John Steinbeck wrote about two thefts of the land in The Grapes of Wrath. As readers, we know Steinbeck as the classic author who wrote eloquently about the second theft, the banks’ theft of the dying Oklahoma countryside from its tenant farmers. But many of us know less than we should about the first theft.

Let’s take a look.

The Second Theft

Theft of the land appears and reappears in The Grapes of Wrath. But I think it appears most explicitly in Chapter 5. This is one of Steinbeck’s ‘inner chapters‘ – chapters not directly concerning the the Joads (or the Wilsons), but indirectly commenting on the broader situation.

In Steinbeck’s telling of it, “when the monster stops growing, it dies. It can’t stay one size.” He’s talking, of course, about the banks. To feed their need for profits, the banks have to evict the unprofitable tenant farmers. The banks have to find a new economic model.

They do. And the new model is a familiar one from our consideration of primitive accumulation. The banks cleared the land of its farmers and hired wage laborers. Using this method, they created an industrial agricultural proletariat on land formerly farmed by semi-feudal sharecroppers.

That’s what happens to the Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath. Formerly a sharecropping family, the banks run them off. The Joads head to California because there’s no place for them among the new proletariat of the Oklahoma Dust Bowl.

Lost Profits

Why was the land no longer profitable for the banks? The short answer, of course, was the Dust Bowl itself. That’s the proximate cause. But there’s a longer answer, and it’s one requiring us to look at broader economic trends. The sharecropping system in the U.S. was built around the growing of cotton and other labor-intensive crops, particularly after the end of U.S. slavery. Slavery provided agricultural masters with an extremely profitable system they struggled to duplicate. Sharecropping was their alternative.

Harshly working the land for a single crop depleted it and made it unprofitable. The banks, responded, of course, by stealing it from its tenant farmers. Perhaps the deep irony here is that none of this saved it. Proletarianizing the land was part of a plan to make it less sustainable, to quickly extract profit from the land before its final death.

Those of us watching current climate change debates could learn some things from this story.

The company men of Chapter 5 of The Grapes of Wrath freely admit all this. “‘But you’ll kill the land with cotton,’ the tenant farmer says to him. ‘We know. We’ve got to take cotton quick before the land dies. Then we’ll sell the land. Lots of families in the East would like to own a piece of land,'” came the reply.

Indeed they would.

The First Theft

But all this talk of banks stealing land from tenant farmers leaves out the first theft!

Not that Steinbeck ignores it. His characters discuss it at the margins. In the conversation between the company man and the tenant farmer, the farmer cites his own history with the land: “Grampa took up the land, and he had to kill the Indians and drive them away. And Pa was born here, and he killed weeds and snakes. Then a bad year came and he had to borrow a little money.”

And there you get both thefts together in a narrative. Did Grampa ‘take up’ the land, or did he just take it? It depends. Someone stole the land from the ‘Indians,’ i.e., Native Americans. Who stole it? If not ‘Grampa,’ then the U.S. government.

The tenant farmer compares Indians to weeds and snakes, analogous enemies of the tenant farmer and occupants of similar places in his racist background. Later, in Chapter 19, the tenant farmer explicitly distinguishes between theft and what ‘Grampa’ did: “In Hooverville the men talking: Grampa took his lan’ from the Injuns. Now, this ain’t right. We’re a-talkin’ here. This here you’re talkin’ about is stealin’. I ain’t no thief.”

No thief?

The Grapes of Wrath

Like many Americans, I read The Grapes of Wrath in high school. Also like many Americans, I never re-read it until now. I suppose I’ve watched the film a couple of times.

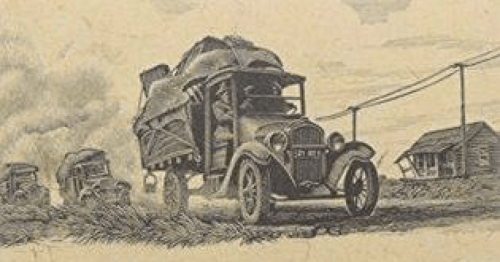

But I picked it up again a few weeks ago. I remembered the Joads: the death of Grampa, the regional dialect, the clouds of dust and wasted fields, the journey across the country on Route 66, the false promise of California.

What I didn’t remember was the way Steinbeck wove the story of the Joads together with Dust Bowl Oklahoma and its discontents: faceless banks and their company men, tenant farmers and homeless wanderers, failing shop owners and usurious car salesmen.

Steinbeck was at his best when writing not about his characters directly, but about the material culture of the Dust Bowl. On its own – robbed of people – an Oklahoma home fades into a bleak landscape. Without the close bond with its farmer – thrust into the hands of the banks and its hired hands – the land becomes homogeneous, bleak, and impersonal. Steinbeck shows in a particularly clear way how the introduction of a rogue element – the banks – tears it apart.

A number of thoughts come to mind.

– Greed of the banks .

-Short sighted profit taken from the land without the rotation of crops for future years. (Land dies).

-Strength & determination of the human spirit.

– People – especially Poor /& deprived have much more strength when they work together / collectively.