Contemporary racial justice movements often focus on white women as both ally and enemy. They’re both lead consciousness-raiser and target of activist opposition.

On the negative side of the ledger, white women have bolstered the Jim Crow system. See, e.g., Elizabeth McRae’s Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy. They call the police on black people for going about their everyday business. See, e.g., Permit Patty and BBQ Becky. They strategically use emotions for racist impact and sometimes engage directly in violent assault.

These issues, of course, aren’t new. The case of Emmett Till is the usual case study when talking about historical precedents.

On the positive side of the ledger, white women often make up most of the audience at racial justice events. This is especially true at ‘Racial Justice 101’ events. They are also at the front lines on any campaign for racial justice within white-dominated economic or social spaces, such as workplaces or schools.

The reasons for this are complicated. But one common theme is that racial justice organizers, particularly black and other POC organizers, tend to perceive white women as simultaneously a group harmed along one axis of oppression (i.e., gender), which gives them a certain empathy for oppressed non-white Americans, but also advantaged along another (i.e., race), which provides them with incentives to bolster white supremacism. The accuracy of this perception is an issue I’ll set aside, though I think it’s accurate enough to proceed.

This all brings us to Trump. There’s overwhelming inertia, within this broader discussion of race, to place Trump’s win at the feet of white women. Outlets from the New York Times, to the Washington Post, to Emily’s List, to the Huffington Post, and the Huffington Post again, have all pointed to this group as the decisive factor in electing Trump.

How could white women vote for this man who abuses and insults women of all races? How could they vote for a misogynist?

So, why did white women elect Trump?

*Drum Roll*

I’ll make a different move here.

They didn’t.

White Women and the 2016 Election

By any measure of white womens’ votes, Hillary Clinton outperformed Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign. In terms of racial and gender combinations, they were literally the only group more likely to support Hillary Clinton in 2016 than Barack Obama in 2012.

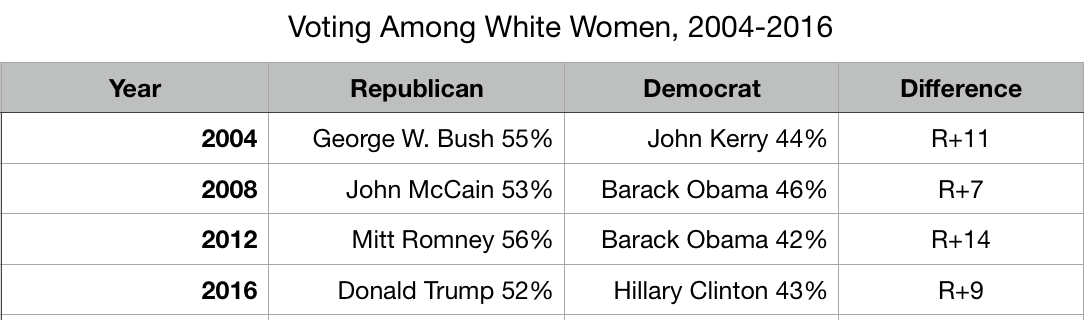

Here’s a table showing how white women have voted in the last four presidential elections.

Source: CNN Exit Polls, 2004-2016

In terms of the raw vote numbers, Clinton did noticeably better than Obama in 2012, slightly better than John Kerry in 2004, and almost as well as Obama in 2008.

