why. We’re a growing college town of about 75,000 people. And while social and economic change have hit many parts of rural Iowa hard, we’ve weathered the storms relatively well. Iowa City faces more problems of gentrification than universal despair.

However, the prosperity of Iowa City pushes out many long-term and/or working-class residents. For one, the rent is too damn high. In addition, rising property values push less wealthy homeowners to foreclosure and prevent tenants from buying their first homes. Many move to Coralville or North Liberty. And as even those places see the same problems, some move further out to Hills, Tiffin, or Oxford.

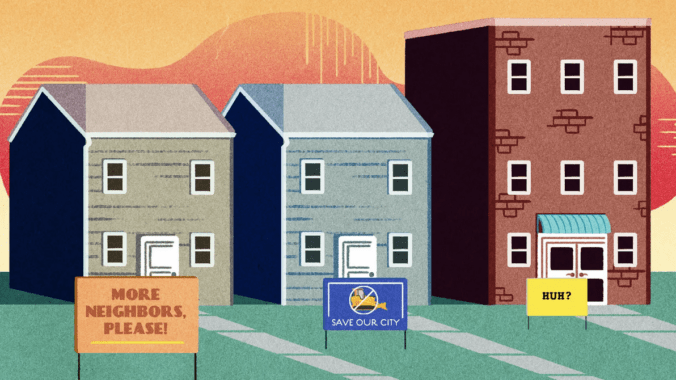

Back in Iowa City, our housing debates degenerate into a false dichotomy between NIMBY and YIMBY views. Neither view serves the interests of working people and tenants.

And so, getting past the NIMBY vs. YIMBY false dichotomy is essential to understanding housing from a leftist perspective that’s centered on workers and tenants.

The NIMBY side

We’ll start with the NIMBY side. ‘NIMBY’ stands for ‘not in my backyard,’ but most readers already know this.

NIMBYs don’t like development, especially in their own neighborhood or city. Many really dislike things like affordable housing or homeless shelters. Most tell a story about ‘crime’ to justify this.

Very few people explicitly own the label, for the obvious reason that it was created as a pejorative. But it does describe some people well. Nathan J. Robinson lists a few helpful examples.

We see it in Iowa City, especially around opposition to homeless shelters or service homes run by nonprofits. Often we see it from pockets of small business owners, especially in and around downtown. Frankly, I find more NIMBYs among these small business types than among regular residents, but I suppose YMMV.

A laundry list of NIMBY policies includes a ton of ideas affordable housing research doesn’t support. This list includes universal single-family zoning, the dismantling of public housing, the lack of requirements for affordable units, and so on.

That the NIMBY is the enemy of working people is painfully obvious, so obvious that it opens an opportunity for shenanigans among the opposition…

The YIMBY side

And that takes us directly to the YIMBY side of the false dichotomy. Unlike the NIMBY, many YIMBYs are proud to wear the label.

‘Yes, in my backyard.’ Get it?

In short, a YIMBY is one who holds oneself up as more enlightened than the NIMBY. They often master the language of social justice to portray the NIMBY as a backwards, tacit racist.

And that is why we have so many YIMBYs in Iowa City. We’re full of wealthy progressives. And many are drawn to any idea with the kind of radlib potential we find in YIMBYism. Plenty of people in Iowa City love to hold forth about how they’re ‘smarter than the average bear.’

Less racist, too.

But that’s enough about the term and the psychology behind it. Let’s talk about the policy ideas.

YIMBYs want to increase housing supply, full stop, often by any means necessary. They see ‘affordable housing’ as a simple problem of supply and demand to solve with more supply. They think this will, in turn, lower rents and purchase prices.

Intuitively, it makes sense, at least at a broad, programmatic level. The YIMBY often pounds the table and declares it “Econ 101.” And, indeed, it does represent a good high school level understanding of economics.

Problems with YIMBYism

But, of course, as with econ beyond high school, it’s not that simple. There are two key problems with YIMBY reasoning.

