As some readers know, I’ve written several posts on Agile as a business term and theory. I’ll link to those past posts with these two links. I wanted to follow up on one issue, namely the term ‘cargo cult Agile.’

What is cargo cult Agile? Is it a problem and, if so, how can companies avoid it?

Cargo Cult Agile

Often, the business literature focuses on whether what a company does counts as ‘Agile.’ For consultants and various ‘experts,’ Agile looks like big money. Why? Because they use their mastery of the topic to power their brands and win clients. Largely in the consulting industry’s quest to enforce boundaries do we find the term ‘cargo cult Agile.’

And so, we ought to proceed with a certain amount of caution.

With that said, here’s the basic idea behind the ‘cargo cult agile’ label. A company practices cargo cult Agile when it follows Agile rules or structures on paper – and in its org chart – without really internalizing the mindset or values people think Agile embodies.

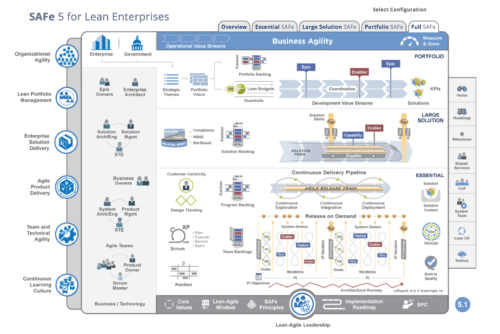

That’s a broad critique. And, as I’ve noted previously, Agile is itself broad and slippery. While the basics of Agile remain pretty simple, things get more complicated when we move to Agile implementation. Programs like SAFe Agile, in particular, carry lots and lots of rules and features. From the Scrum method of organization to specific roles – from Scrum Master to Product Owner to Release Train Engineer – to things like sprint cycles or PI Planning, SAFe Agile is an incredibly complicated system.

Don’t believe me? Here’s how its own advocates visualize it.

Image source: https://www.scaledagileframework.com

Got all that? I didn’t think so. And if that’s not enough, it comes in four different versions (configurations).

And so, the term ‘cargo cult Agile’ often refers to getting lost in the weeds. They might spend so much time trying to implement ideas as written that they forget the point. At its most apt, the term criticizes a kind of mindless rule-following.

Is Cargo Cult Agile a Problem?

Despite its origins in the consulting industry, cargo cult Agile does happen from time to time. Perhaps it happens more often than companies want to admit. For one, it’s difficult to apply systems as complicated as what you see in the graphic above. Companies should think critically about which parts of that system work and which don’t. They should also focus on basic, core principles. Like the ones we find in the Agile Manifesto.

However, I think many users of the term miss where it’s all actually found. They see it as a product mostly of large, conservative organizations. Sometimes that happens. I’m sure some companies really do implement Agile because it’s the easiest path to being top-down and bureaucratic while also cashing in on the ‘Agile’ name. Some even turn the system into a kind of white-collar Taylorism. They allow middle managers and project managers to drive these things.

But that’s hardly the core of the problem. When mindless rule-following of this sort rears its head, it tends to happen in companies that try to force Agile onto employees whose work it doesn’t fit. And we see that most often outside the tech industry. Agile doesn’t always fit tech companies, but it’s mostly customized to those companies. When companies outside tech try to implement it – especially when the work isn’t collaborative or team-driven, doesn’t fit into sprint cycles, et al. – they struggle.

The result? Companies – and their employees – narrowly follow the rules to avoid running afoul of anyone powerful. But they either reject the underlying principles and values, or the rules themselves block the implementation of those principles and values (because the work doesn’t fit).

Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition

And so, yes. cargo cult Agile happens, and it’s often a problem. Sometimes companies implement Agile for nefarious reasons, like intensifying work or deskilling labor. But it happens more often, by contrast, when a (usually non-tech) company tries to fit a rigid model onto work where the model doesn’t really fit.

How should companies implement ideas like Agile? The first step, of course, is that they should ask whether the model really fits their work. If the answer is “no” or “probably not,” then they shouldn’t implement it. Perhaps they can borrow a few good ideas from it, but they shouldn’t try the full model. But if companies do find the model fits – or fits well enough – I’d recommend thinking about it along the lines of skill acquisition. In particular, I find the Dreyfus skill acquisition model helpful.

When a person first learns a new thing, they often need to follow the rules very closely. As they become more proficient – when they reach the stages of competence and proficiency according to the Dreyfus model – then they can – and should start violating or discarding rules. As the person develops, they work beyond analytical and rule-based modes of thought. They act more holistically, and eventually on intuition alone.

It’s keeping that point in mind – that one needs to soon start modifying or even rejecting rules as one becomes more proficient – that companies should think about. That’s what will help them avoid cargo cult Agile.

I’m the author of the article at extremeuncertainty.com that you mentioned. Thanks for the mention and the link. I definitely agree that SAFe is an over-complex and prescriptive beast that is unlikely to help organisations on their agile journey.

If you want to know more about how agile ideas can be applied even in non-technology environments, I would recommend reading two books: “A Leader’s guide to Radical Management” by Steven Denning, and “Management 3.0” by Jurgen Appelo. For a more radical and historical rethinking of organisation theory in these contexts, the book “Rethinking Organisations” by Frederic Laloux is astonishing.

Thanks, Leon! Those are helpful starting points. It can be difficult to find resources aimed outside/beyond tech.