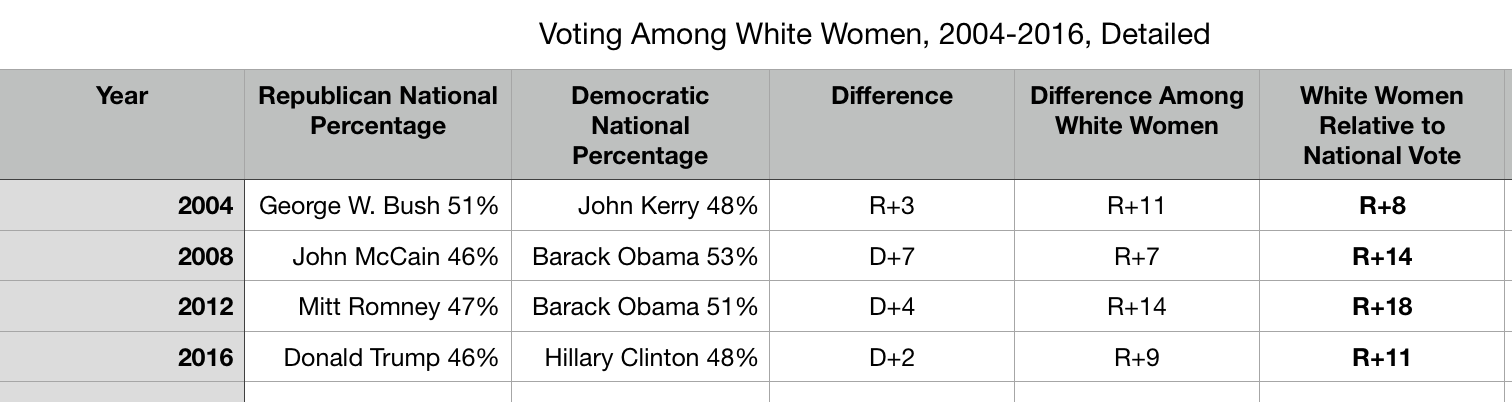

But even this information understates the point. Let’s look at the vote among white women in each of the last 4 elections, relative to the national average.

Look at the column on the right side. This is a much better measure. It’s a measure of how white women voted, relative to how everyone voted as a whole. Note that from 2004 to 2012, they were becoming more Republican with each election cycle. They were 8 points more Republican than average in 2004, 14 points in 2008, and 18 points in 2012. Hillary Clinton convincingly disrupted that trend.

Based on prior trends, we should’ve hypothesized that the Democratic candidate in 2016 would perform 20-24 points worse among white women than the national popular vote. Given that Clinton won the popular vote by 2 points, she should’ve lost white women by 18-22 points. Instead she lost by 9.

Thus, Clinton over performed expectations by about 10 points. Had she repeated this movement with other demographics, she’d have easily won the election.

White Men

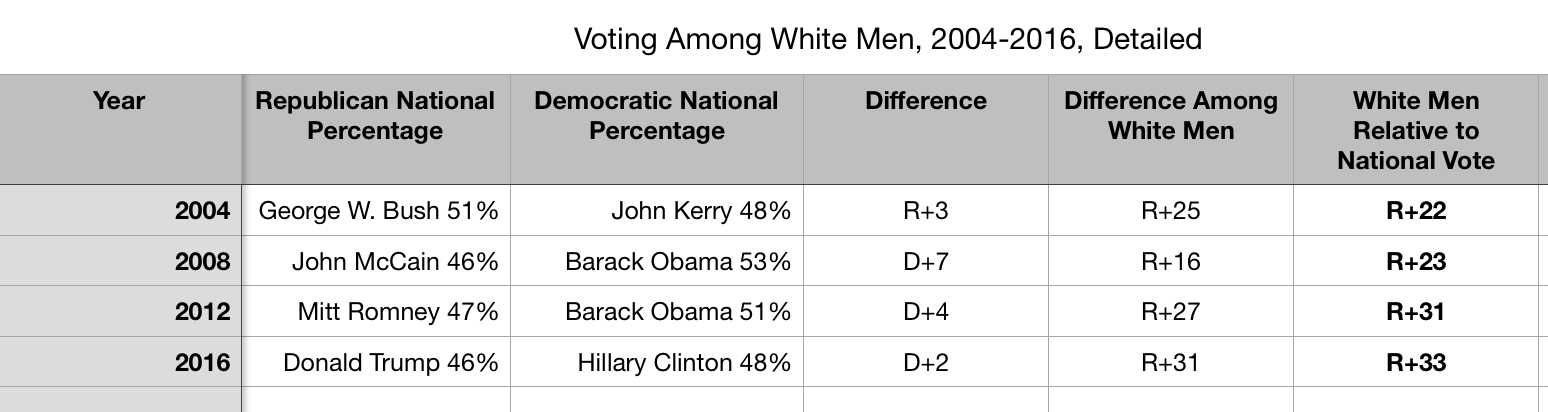

For a point of comparison, here’s the same information for white men.

