The Gaza-Israel conflict is heating up as the Israeli elections approach. And Netanyahu is threatening to annex the West Bank. I’ve been following the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict pretty closely for about a decade and a half, but I rarely post about it.

Why?

There’s no point in beating around the bush. Most writing on the topic is terrible. Politics, religion, and/or ideology lead authors to ignore background conditions, distort historical facts, and misstate even the most basic aspects of the conflict. As a result, writing about the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict is often pointless.

This is all rather polite. What I’m saying is that commentary on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict is full of some of the most untruthful, disingenuous, asinine nonsense imaginable. Many people are simply talking out of their ass.

Not that this wasn’t a fun intro to write.

My aims here are pretty modest. I’ll give a very basic orientation to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Sort of like what I did with North Korea. Who’s involved? What’s it about? I’m not going to do much in the way of offering solutions. That said, I think getting clear about what’s going on is a great start. And it’ll leave most people better off than where they started.

A Book Recommendation

First, a book.

If you’re looking for something on the origins of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, you can’t do much better than Noam Chomsky’s book The Fateful Triangle. What Chomsky gives us is a thoughtful overview of everything happening before the early 1980s, with a focus on the 1960s and 1970s. This is when the conflict really took its modern form.

Chomsky’s thesis provides us with the first lesson on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: it has historically had three major players, not two. Those three are the United States, Israel, and the Palestinians. The US role, at least until the 1990s, was at least as large as that of the Israelis and Palestinians.

The book’s not perfect, and it hasn’t aged extremely well. The US role isn’t as large as it was 30-40 years ago, due in no small part to the modern Israeli economy (a point I’ll return to below). And Chomsky could’ve noted that the Soviet Union was also a significant player, albeit not as large as the other three. But we can cut Chomsky some slack on that. “The Fateful Square” would’ve been an awful book title.

Center-to-Left Perspectives on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Let’s look at some common approaches and what they get right or wrong. First, centrists and liberals. And then leftists and identitarians.

Liberal Perspectives

American liberals usually begin by dividing both Israelis and Palestinians into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ camps. The thought is that the ‘good’ actors (e.g., Israeli Labor Party, possibly Palestinian factions such as Fatah) try to achieve peace. And the ‘bad’ actors (e.g., right-wing Israeli parties like Likud, Palestinian factions like Hamas) oppose peace due to the narrow interests of their faction.

Truth be told, American conservative approaches aren’t much different. Except that they’re more open to Likud and less open to Fatah.

From there, liberals explain the conflict in terms of things like poor communication or religious opposition. They ignore anything that looks like an economic explanation.

Evaluation of Liberal Perspectives

The problem here is that the liberal framing is wrong from top to bottom. Literally everything about it is false.

The Israeli Labor Party, the favorite ‘good actor’ of American liberals, actively opposes peace. And has done so for decades. It led Israel through an invasion of Egypt in 1956 and an invasion of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria in 1967. After seizing the Palestinian Territories in 1967, Labor started many of the illegal settlements that are now a key point of dispute.

To this day, Labor maintains a hawkish stance on security issues. Particularly anything at all relating to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Their candidate for the 2019 Knesset election is a fine example.

Right-wing parties in Israel are further to the right, generally favoring policies in much uglier territory. Netanyahu’s threat to annex the West Bank is a reminder of those ideas. But this is a different of degree, not one of kind.

But What About Oslo?

If you’re looking for a center-left, social democratic political party in Israel that’s not actively hostile to peace, the closest you’ll get is Meretz. And Meretz is hardly perfect. While it’s not an active booster of illegal settlements, it’s not fighting hard to tear them down, either. But Meretz is certainly more sympathetic to Palestinians than any other political party. With the obvious exception of the Arab parties.

Labor and Fatah supported a wide range of ‘peace’ initiatives, many of which you’ve probably read about. This includes things such as the Oslo Accords and the Clinton Parameters. But the real purpose of these events was to undercut more effective peace efforts. Edward Said’s work on Oslo, in particular, is instructive in this regard.

But Isn’t Religion a Factor?

Religion is a factor. And it’s sometimes even important to specific situations or contexts. But while people appeal to religion to justify specific actions, it plays little explanatory role.

You can put Jewish people and Muslim people in a room and have them speak with each other in a civil and supportive manner. And that might do wonders for people’s lives, but it won’t solve the conflict. It’s largely irrelevant to the conflict, except perhaps to various bungled internal debates among Palestinian factions. See, again, Edward Said on these issues.

Leftist and Identitarian Perspectives on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Racial or Settler-Colonial Framing

The American left doesn’t fare much better. The left usually frames the conflict in racial terms. And more recently in settler-colonialist terms.

In large part, this is an attempt to impose an American racial framework on a region where it doesn’t quite fit. The analogies to American racism or South African apartheid are strained. The current situation in Gaza is not entirely unlike a bantustan, but the situation in the West Bank is arguably worse. For practical purposes, the analogy is perhaps rhetorically effective, but it offers little explanatory use.

Israel has taken on some characteristics of a colonial state, especially in its domination of Palestinian politics and social life. And given the Israeli settlements, one might argue this has a settler-colonialist form.

But we do have to mediate these facts with background conditions. One, US domination of the region overshadows Israeli colonialism. The US has been the primary financial sponsor, and it still serves as the primary diplomatic sponsor. The US, for example, vetoes every UN Security Council resolution aimed at peace. Consequently, we might ask whether what’s happening is Israeli colonialism or simply an extension of US imperial policy.

