My readers don’t live under a rock. So, they surely know the Delta variant has given way to Omicron in the last couple of months. At first glance, one might expect this to shake up public debate. Maybe people evolve with the evidence, see things in a new light, and so on.

Well, that didn’t happen. Omicron mostly locked people into their previous biases and hardened their attitudes on the pandemic and public policy. Let’s take a look at how this is working out.

Inevitability and Avoidance

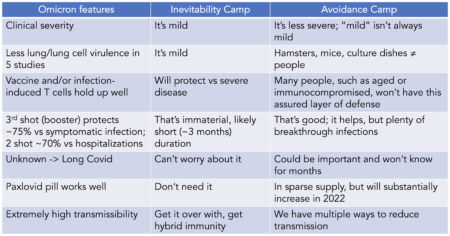

So, here’s a starting point. Eric Topol, a cardiologist and author, presented a graphic on Twitter. The graphic shows what Topol labels as two camps on the Omicron variant of COVID. I think the graphic picks out the camps pretty well.

Here it is.

I think Topol intended this graphic to show inevitability as the ‘bad’ view and avoidance as the ‘good’ view. But I don’t think that quite gets it done.

Against Inevitability

Topol gives us plenty of room to point out the problems with the inevitability camp. He succeeds at that much.

We do need pills and other ways to treat COVID. While long COVID surely isn’t as common as our overly broad definitions suggest, it’s still a big problem and will remain a problem of some kind for years to come. And while vaccinated people have good protection against severe disease without a booster, a booster does help prevent spread. It thereby saves lives. We should keep pushing people to get them.

In short, it’s dangerous to have half a million COVID cases per day. Letting Omicron rip through the country without mitigation of any kind is a bad idea.

For those reasons, the inevitability camp leads to bad public policy. It leads us to drop the kinds of mitigation strategies we need to slow the spread (e.g., mask policies). It leads us to avoid putting resources into treatment.

Against Avoidance

Most readers of this blog already opposed the inevitability camp. But many – especially those who lean to the left, and especially well educated progressives – want to adopt public policy on the model of the avoidance camp.

That’s also a mistake. Here’s why.

First, the evidence doesn’t support the avoidance camp very well, either. It shows that the Omicron variant is milder than earlier variants, and that it’s likely inherently milder and not just milder due to prior immunity. And the vaccines do protect well against severe disease. They protect even people without boosters, and even most older and immunocompromised people.

There’s nothing wrong with being cautious. In fact, many Americans could probably learn better behavior from people in the avoidance camp. People who want to shelter in place – especially immunocompromised people – should do so. But there’s a big gap between saying it’s OK to pursue avoidance as a personal strategy and saying it’s a good public policy strategy.

Avoidance also leads to bad public policy. It leads us to engage in policies where the harms outweigh the benefits.

To use the example at the top of many minds, we shouldn’t close schools on child safety grounds alone. COVID is still far less dangerous to children – even unvaccinated children – than it is to others groups. That hasn’t changed with Omicron. And so, a good mask policy provides enough protection to the vast majority of children.

Plus, we know from the evidence that closing schools is terrible for children. Remote learning failed for most kids. It leaves them up to a grade level behind. And many kids drop out. So, closing schools causes more harm than benefits. And the few benefits go mostly to kids whose parents have time and/or money.

Between Inevitability and Avoidance

It’s hard to tell what public policy should look like. But the graphic from Topol gives us a point of departure. Public policy should hit between inevitability and avoidance.

Omicron likely takes us a step along the way to push COVID from pandemic to endemic status. As it spreads, it will build a lot of immunity, including hybrid immunity among vaccinated people. The inevitability camp gets that much right.

But it also creates dangers along the way. For a short time, more people end up in the hospital. And certain dangers remain to specific groups, especially older people and immunocompromised people (as well as, of course, unvaccinated adults). In most cases, we shouldn’t close schools or other public services. But we should mitigate with mask and vaccine policies. That’s where avoidance gets it right.

That’s the best I can do in terms of public policy. Individual people should do the best thing for their specific cases. And, in general, the best advice for Omicron isn’t new. It’s the same as the best advice for Delta: get a vaccine, wear a mask in public indoor spaces, etc.