Source: https://www.britannica.com/topic/fasces/media/202174/223607

I’ve been sitting for awhile on the question of whether Trumpism is a fascist movement. Are we moving toward fascism in the United States?

It’s a big question, and it’s gotten lots of passionate responses. But I find a lot of the responses ill-informed or otherwise misguided. I also find that it’s a complicated question. Generally, I try to keep these posts to around 1500-2000 words. And to a focused topic. On the issue of fascism, however, I found this to be a burden.

So this is the first post I’ll write on the topic. I’ll add a second, and possibly a third, later. I’ll start by clearing some ground.

What, exactly, is fascism?

Against Checklists

Some people approach fascism the way doctors diagnose a disorder. First, they lay down a definition. Second, they put it into practice by creating a checklist of features of fascist states. Finally, they tick the appropriate boxes for the state in question and consult an interpretation.

Kinda like that quiz a posted awhile back, but kinda not.

But, here’s the thing. Fascism isn’t like Antisocial Personality Disorder. ‘Fascism’ is a fuzzy term without a clear definition. It doesn’t have diagnostic criteria. It’s like nothing you’ll find in the DSM.

I don’t mean this in any flippant sense. I’m making a methodological point. Umberto Eco’s account of fascism is an example of this mistake. Eco lists 14 properties of fascist states. Stanley Paine, a historian of fascism, clocks in with a 13-point checklist. For Emilio Gentile, it’s a 10-point checklist.

As general political diagnostic tools, these may have their uses. A government that has a lot of these features is a bad one. But they’re too broad to use as analytical tools to study fascism. If you read any of these checklists, lots of non-fascist states tick a lot of boxes. When you try to use the tools to get at fascism, specifically, you end up writing bad articles.

To get more specific, we need to get down into the kinds of historical situations where fascism arises.

Exemplar Countries

So much for checklists. Here’s a different starting point. Let’s look at some countries that we know were fascist in specific time periods. I’m going to do this by fiat. I’ll simply declare that some countries were fascist during specific periods. If you disagree, that’s fine. You can run the same exercise with a different list.

Here’s my list of clearly fascist countries and their time periods:

Italy (1922-1943)

Japan (1931-1945)

Germany (1933-1945)

Portugal (1933-1974)

Spain (1939-1975)

I take it there aren’t any major surprises here. Italy literally coined the term ‘fascism.’ And Germany is on everyone’s list. Japanese fascism, or ‘Shōwa Statism,’ was the product of nationalism, imperialism, and anti-communism. Portuguese fascism, the Estado Novo, arose from instability after the fall of the monarchy. It also came under the influence of Italian anti-communism.

I’ll emphasize at this point that this list isn’t exhaustive. There are other countries that, in my view, went through fascist phases. I’ll talk about a few below. But the five countries above are the fascist states on any serious list.

Common Background of Fascist States

Ideally, we’d do two things here. First, we’d identify what the five fascist states above had in common. Did they have a similar political status? What were the historical conditions under which they all arose? What sorts of things did they all do? Second, we’d ask which features are unique to fascist states. What do these fascist states have in common that non-fascist states don’t have?

If we did that, we’d have it: a clear account of fascism that we can use to judge today’s states.

The thing is, we probably can’t do both of these things. The first we can do, and I’ll try to do it below. The second, though, is tough. Uniqueness is fleeting. There are a lot of regimes out there, and just about anything that all fascist states have done have also been done by some non-fascist states. Moreover, we’ll find that some of the conditions that produce fascism also produce non-fascist states.

What I’ll do is lay out a list, with a strong focus on the historical conditions at play. Here’s the list of common features I find between the five countries I listed above:

1. Peripheral Capitalist Status

None of the countries were superpowers. They weren’t the British Empire. They weren’t the United States or the Soviet Union during the middle of the 20th century. All of these countries leaned, to some degree or another, toward the margins of power in the capitalist system. Japanese leaders, in particular, were miffed by Western leaders who dismissed Japan’s claim to greater status and power.

For what it’s worth, Antonio Gramsci found this to be of particular interest in the development of Italian Fascism.

2. Economic Crisis

Each country on the list was in, or shortly past, a major economic crisis. It’s hardly a coincidence that four of the five countries went fascist within a decade after the beginning of the Great Depression. The fifth country, Italy, had heavy economic and social instability caused in no small part by its debt crisis after World War I.

3. Political Crisis

I mentioned above the instability in Portugal following the end of its monarchy. Italy and Germany toggled frequently between governing coalitions and had heavy political gridlock prior to their fascist turns. Japan had serious conflicts between an imperial military and reluctant politicians.

