After Bernie Sanders lost to Joe Biden, think pieces rolled off the assembly line. Whence did the Bernie Bros come, and where shall they go hence? Is there a movement bigger than Bernie?

In fact, that’s not quite true. The think pieces didn’t roll off the assembly line. COVID-19 washed most of them from the headlines along with everything else. And so, the U.S. press largely spared us from endless speculation on the future of the Bernie Sanders movement. But COVID also held us back. Leftists should think about this a bit. Where does the Bernie movement go from here? Even this question might assume too much. Is there still a Bernie movement? Or did it die in the couple of weeks after Super Tuesday?

Most electoral campaigns fall apart quickly. I’ve written about some of them: Cathy Glasson in Iowa and Elizabeth Warren nationally. That’s how most campaigns end. Remember the ‘Pete Buttigieg Movement’? Of course you don’t. Neither do I.

Is ‘Sandersism’ any different?

Bigger Than Bernie

Not everyone ignored Bernie Sanders after March 2020. Jacobin had no intention to do so. And so, noted Jacobin authors and Bernie Bros Meagan Day and Micah Uetricht wrote a book on the topic. They called it Bigger Than Bernie, and they published it in the summer of 2020.

Let’s take a look.

Before we begin, here’s something I really like about Bigger Than Bernie. Day and Uetricht apparently sent it to the publisher before they knew the final results of the 2020 primaries. That says something for their approach. It’s a genuine one. They believe there’s a Bernie movement beyond a Bernie campaign.

Jacobin and Friends

Over the last few years, something like a ‘Jacobin line’ coalesced on how to build movements. Here’s how it goes: The U.S. left needs a mass movement to win. Political circumstances leave it with only one good way to build that movement – by supporting electoral campaigns like those of Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020 and using them as recruitment tools. Why? Bernie attracts new and young voters. And he understands that ‘class struggle’ must be a key part of elections.

How does all this work? That’s a bit less clear. But the basic idea seems to be to funnel all those new members and new energy into organizations like the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). They’ll win fights inside and outside the halls of power. Eventually, they’ll build a working class movement that leads us to socialism.

Like any quick summary, this remains incomplete and schematic. It’s also not clear whether or to what extent the ‘Jacobin line’ is unique to Jacobin or even developed primarily by people at Jacobin. The DSA, for instance, articulated much the same line beginning around 2014 or 2015. But Jacobin defends it pretty hard.

Sanders, Class Struggle, and Elections

Bhaskar Sunkara defended the Jacobin line in his recent book The Socialist Manifesto. Day and Uetricht do so as well. And they do it more effectively than Sunkara. Why?

First, they acknowledge some of the problems and tensions. After all, many countries have already tried the social democratic route to socialism they envision. It didn’t work. More troublesome, social democracy tends to tame rather than promote working-class politics. That’s a pretty big problem when social democratic victories are your core mechanism for getting to socialism.

Second, they acknowledge that structuring a movement around elections makes the movement heavily dependent on individual candidates and personalities. What would the DSA do if Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez denounced it? Or lurched to the political right on key issues? Do DSA members love the DSA? Or would they abandon it for Sanders or AOC? I don’t think anyone has a good answer to these questions. Including Day and Uetricht. But at least they put the problem on the table in Bigger Than Bernie.

Day and Uetricht advocate for what they – and others – call ‘class struggle social democracy.’ So far, this is more promissory note than reality. But the basic idea? A socialist political party should build social democratic electoral politics and popular and union agitation at the same time.

For his part, Bernie encouraged some of this during his 2020 campaign. He promoted strike actions across the country. In Iowa, his campaign offered up meeting space for our own local DSA’s Labor group. Sanders was a bit notorious for not allowing local groups to plan his events. But he did effectively partner well with leftist orgs on practical actions.