Again, look at the right column. From 2004 to 2012, white men also became increasingly Republican relative to the national average. The difference is 2016. In 2016, white men continued to become more Republican, whereas white women did not.

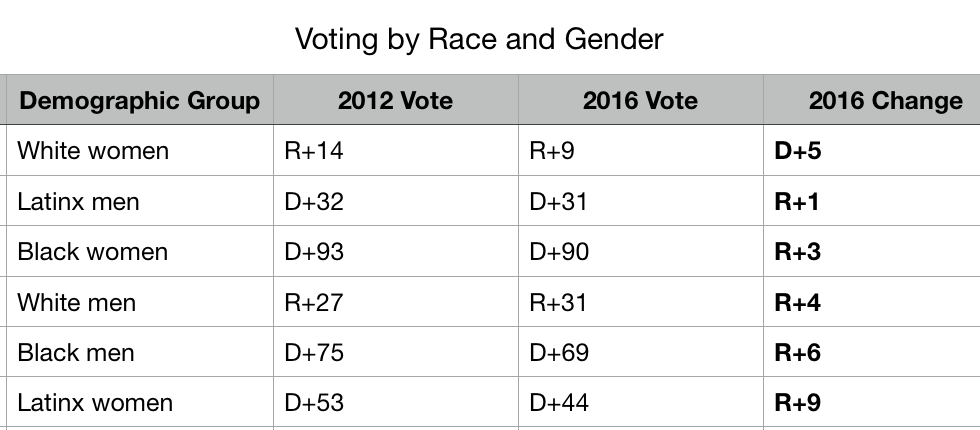

Let’s expand the comparison to non-white voters of all genders. Here’s how each combination of race and gender shifted from 2012 to 2016.

What this table shows is that Clinton lost ground, relative to Obama, with every other group. Hillary Clinton outperformed Obama among white women, and only among white women.

As I pointed out earlier, Trump’s base is composed of white men. Especially white men who make more than $50,000 per year and live in rural areas, among other features. White women, especially those with college degrees, are not a major part of Trump’s base. They were not the decisive factor in electing Trump.

Explanation

Let’s recap. From the data, white women didn’t elect Trump. In fact, Clinton over performed among this group. It’s this, namely Clinton’s over performance, that needs an explanation. Why did Clinton win ground with white women, but not anyone else?

To this mystery, I offer three possibilities:

1. Clinton was running to be the first woman president. White women bonded with her over a shared identity, shared experiences, and a shared sense of being held back from achieving a highly visible status. She shared these things with white women in a way she didn’t with most women of color. Thus, she performed well among white women for some of the same reasons Obama increased black voter turnout in both 2008 and 2012.

2. Clinton targeted college-educated white women with her campaign. She campaigned almost exclusively to the core Democratic base. But in the few instances when she veered from this narrowly tailored campaign, she attempted to win votes among college-educated white women who were appalled by Trump.

3. College-educated white women wanted to distance themselves from racist and misogynistic Trump supporters. And so they voted for Clinton in greater numbers than they voted Democratic in prior elections. The white women who voted for Trump were more explicitly racist than those who voted for Romney, but there were fewer of them overall.

Electoral Implications

One reason people talk about the electoral behavior of white women, particularly insofar as Democratic leaning PACs and interest groups (e.g., Emily’s List) are the driver, is brazenly electoral. Democratic-leaning political groups have decided that they’re likely to succeed by guilting, shaming, and browbeating people into voting Democratic.

In light of the data above, this strategy will quickly encounter diminishing returns. In 2016, Democrats probably maximized the share of the vote they’re going to win using these methods. I don’t see them improving on that result in 2020.