First, not all ‘supply’ is the same. Developers often prefer to build luxury housing, which does little or nothing to lower rents and prices. And they often tear down more affordable housing in order to do so. And so, this kind of supply just drives more gentrification.

To get around this, governments have to intervene heavily to create the right sort of supply, i.e., housing in reach of working people. We do have a few tools to do this (e.g., LIHTC), though these tools are usually expensive and inefficient.

But there’s a second, deeper, problem. In focusing so intently on supply, YIMBYs ignore demand. In claiming the mantle of “Econ 101,” they ignore literally half of Econ 101! The YIMBY assumes that demand stays roughly the same and doesn’t affect price.

The problem is that this assumption is false. YIMBYs have in mind a fixed set of people looking to rent or buy housing to live in. But a great deal of housing demand comes from landlords, the finance industry, and other bad actors.

Tools that increase housing supply – from multi-family zoning to accessory dwelling units (ADUs) to other ideas – also increase demand. They do so by making land and properties more valuable to investors. The issue of price, then, is a question of whether the increase in supply is larger than the increase in demand, in addition to the question of whether they can market the units as luxury units.

YIMBYs avoid that question. We see this over and over again, even in Iowa City, where local YIMBY groups do a great job proposing ideas to increase supply, but punt on the question of demand.

NIMBY and YIMBY: United for Property Value

The YIMBY pounds the table and accuses the NIMBY of ignoring the research. And that’s mostly accurate. NIMBYs do typically ignore research, because the research isn’t relevant to their goals. They want to resist a certain kind of change because they don’t like it. They don’t need to read a study to figure that out.

But YIMBYs cherry pick the research, accepting studies that show good results for their ideas and ignoring or explaining away research that shows bad results.

The reality is that the research evidence is mixed.

It shows a landscape where sometimes YIMBY ideas reduce prices, and sometimes they don’t. Some studies show a favorable impact of ‘upzoning’ on housing price, while others show an unfavorable impact. Minneapolis ended single-family zoning, and it has had mostly positive results so far. Changes in Chicago have had negative results. ADUs serve to add property value, benefit wealthy homeowners, and create ‘second class citizens’ in neighborhoods, but might lower prices when focused on the right sort of units.

In short, we have to evaluate these ideas on a case-by-case basis. The YIMBY, by contrast, often dismisses unfavorable results with the ‘No True Scotsman‘ fallacy, i.e., by claiming that the bad examples weren’t full versions of the policy.

Sure, Jan.

At their heart, both NIMBY and YIMBY ideas serve homeowners and property values above all. What divides NIMBY and YIMBY is mostly just the details of their class politics. NIMBYism serves the interest of wealthy homeowners, along with some of the upper middle professional class homeowners. YIMBYism serves the interests of developers, landlords, and especially homeowners who want to become small-time landlords.

The NIMBY’s main goal is to keep the neighborhood small and quiet by limiting density. And the YIMBY’s main goal is to make properties more attractive to capital.

Centering Tenants and Workers

Neither of these perspectives align to the interests of tenants. And we see the harsh realities of this in Iowa City politics.

It’s not really in the interest of tenants to increase property values. In many cases, it’s in the interest of tenants to lower property values, so long as it happens by things like more public control and dampening investor demand rather than by crime or property deterioration.

Many readers know by now that I spent several years working on a tenants union. I learned many lessons along the way. Here’s one of the most important: every perspective in the ‘affordable housing’ debate, from NIMBY to YIMBY, represents capital, landlords, and/or homeowners, not tenants.

Working people and tenants aren’t well served by either NIMBY or YIMBY logic or policy. The NIMBY is actively harmful to tenants, while even ‘affordable housing’ nonprofits or coalitions serve tenants indirectly at best, and usually not at all.

And so, from our perspective, the NIMBY and YIMBY sides look similar. It’s a false dichotomy.

For workers and tenants, we need something more like this: tenants unions with a strong rent strike tool at the local level, rent control and low-income housing subsidies at the state level, and robust, mixed-income public housing at the federal level.

We’re a long, long way from any of that. But all of us can work on it.

Leave a Reply