Movements, Reform, and the Rank-and-File

I find a tension in Bigger Than Bernie between the later chapters and the earlier ones. But I think Day and Uetricht see it, too. On the one hand, they argue for electoral campaigns as the best way to build a leftist mass movement. On the other, they recognize it’s better to have a mass working class movement before running in elections. And so, they endorse elections mostly for pragmatic reasons. We don’t have a movement yet, and we – on Day and Uetricht’s reasoning, as I understand it – don’t have any prospects for building one without elections.

To acknowledge the tension here is to take an important step. But the step may not be sufficient. Indeed, I suspect a prior working class movement might be necessary to build a successful working class electoral coalition. No doubt Day and Uetricht would argue this is too strong a claim. And no doubt I’d respond by citing Fox Piven’s book Poor People’s Movements.

Let’s set this tired debate aside. I find it more interesting that all this explains what went wrong with the Sanders campaign in March 2020. He looked like a winner after Nevada. Then the entire Democratic Party establishment punched him at the same time. He fell. His opponents confused the voters on Medicare for All, and they ran a very effective ‘Biden is electable‘ campaign.

With a working class movement already in place, none of that would work.

Why Social Democracy?

I’d like to part with a question: why social democracy?

In Bigger Than Bernie, Day and Uetricht explore the tension between social democracy and a broader rank-and-file, action-driven working class movement. The former wins power from the inside and the latter from the outside.

But if the latter succeeds, why fully commit to social democracy? We may need to win social democracy in a couple of key areas, like health insurance and housing. But as a full program, social democracy is what Erik Olin Wright called a ‘positive class compromise.’ It ends class politics, not begins them. It’s largely incompatible with rank-and-file class agitation.

In some sense, we all agree on a short-term social democratic program. Especially in health insurance. And, yes, it will probably help some people learn more about socialism and join movements. But surely we must discard social democracy in favor of full public ownership very quickly, lest we end up like German or Swedish social democrats.

Day and Uetricht fault social democracy for its instability. That’s correct after the 1970s. Before then, the problem with social democracy was quite the opposite. It was too stable. Once nations achieve social democracy, they quit working toward socialism. And then the capitalists fight back. Social democracy becomes unstable…in the wrong direction.

The Jacobin Left often points to the Meidner Plan in Sweden as a counter-example. The Plan itself is rather old, but it didn’t gain traction until well into the 1970s. Swedish social democrats adopted the Plan in response to encroaching neoliberalism. They were fighting back against looming threats to social democracy. Neoliberalism, then, jolted them from their slumber. The Plan got little traction under full social democracy.

For people advocating ‘class struggle social democracy,’ the key remains to figure out how American social democracy will be any different.

Postscript: Bernie and I

I appreciated the biography of Bernie Sanders in the first chapter of Bigger Than Bernie. I caucused for Bernie twice in Iowa. But I never learned much about him as a person. I think personality and personal history aren’t all that important to politics. And I suspect Bernie agrees with me on this.

But the biography is good. I didn’t get involved in socialism because of Bernie. In fact, I rolled my eyes when I first heard in 2015 that this confused social democrat from Vermont was going to run for president. I had criticized him for his softness on war as early as 2001. But, in the end, I think I’d learn a lot from Bernie if we sat down and had a chat.

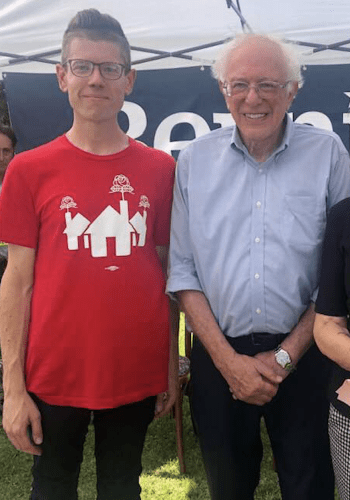

That’s our photo together at the top of this post. Unfortunately, we didn’t have time for anything but a quick ‘hello.’