The political left doesn’t know what to make of Venezuela, just as it doesn’t know what to make of a lot of foreign policy issues. Ken Livingstone asserted Hugo Chávez should’ve killed the oligarchs. That’s one view. George Ciccariello-Maher, a more careful analyst, also lapses into overheated rhetoric. But if there’s anything like a left consensus, it looks like this: vague critique of the current administration standing next to critique of any US-backed war. As Michael Walzer would surely say, it’s the vague consensus at work.

I’d like to get less vague. I’ll give an overview of the situation in Venezuela, and I’ll honor a bit of the spirit of Livingstone’s flippant remark without reproducing its content. What’s the insight here? It’s this: the Bolivarian Revolution, ’21st Century Socialism’ in name, recreated many of the problems of 20th century socialism in practice. And I’m talking here about the social democratic varieties, not the Leninist or Stalinist ones.

But all things in good time. First there’s our point of departure. Everyone agrees things are fucked up in Venezuela, but they don’t agree how or why. What’s fucked up? Why did it happen? Will Venezuela fix it?

I’ll tackle some of these questions on the way to our destination.

What Led to Hugo Chávez?

Let’s start with what everyone probably knows. Hugo Chávez was first elected president in 1998, and he served until his death in 2013. Along the way, he won three more elections: 2000, 2006, and 2012. His presidency greatly changed Venezuela, but how so and how did it happen?

For a topic so rife with disagreement, the facts are fairly clear. Venezuela was a two-party representative democracy from the late 1950s through the early 1990s. The two parties – Democratic Action (Acción Democrática) and COPEI (Partido Socialcristiano) shared power in a parliamentary system. There were minor parties – like the Democratic Republican Union (Unión Republicana Democrática) – and the occasional left-wing populist leader – like Luis Beltrán Prieto Figueroa – but this was a pretty stable system.

While this system was great for the country’s centers of power, it was lousy for most ordinary Venezuelans. Corruption reigned throughout the period, but got noticeably worse after a recession in the late 1980s. On top of the corruption, President Carlos Andrés Pérez accepted IMF loan money and accompanying austerity conditions, leading to decreased social spending, increased poverty, and mass protests. Pérez survived multiple coup attempts, including one led by…Hugo Chávez. What he didn’t survive was a corruption scandal and ensuing impeachment in 1993.

Rafael Caldera won the 1993 election, but he did so at the head of a ‘National Convergence‘ rather than as a member of either of the two parties. The system had been totally discredited. Caldera’s Convergence was more an ad hoc grouping than a political party. He led a cross-ideological coalition of the center-right to the Marxist left. It’s unlikely he’d have ever made this work, but a new recession, banking crisis, and additional round of IMF loans and austerity ended any dim hope.

Hugo Chávez and the New Order

So, that’s the background prior to Chávez’s 1998 win with more than 56% of the vote. More than anything, Chávez offered something different. He led an electoral group called the Fifth Republic Movement (Movimiento Quinta República), and he made no pretense of working within the old order. He campaigned explicitly on a pledge to write a new constitution, fight poverty, and fight corruption.

And he did most of what he said he’d do. That’s much of the story of why he remained in office for 15 years.

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela

Immediately after his 1998 election, Chávez put in motion a constituent national assembly to write a new constitution. The process and outcome were unusually participatory and democratic. Among other things, the new constitution established: Indigenous political representation, restrictions on non-Indigenous patenting of Indigenous knowledge and products, protections for women, and public rights to food, education, housing, and health care. It added new environmental protections and established mechanisms for oversight and recall of government officials.

That’s the good. But the constitution also strengthened the president, sometimes drastically. It lengthened terms and term limits, and it gave the president numerous means of working around the legislature.

What we have here is a frequent theme of the Chávez administration: a stronger presidency with stronger popular participation, largely at the expense of legislative and lobbying power. And bold moves, like renaming the country the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

Poverty

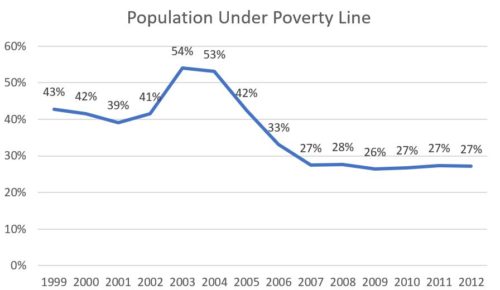

As for the second promise, Chávez delivered big. Poverty dropped from 1999 to 2013. The only exception was 2002-2003, during a coup attempt and deliberate economic sabotage. Often poverty dropped steeply during this period. Here are the overall poverty levels.

Source: Center for Strategic and International Studies (https://www.csis.org/analysis/venezuelan-drama-14-charts)

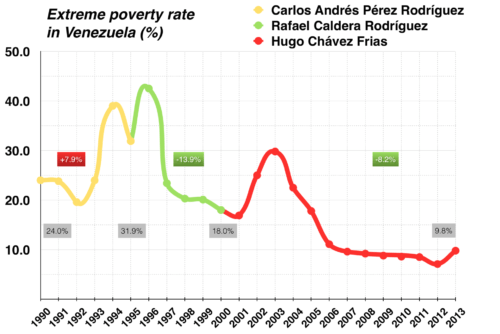

And to zoom in a bit closer on those most struggling, here are extreme poverty levels.

Source: Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Venezuela)

And so, Chávez was wildly successful on this promise. Once the 2002-2003 events, and 2004 recall referendum, were settled, he cut poverty by about 40% and extreme poverty by about 50%.

