‘Class’ is another of those terms we use, but we don’t use it in a standard way. For many of us it boils down to, ‘I know it when I see it.’

I’m going to use Michael J. Roberts’ work (Class: The Anthology) as a framework.

I’ll lay out two approaches and say a bit about why I prefer the second.

Two Approaches to Class

Approach 1: It’s a matter of outcomes. There’s an occupational hierarchy with outcomes that are measurable in terms of things like income, education, and wealth.

Approach 1 comes from a social scientific tradition dating to Max Weber and Emile Durkheim. Income, education, and wealth are indicators of socioeconomic status (SES). This approach is one that treats class as SES.

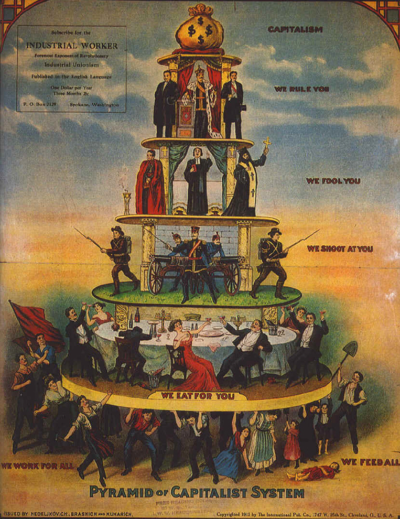

Approach 2: It’s a matter of activity. It is a set of primarily antagonistic relationships between economic groups (e.g., workers and bosses) within labor activity. These relationships reference the ownership and control of resources.

Approach 2 comes from historical materialist and Marxist traditions. It’s more difficult to measure, coming from political economy rather than modern social science.

The choice between these two approaches can be framed as a theoretical or scientific choice, but that’s very limiting. It has far-reaching impact on our political ideas and action. Taking the first approach leads to a flawed understanding of the world.

One mistake that’s easy to make when taking Approach 1 is to treat many bosses and powerful people as working class.

An Example

Suppose we define the ‘working class’ as consisting of people without college degrees. This is pretty common among pundits and social scientists. Usually they treat educational outcome as the leading indicator. The problem is that lots of people without college degrees are powerful economic actors who own or manage businesses.

I know more than one person without a college degree who owns a business that employs 20+ people and has revenue in the millions. They may drive big trucks, drink cheap beer, or live in a rural area, et al. But at the end of the day, they can hire or fire workers. They spend their evenings in very expensive homes.

These are not working class people.

Class and Identity

Another mistake that’s easy to make on Approach 1 is to think of class as another category of identity. This involves treating it as something analogous to gender, race, and sexual orientation. Sometimes people who take Approach 1 even use it as a term within a broader intersectional identity analysis. This leads them to talk about something called ‘classism’. The term is supposed to pick out bias or discrimination against, e.g., low-income people or people without a college degree.

The problem is that it isn’t an identity category and isn’t analogous to race, gender, et al. in the right way. ‘Classism’ is not something analogous to sexism or racism, as argued by, e.g., Abbey Volcano and J Rogue.

The goal of anti-sexist and anti-racist action is to eliminate the barriers that stand in the way of, e.g., black people or women. We eliminate barriers so that they have the full opportunity to succeed as, e.g., black people or women. The goal of class politics, by contrast, is to eliminate the class system. The goal is not to enable people to succeed as working class people.

When anti-racist politics are successful, black people will still be black. The usefulness of racial identities might be in question, but that’s a different issue. By contrast, when class politics are successful, there will no longer be classes at all. And so working class people will no longer be working class at all.

Approach 2, the Marxist approach, allows us to build a narrative that accounts for these asymmetries that are foundational to political theorizing and action.

Marxism and Awareness of Class

However, there are some complications and difficulties with Approach 2.

Some Marxists argue that Marx built into his definition the idea that members are aware of their class status and/or are organized toward pursuing common interests. Sometimes Marxists describe this in terms of a distinction between ‘class in itself’ and ‘class for itself.’ A ‘class in itself’ is a group of people with a common relationship to the means of production, while a ‘class for itself’ is a group of people aware of this common relationship pursuing its interests.

I prefer to leave awareness out of the definition. Awareness is important for collective action, but I don’t think it’s part of what it means for there to be a class. I’ve argued elsewhere that awareness of one’s status as a member of a group can affect one in a wide variety of ways. These ways are fairly complicated, and unnecessarily cloud the definition.

Postscript

This is post #4 in my series on political foundations. You can find the other three posts in this series by clicking the ‘Foundations’ category tag below.