Overall, white women are trending Republican. The 2016 election disrupted that. But as soon as Republicans nominate someone less obviously offensive than Trump, and as soon as the Democrats nominate someone who isn’t running to become the US’s first woman president, it’s likely that these prior trends resurface.

This is kind of a problem for Democrats. It’s a problem in the same way that the decline in black voter turnout, once Barack Obama was no longer on the ballot, was a problem for Democrats.

Electoral Solutions

If Democrats want to secure the vote of white women (and, for that matter, other voters), they’ll have to seriously rethink their approach. They need to think more about the material interests of voters, and they need to drop the moral haranguing. Campaigning to low wage workers, people who lack access to abortion and other forms of health care, and people who face the worst of misogynoir, misogyny, and rape culture is something that could, over time, build a new voter base.

The benefit of this kind of campaign is that it doesn’t appeal to the white woman qua white woman. It appeals to her in terms of material interests she often shares with non-white women and others. By contrast, laying guilt trips on voters is going to fail.

Toward a Deeper Explanation

While I think I’ve made a solid case, I suspect some readers aren’t satisfied. Even though Clinton over performed among white women, the fact remains that this is still a Republican-leaning group. Why?

In an article recommended to me by a friend, political scientist Charles Tien presents data showing a longer-term trend of white women becoming more Republican. The trend dates to the 1960s, and is a prior continuation of the data I’ve presented above. Tien proposes racial resentment as the explanation, particularly in light of Civil Rights legislation from the mid to late 1960s. He particularly ties racial resentment to support for Trump in the 2016 Republican primaries.

Kate Manne, a philosopher, recently published a fantastic book called Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. Manne provides a general account of misogyny, but she also applies this account to the 2016 election. She argues that misogynistic attacks seriously damaged Hillary Clinton’s campaign and that many white women rejected Clinton due, in part, to ‘himpathy.’ Clinton herself has offered support for this idea.

‘Himpathy,’ in this context (read the interview with Manne for a more general and thorough description), is a kind of sympathetic reasoning applied to white male family members who back Trump. She also points to some of the general psychological research showing that, ceteris paribus, people tend to discount women’s expertise relative to men’s. On ‘himpathy,’ Manne cites discussions hosted by Kimberlé Crenshaw and Sumi Cho. They speak with and about white women who appeal to their sons, brothers, husbands, etc. They argue that the empathy white women feel for the white men close to them defeats their prior drive to behave like rational voters.

A Longer Arc

I think Tien’s and Manne’s work doesn’t tell us much about white women in 2016. Tien aims at a broader shift in public opinion that, first, probably isn’t unique to white women (i.e., it’s probably mirrored in white men) and, second, was partially turned back in 2016 (i.e., see the tables above). His data showing high levels of racial resentment among Trump primary voters is entirely compatible with any story about 2016 results, including, of course, my third explanation above (i.e., white women voted for Clinton because they were distancing themselves from the hardcore racists backing Trump).

Manne’s book says a lot about general features of misogyny and misogyny on the job, but specific elections rarely come close to satisfying the ceteris paribus conditions found in empirical studies. It makes any application messy, and the 2016 election was especially messy.

Where I think Tien’s and Manne’s work has great value is their focus on the deeper forces at play. Any story we tell about the voting behavior of white women should probably reference the deeper trend in partisan identification Tien identifies. Racial resentment is probably important to that trend. Any story should likewise reference misogyny. And Kate Manne’s account of misogyny (along with Crenshaw and Cho on gendered race relations) is probably the best philosophical account available.

Another interesting feature of Manne’s discussion is her apparent struggle over whether the white women who vote for Trump are behaving as rational voters. Her discussion of ‘himpathy,’ and the work she cited by Crenshaw and Cho, suggest the answer is “no.” But I think she changes her view on this issue by the end of the book, where she writes that “…a good portion of the dominant social class have a vested interest in maintaining men’s superiority.” To me, that’s the more plausible story.

In that quote, Tien and Manne converge.