If poverty reduction were the whole of it, that’d be impressive. But it’s not. Along with poverty reduction, Venezuela massively increased social support and spending. From Plan Bolívar 2000 on through the various Bolivarian missions, Venezuela built a massive social democratic support infrastructure that made life less difficult even for many of those who remained in poverty.

Corruption

This one’s a mixed bag. On the one hand, Chávez ended the corrupt system. But on the other, he generated a new system with new forms of corruption.

At its heart, the Bolivarian project was a social democratic one built at times around cooperation between domestic industry and the government and at other times cooperation between different segments of the state. Chávez established patron-client relationships with these groups, particularly the state-owned oil and natural gas company, PDVSA.

There’s a long history of literature critical of Chávez in the domestic Venezuelan left, though the literature itself is complicated and difficult to evaluate. And, of course, much of it’s in Spanish. As an introduction to (a small part of) that literature, I’d recommend reading this English translation of an article from El Libertario, along with a retort by Ciccariello-Maher.

Evaluating Bolivarian Venezuela

How did Chávez do? He did most of what he said he’d do: replace the old regime, fight poverty, and fight corruption. The corruption piece was a mixed bag, but the rest was very successful.

The big picture? These were social democratic successes. Chávez used the tools of progressive taxation, wealth transfer, and government services to improve lives. He promoted popular involvement in politics, though always in line with his own power. The successes and failures of the communal councils are noteworthy here.

The rest of the Bolivarian program – the transformative, socialist parts – were far less successful. Despite repeated attempts to democratize and diversity the economy, nothing ever worked well enough. The project included everything from co-op businesses to worker-owned factories to other social enterprises. For the most part, these programs failed due to political patronage, mismanagement, or lack of prioritized support.

For an overview of these programs in their earlier years, I’d recommend Gregory Wilpert’s book Changing Venezuela By Taking Power.

The Current Crisis in Venezuela

I’ve spent far more time on the history than perhaps readers expected. Why? Because I think the difficulties and failures of the Bolivarian project – especially its lack of economic diversification, excessive reliance on executive authority, and strong opposition from the US and Venezuelan elites – largely account for the crisis of the last 5 years or so.

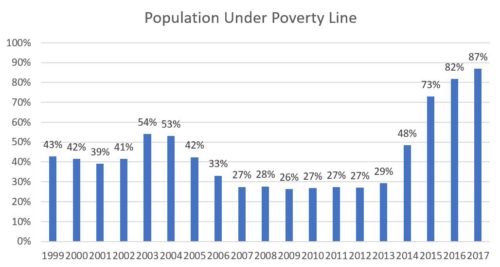

So, what happened? Chávez died in 2013 and was succeeded in office by Nicolás Maduro. Maduro won a (likely fair) election in 2013, and then won a (likely much less fair) re-election in 2018. Many of the gains up to 2012 and 2013 have been totally wiped out. And then some. Nobody knows exactly where the poverty rate is at, but some groups have tried to estimate. Here’s an example.

Source: Center for Strategic and International Studies (https://www.csis.org/analysis/venezuelan-drama-14-charts)

I could post more of these, but readers probably get the point.

What else is happening? How about: shortages of food and basic necessities, runaway inflation, massive cuts in social spending, and an attempted coup by a legislative leader named Juan Guaidó.

What The Fuck Happened?

Everyone’s got a story for what happened. Maduro cites economic sabotage by the US and Venezuelan elites. The opposition cites Maduro’s mismanagement and ensuing capital flight.

Who’s right?

In some sense, they both are. But they tell only part of the story. The clearest cause of the crisis is the drop of oil prices beginning in 2014. That’s what led to the drops in social spending and broader social problems. And why did oil prices drop? Internal rivalries among OPEC members – particularly Saudi Arabia’s push for greater oil production – did a lot of work here.

While those things were largely out of Maduro’s control, they don’t tell the whole story. For several reasons, Venezuela wasn’t well prepared to handle a drop in oil prices. First, Venezuela needed to diversify the economy and develop popular, democratic institutions for handling tough times. They started this project, but they made much less progress than they needed to make.

Second, Venezuela yielded too much power to the president, and the Bolivarian movement depended far too much on the personality of Hugo Chávez. Maybe they’d have been able to hold it together had Chávez lived, but he didn’t live. Maduro never had the popular support and political skills Chávez had. And even if he did, the issue remains that a powerful presidency sits in tension with a democratic movement.

And third, Venezuela still had layers and layers of corruption, particularly as expressed through a patron-client system Chávez established. This was most noticeable in state-owned industries, but also in areas where social democracy ran through cooperation with domestic business owners.

And so, both Maduro and the opposition appeal to issues that are very much real. But they don’t give us the full picture.

Postscript: Sources

Venezuela is a particularly difficult country to read about. For those of you in the US, there’s the general difficulty with finding good news coverage of any non-US country. We’re an unusually insular country. But when we’re talking about Venezuela, there’s a deeper concern: most of the news is terribly biased.

The main principle here is balance. Yes, read the New York Times for their coverage of Venezuela, but balance it with a clearly pro-Chávez/Maduro source like Venezuela Analysis. Democracy Now‘s coverage is generally very good. I’ve also linked a number of books and articles throughout this post worth checking out.

What To Read Next

Why not check out some of the other posts in the Foreign Policy 101 series? The other three cover: Bolivia, Israel-Palestine, and North Korea!