Now that we’re into an actual spring, rather than that wave of snow we got in March, let’s take a look at some spring reading!

This month’s list features everything from comedy to sci-fi and radical politics. I hope you enjoy, and let me know what you’ve been reading lately!

Mel Brooks – All About Me!

Mel Brooks finally decided to write an autobiography at well over 90 years old. Why read about the life of a film director who did his best work before I was born? In short, because I loved that work during my high school and college years! Blazing Saddles, History of the World Part 1, Spaceballs, etc.

It’s also worth pointing out that Brook’s generation of Jewish American immigrant families made a giant contribution to U.S. culture and intellectual life. Who could deny Malamud, Asimov, and Chomsky? I wanted to hear what Brooks had to say about this, too.

And I found the book worth a read. Many of the middle chapters slide into trivia from Brooks’ TV and film days, but the beginning and end of the book provide more about his childhood in Brooklyn, his service in World War II, and his final years on Broadway. Those portions make this one well worth checking out.

Charlene A. Carruthers – Unapologetic

Carruthers shares her experience as an organizer in Chicago, notably with the Black Youth Project 100. She brings us this short book on the theory and action of social justice spaces, emphasizing how the fight against intersectional oppression drives the work these orgs do.

I found both positive and negatives in the book, roughly sorting into ‘action’ and ‘theory,’ respectively.

Carruthers provides useful lesson after lesson for organizers from her own experiences. Her description of a transformative accountability process for a young leader accused of sexual assault gives us rich lessons to learn in our own work. And Carruthers speaks well to the promise (though less well to the shortcomings) of Alinskyite community organizing. So, we can learn some things from her ‘Chicago Model.’

However, the theory portion of the book doesn’t add anything. It suffers from core conceptual problems (e.g., calling ‘class’ an identity, defending an Afropessimist conception of racism and a vaguely Maoist conception of activist spaces). The analysis of politics provides insights at times, but at other times it’s well off target. As a result, Carruthers and BYP100 end up advocating politics that oddly swerve between ultra-progressive and radlib territory.

Is the book worth a look? Overall, I think it could be, especially for its discussion of intersectional youth activism. But caveat emptor.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic – I, Human

Chamorro-Prumuzic positions this book as another in a line of books exploring modern ‘AI‘ and its implications. He wants to claim the moderate ground, opposed to both tech utopianism and Luddism.

Does it work? In a way. He discusses both the benefits and drawbacks of technology in our lives. But he never bothers defining ‘AI,’ using it as a catchall term to talk about everything from tech algorithms to social media.

He recites the problems of modern technology in a decent way – from our shortened attention spans to our abuse of social media to bolster our own egos and surround ourselves with people like ourselves. He addresses how AI turns us into more predicable and AI-like people. But he also sees potential in AI. Specifically as a kind of mirror we can hold up to society to detect our own biases.

But the book stumbles over its own feet, often in an ironic way. In a chapter criticizing our tendency to repeat anecdotes and questionable claims, Chamorro-Premuzic himself repeats various anecdotes and questionable claims. Such as his claim that height and affability predict success in presidential elections. This appears to be a false claim he picked up somewhere. And his attempt to distinguish ‘digital narcissists’ (i.e., narcissists who engage in self-promotion without hard work) from ‘altruistic narcissists’ (i.e., narcissists who supposedly benefit the world with their great inventions) has silliness written all over it.

Don’t even get me started on how badly he botches every mention of ‘free will.’

And so, there’s some interesting material here, but the book could use a lot of work.

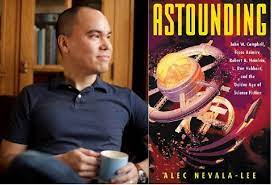

Alec Nevala-Lee – Astounding

This is by far the best book on my list this month. Nevala-Lee gives us a quadruple biography that covers early 20th century U.S. science fiction, counterculture movements, and World War II. He tells us just about all we need to know about the Golden Age of Sci-Fi.

The narrative revolves first around John W. Campbell, editor of Astounding Science Fiction (now called Analog Science Fiction and Fact). And it focuses on three key authors who wrote for Campbell in his early years as editor – Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and L. Ron Hubbard.

For us sci-fi nerds, we know ‘Asimov, Clarke, and Heinlein’ as the ‘Grand Masters’ of the Golden Age. And we’re not wrong. However, Clarke was British, and didn’t really come of age as a part of the immediate Campbell orb. And so, Nevala-Lee focuses on Hubbard, who influenced the early years of Astounding.

That said, Nevala-Lee clearly, clearly doesn’t care for Hubbard, his writing, or the religion he founded. I suspect most readers (and the author) of this blog agree. So, there’s that. In addition, I appreciate how Nevala-Lee contextualizes and explains more deeply some of the things I already knew about the history of sci-fi. Especially the gender issues and social relationships among early authors and fans.

For any reader interested in sci-fi and its history, especially the Golden Age, I suspect they’ll want to pick this one up.