The trick to reading a Robert Caro biography? He writes about places more than people. And, above all, he writes about power. I pointed to this feature in a post on Caro’s book series The Years of Lyndon Johnson. But before Caro wrote about LBJ, he wrote about Robert Moses and New York. I’ll say a word here about The Power Broker: a book about how one builds (and then loses) power in a major US city.

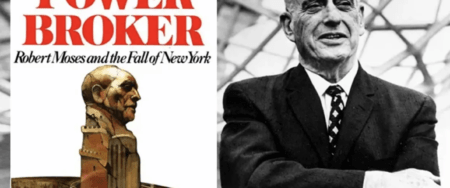

Robert Moses

Caro’s book follows Robert Moses through his career – from his early idealistic and progressive phase to his rise to power and then to his fall. But who was Robert Moses? Why should we care?

That very question, in part, forms its own answer. Few people know Moses, despite the fact he built much of New York’s park, highway, and public housing infrastructure. In fact, Moses probably created more infrastructure than anyone in the history of the planet. Plus, he did so mostly without holding elected office. And with little in the way of public attention, other than praise in the New York press. Neat trick, right?

Moses started as an idealist and dreamer. He had a vision as early as the 1910s for a system of public parts in New York – city and state. And he entered politics quite early in the form of civil service reform. Tammany Hall crushed him.

Moses learned his lessons, gradually building power to the point where he became the world’s master builder. Eventually, he lost it all, retiring largely alone and bitter.

The Power Broker

As Caro tells the story, Moses rose to power by filling power vacuums. He used small and seemingly unimportant offices to take over larger and larger segments of the New York infrastructure world. And he used his vast knowledge of legislation and process to literally create some of the agencies he oversaw. Furthermore, he used these skills to make it extremely difficult to remove him from power. Some of his appointed offices held long terms, and others didn’t even allow the New York mayor to touch him at all. In any situation where he had the slightest vulnerability, Moses played competing politicians off of one another to stay in charge.

But power increasingly corrupted Moses. By the 1940s and 1950s, Moses held basically all infrastructure power in the city through his use of a public authority (Triborough Authority). But his actions had long since ceased to serve the public. Or even, for that matter, Moses’s own ideals or dreams.

Moses’s parks and highways destroyed much of the city’s nature sights, and progressive reformers had turned on him by the 1930s. Most of the Moses highways caused rather than solved traffic problems. And they practically eliminated the potential for lower cost mass transit. His slum clearance and public housing policies were so over the top racist that the journalists who praised him eventually caught wind.

If that wasn’t enough, the massive amounts of money Moses moved through public authorities contributed to the huge funding shortfalls faced by schools and hospitals.

The End of Robert Moses and Lessons Learned

The gradual loss of his reputation emboldened Moses’s enemies. Eventually, Nelson Rockefeller defeated Moses and ran him out of office.

But that didn’t happen until 1968. From the time Moses lost his idealistic dreams, he spent several more decades in power. And he spent about a decade in power long after he lost any real support among the public. He did so by consolidating power, putting together the interests of various groups (developers, construction unions, et al.), and making it incredibly difficult to remove him.

What struck me about the book even more than the lessons in building and losing power was the glimpse we get of the kind of person who builds power in this way. Moses comes off as a person singularly driven by power and action. He poured his entire self into large-scale building. Not to mention all the politicking needed to do that work. By comparison, he had little time for family or friends that wasn’t directly tied to work.

I have a hard time understanding this type of person. If that’s what it takes to be The Power Broker, I’m surprised the role has many applications. And yet it does. We can find, I think, plenty of examples of The Power Broker in the corporate world, in particular.

I still don’t really get the appeal.