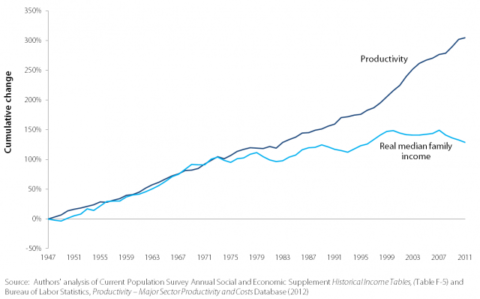

Check out that productivity and income graphic above. Maybe you’ve all seen it before? I think I’ve seen it a billion times and shared it a million times.

At some intuitive level, we know what it means. Capitalism has screwed American workers for at least 4 decades.

But a lot of people miss the point of the graphic. Let’s talk about what it means and does not mean.

Standard Productivity Narrative

There’s a standard narrative on productivity that is, I think, widely accepted. By ‘widely accepted’ I mean that most of the left, and a significant portion of the right, accepts it. To oversimplify, the left jeers it and the right cheers it. But they both, at some level, accept its truth.

The narrative goes something like this:

In a capitalist system, companies and workers both benefit from productivity gains. For most of American history, when workers became more productive, they made more money. Maybe the bosses took a cut. But from 1940 to 1970, in particular, workers won the overwhelming share of money that came from productivity gains. But since 1970, that hasn’t happened. Now companies take all the gains.

Simple enough, right? Workers become more productive, and they share those benefits with the boss. That’s as American as apple pie, baseball, and flags. But, says the narrative, that’s not happening anymore. According to the left, we need to get back to that. According to the right, it’s all fair, because what happens in a free market system is fair. Tough luck.

Problems with the Standard Narrative

There’s just one problem here. It’s wrong. The standard narrative is almost entirely false. It’s simply not true that productivity gains benefit workers in a capitalist system.

In fact, it’s often the opposite. Why?

Marx argued long ago that the accumulation of capital and competition among capitalists leads to both more productivity and stagnating wages. Competition creates larger firms and drives technological innovations that save labor costs (i.e., allow companies to lay off and fire workers).

This is just the broad overview. In addition to wage-reducing competition and labor-reducing technology, neoliberal capitalist firms use Lean production methods, coercive non-compete clauses, part-time labor, and other methods to suppress wage growth. Even when, and even especially when, productivity increases.

From the late 1800s through 2019, this is exactly what’s happened. With the exception, of course, of about 1940 to 1970. Those years are outliers.

During most of capitalist history, to put this into Marxist terms, capitalists increase relative surplus-value by increasing productivity. That is to say that their companies produce more goods with the same amount of labor, thus reducing the value of the goods needed to sustain the working class. And thereby reducing the value of labor power.

These forces allow for the possibility that real wages could rise with productivity. But that’s a mere possibility, and it’s an unlikely one without other accompanying events. Thus, there’s no mystery about what’s happening in 2019. Rather, there’s a mystery about what happened from 1940 to 1970.

What Happened in the US From 1940 to 1970?

1940 to 1970 was a historically strange time in the United States. It was the outlier, not the norm. Workers benefited from productivity gains due to these strange features. Not due to inherent features of capitalism, whether industrial or post-industrial.

First, union density was very high during these years. American workers joined unions in droves. In turn, unions fought hard to carve benefits for their members out of these productivity gains. Not only did they succeed, but union gains also spilled over to non-unionized parts of the workforce.

This means that strong unions are good for everyone. Even workers who aren’t union members.

Second, the United States destroyed most of its industrial competition in World War II. Literally. Here’s what German industry looked like in 1945:

I could show photos of Japan, the UK, or the Soviet Union, but I think you get the point. The US came out of WWII in much better shape than anyone else. Consequently, the US had about a 10-20 year head start in post-WWII industry. By about 1970, Japan recovered. And not just recovered, but thrived.

Advocacy Implications

Misreadings of the productivity graphic (mis)inform advocacy movements. If you accept the standard narrative, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that some fixes to the regulatory system might solve the problem. We just need to clean up the way companies do business. Or clean up the market.

The trouble is, that’s not nearly enough. Winning a larger share of productivity gains requires much deeper activist action. It requires changing the power relations between capital and labor.