But, two, the founding of Israel is complicated by the very serious problem of Jewish refugees both before and after the Holocaust. The country was carved out of Britain’s Palestine Mandate under non-ideal conditions, to put it mildly.

Economic Frame

And so, here’s where we are. Let’s set aside these very limited frames. What we have is a strong case for an economic frame, perhaps combined with (limited) appeal to settler-colonialism and religious marginalization. Much of the conflict is a conflict over resources, mediated by imperial interests.

What kind of resources?

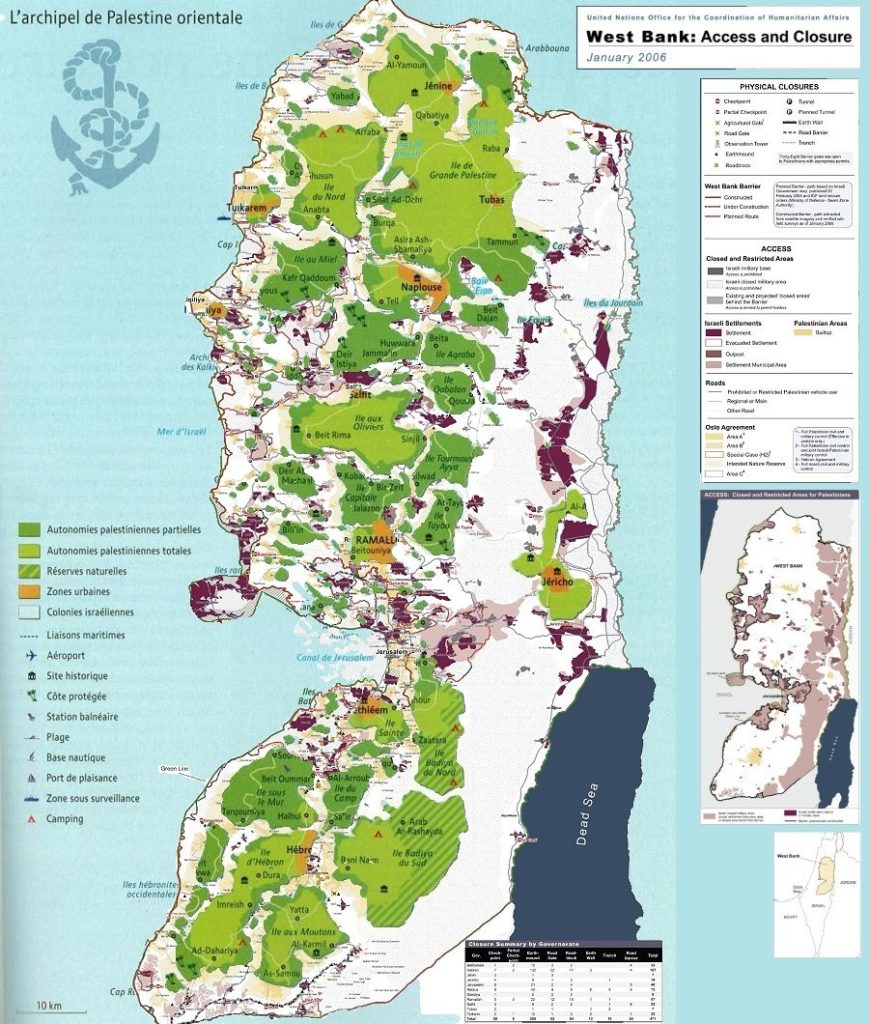

For much of the history here, it’s water and farmland. Ever looked at a map of Israeli settlements in the West Bank? A good map? Israel places them for purposes that are fairly obvious. Those settlements block off access to the Jordan River and to choice West Bank farmland.

During its economic development, Israel depended heavily on these regions. And it had the means to control access to them. Palestine didn’t.

I’m sorry the map is in French. But it’s the best map I could find. The Palestinian areas are in green, mediated by Israeli access points and settlements. Note that Palestinian areas are always separated from important resources by Israeli-controlled zones.

The thing is, Israel is no longer as dependent on these resources as it used to be. As it has developed a modern tech economy, it has given up a small amount of control over strategic regions (e.g., Gaza, though it maintains control over the water supply). And it has allowed a small amount of Palestinian autonomy in others (e.g., the West Bank, with the aforementioned caveat). But Israel does still depend on resources, and also on coerced Palestinian labor. It handles these issues using tools similar to those it used for water and farmland 50 years ago.

The Golan Heights

As a bonus, the economic frame is also highly useful for explaining Israeli control over the western part of the Golan Heights. Israel justifies this occupation in security terms, but that’s too silly to take seriously. While there may have once been some advantage to controlling the region’s geography, technological development makes this unnecessary.

The Golan Heights is rich in oil and water resources. That’s why Israel wants the region. We again find that the economic frame is the best one.

Conclusion: Toward Solutions

Like I said above, I’m not going to say a lot here. I believe what I’ve said is sufficient for getting a basic grasp of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. But this is just getting at the basic historical and material conditions, which are key. A solution isn’t easy, and I don’t think there are any good prospects for one in the near- or mid-term future.

Israel’s tech economy creates a shortage of jobs. This, plus its policies, creates a need for more and more settlers. There’s no peace without a rethinking of settlement. And that probably doesn’t happen without a deep, left-wing transformation of the region.

Toward a real solution, we’d have to think about possibilities like a bi-national, secular state. Or a socialist transformation.