4. Short Democratic Histories

Italy and Germany literally didn’t become unified nation-states until the 1870s, only 50-60 years before their fascist turns. Their historical experiments with democracy were even shorter. Democratic reforms in Japan date largely to the Taishō period, which started only about 20 years prior to its fascist turn. Portugal, again, had just emerged from monarchy. Spain’s Second Republic was less than 10 years old in 1939.

5. Left-Wing, Existential Threats to Capitalism

Given the overall theme of this blog, you might think I’ll make a big deal out of this one. And you’re right. I will. It’s not just that these countries were going through economic and political crises. There were real, left-wing, existential threats to the capitalist system at play. The October Revolution that led to the Soviet Union had happened not long before. Each country on this list was worried about the Soviet Union.

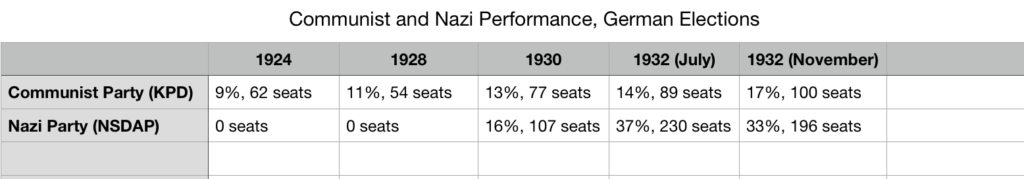

Each of these countries had reasons to believe that communism was knocking at its door. In Spain, anarchists were literally running an entire region of the country, and fascists responded to the crisis of capitalism by invading. In Germany, look at the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) as compared to the Nazi Party (NSDAP).

German Federal Elections, 1924-1932.

The KPD increased its vote count in every German election over the 8 year period. Even the one after Hitler was first elected in July 1932. Continued KPD gains, against Nazi setbacks in November 1932, played a clear role in many of the tragic events in Germany starting in 1933.

A Note: Things Not on This List

I’ve focused on the historical conditions of fascism. And so, for obvious reasons, things like stealing elections, fake elections, show trials, etc. aren’t on the list. But you might have expected to see things on this list such as leader cults, reverence for tradition, imperialist expansionism, antisemitism, etc.

The reason none of those things are on the list is simple enough. Those things were very important to one, or more than one, fascist state. But not to all of them. And that’s the key difference. Expansionism, for example, was central to Italian, German, and Japanese fascism. But not so much to the Portuguese or Spanish variety. I think you’ll find a similar story with the other things I list above.

Additional Examples of Fascism

I want to clarify a certain point here. Some of you might be thinking that I’m going to isolate fascism to the 1920s and 1930s.

Sometimes people try to isolate fascism to a specific time period to argue that countries in 2018 simply can’t be fascist. But I’m not doing this. In fact, I think that fascism continues to be a problem whenever and wherever the historical conditions I list above re-emerge.

The 1920s and 1930s give us the clearest examples of fascism because of the combination of economic and political crises with left-wing threats to capitalism. But that combination can, and has, occurred at different times.

For a list of fascist states that developed after 1940, I’d start with this list:

Iran (1953-1955)

Guatemala (1954-1986, possibly also 1930-1944)

Chile (1973-1990)

This list is no doubt incomplete. But in each case above, we find the requisite background political and economic crises, the existence of a genuine left-wing threat to capitalism, and a fascist period of varying lengths. Iran, which had the shortest time period and is probably the most controversial inclusion, was fascist for only about two years because its monarch (the Shah) kept the fascists on a short leash. The Shah got rid of fascism when it was no longer needed to ‘save’ the political and economic system from its crisis.

Looking at the world today, where are conditions ripe for fascism? Many of the obvious examples are in South America. Brazil’s recent election is a concern, and Bolivia and Venezuela are also at great risk. These are places where I find most or all of the historical conditions that lead to fascism.

So, What is Fascism?

With this all in place, I’ll offer a provisional account of fascism. My account here is, you might say, functional and descriptive. I’m trying to get at the role fascism plays and the conditions under which it arises:

Fascism is the emergency management mode of capitalism. It arises during times of serious crises and left-wing threats in order to save capitalism from itself.

In terms of class analysis, it’s a movement led by petty bourgeois elements and interests with some proletarian and/or lumpenproletarian support and enforcement. However, conservative movements in general gain much of their support from the petty bourgeoisie. The difference between conservatism and fascism is the existence of crises, the rise of a left-wing threat to capitalism, and the frantic, emergency nature of the movement as seen through mass violence outside the typical institutional structures.

Writers who have best addressed the nature and dangers of fascism include Gramsci, who I noted above, and Leon Trotsky.

Next Steps

The next step is to apply this account to the United States in 2018. I’ll do that in a second post.