Through Commune magazine – by way of our local tenants union – I recently heard about Woodbine. It’s a space in Queens for food aid in the coronavirus era. Among other things, the Commune article discusses the rent strike, that object of lots of recent fascination.

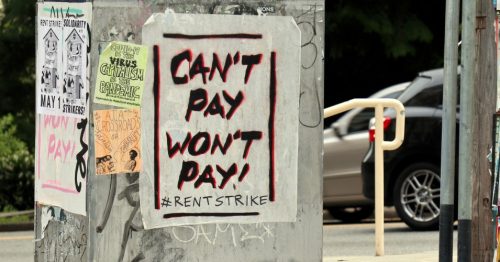

As Commune puts it, the slogan of the nascent New York rent strike is ‘can’t pay, won’t pay.’ People in Iowa City talk about the same thing, often with the same slogan. So, what’s happening here? Is it a good time for a rent strike? If so, is it best to organize a rent strike around inability to pay rent during hard times?

What is a Rent Strike?

A rent strike isn’t just when someone – or a few people – decide not to pay rent. Rather, it’s a collective action built through collective organizing. One person refusing to pay rent – or a few people refusing to pay rent – is just rent withholding, and it almost always ends badly for the tenant(s). Ending badly could come in the form of late fees, a collections agency, et al.

Collective action constitutes but one component. That’s the way any change happens. The second thing about a rent strike? Tenants organize it around particular demands. Maybe the landlord refuses to fix a bug infestation in a 20-person building. Tenants demand the landlord fix the problem. Maybe the landlord wants to raise the rent. Tenants demand the landlord keep it the same or lower it. Withholding of rent isn’t an open-ended threat or a necessity. It’s a tool for forcing the landlord to meet the demand.

Finally, it’s not merely a matter of having more than one tenant involved in the action. A successful rent strike involves figuring out how many people are impacted by the issue and then organizing a majority – probably a super-majority – of the tenants. If the demand impacts all tenants in a 20-person building, the landlord could probably ignore 3 or 4 of them. But 14-15+ tenants on a rent strike stand a much better chance of winning.

What’s Required?

Usually several steps come before a rent strike. Organizing tenants begins with awareness and trust. And this mostly comes in the form of one-on-one conversations, group discussion, and collective struggle via escalating actions.

With the Iowa City Tenants Union, we go door-to-door talking with tenants about their housing situation. Or at least we did prior to coronavirus. These days we do it online. The best way to do it is to ask fellow tenants open-ended questions about the issues they’re facing. ‘How are things in your building?’ ‘What kind of job is your landlord doing?’ ‘What would you like to see fixed/different?’

Most tenants have problems or issues of some kind. We typically turn the conversation toward collective action as a way to solve problems: inviting the tenant to the next meeting, putting more people in the room (also now online), helping people draw connections between issues. Over time, we solve problems and build trust, addressing issues like security deposit theft, mold problems, bug problems, et al.

The Infrastructure of a Rent Strike

It’s this trust that’s more essential than anything else to a rent strike. Why? A rent strike is a high risk action. If it fails, the tenant might get evicted. And even if they don’t get evicted, they might owe late fees or attorney fees.

Even without the financial impact, a rent strike is scary. The landlord can and will employ intimidation and threats. Most people don’t like confronting all this. Much like most people don’t like confronting their boss. Tenants need to know there’s a plan in place and that their fellow tenants will stand with them in the face of these threats.

These things are why rent strikes can’t be thrown together at the last minute with just a few people.

‘Can’t Pay’ or ‘Won’t Pay’?

This should make it clear why movements put together at the last minute without a critical mass of tenants from the same landlord – under the slogan of ‘can’t pay, won’t pay’ – won’t work as a rent strike. The tenants have to build trust before knowing their fellow tenants will stand with them.

What it might be successful at doing, though, is marshaling collective outrage. Collective outrage has its place in leftist movements, and it’s an important place. But it’s not a rent strike. As someone organizing fellow tenants, I think collective outrage has its place at the awareness-building stage. The next step is to put in place the infrastructure – the one-on-one conversations, trust-building, escalating actions – needed to run a good rent strike.

A good rent strike goes by a different slogan: can pay, won’t pay. It’s a conscious, collective withholding of rent one could’ve paid, but decided not to in order to get the demand met. Over time, demands can grow. Eventually those demands can transform into collective political demands around tenants organized as a class, e.g., public housing.

Without the infrastructure for a rent strike in place, the best way to handle sudden loss of income and inability to pay rent is to apply for local assistance programs, ask the landlord for more time to pay, et al. And work on collective organizing so that better solutions will be in place as soon as possible.

Commune

The sin of the framing in the Commune article, then, is the conflation of emergency response with the careful and deliberate planning of goals and methods for reaching those goals. This is a common issue with folks on the left.

There’s a second problem. Among other things, COVID-19 accelerated already troubling trends: the setting aside of one-on-one conversations and gradual building of power in favor of trying to take shortcuts to activism via memes, social media, and the seemingly radical – though mostly just lazy – call for a ‘general strike.’

If the goal of any of this is to succeed rather than to make oneself feel like one is succeeding, then it’s a remarkably unsuccessful strategy. It doesn’t work. It’ll never work. There are no shortcuts to good organizing work, as Jane McAlevey would put it.

The Goal of Tenant Organizing

While there are many goals of tenant organizing, I think there’s one overarching goal: building collective tenant power, forming tenants as a class, and then transforming housing from a privately held investment to a collective, democratic, public resource. No one should have to pay a person or a company for the place where they live.